How World in Motion heralded England's leap out of the dark ages

- Published

It is 30 years since New Order's World in Motion topped the charts. Set against a backdrop of hooliganism, political threats to withdraw from Italia 90 and a newspaper circulation war, how does the song symbolise the England football team being dragged out of the dark ages?

A waterside mansion straddles a river in the picturesque Berkshire countryside.

Once a watermill, the grand setting would seemingly be an elegant retreat for a genteel getaway.

But in a studio which had once belonged to Led Zeppelin hell-raiser Jimmy Page, it was perhaps no surprise a gathering of party-mad musicians and fun-loving footballers would soon shatter the serenity.

"We were caning it," bassist Peter Hook announces jocularly as he recalls the frenzied recording session for the England team's official World Cup anthem.

"It got very ribald. Tony [Wilson, Factory Records' boss] turned up with a huge bag of suspect stuff and then it slowly went downhill. It sort of plateaued a little bit when the players arrived to sing, but then accelerated because everybody started drinking.

"Literally, it was like herding cats. Midway through the session they all just upped and left. When we were going 'What's up, what's the matter?', they said 'We've gotta go. We're opening a Topman in Middlesbrough!'"

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Wilson had initially been approached via a telephone call from the Football Association's chief press officer David Bloomfield, but the partnership with the FA would not be an easy one. Inter-band relations were also strained.

Awkward squad sing-a-longs had previously characterised the sport's dalliances with the pop charts, but World in Motion took its cues from the electronic rhythms the band had championed through the 1980s and the ecstasy-driven club culture taking hold of dancefloors across the country.

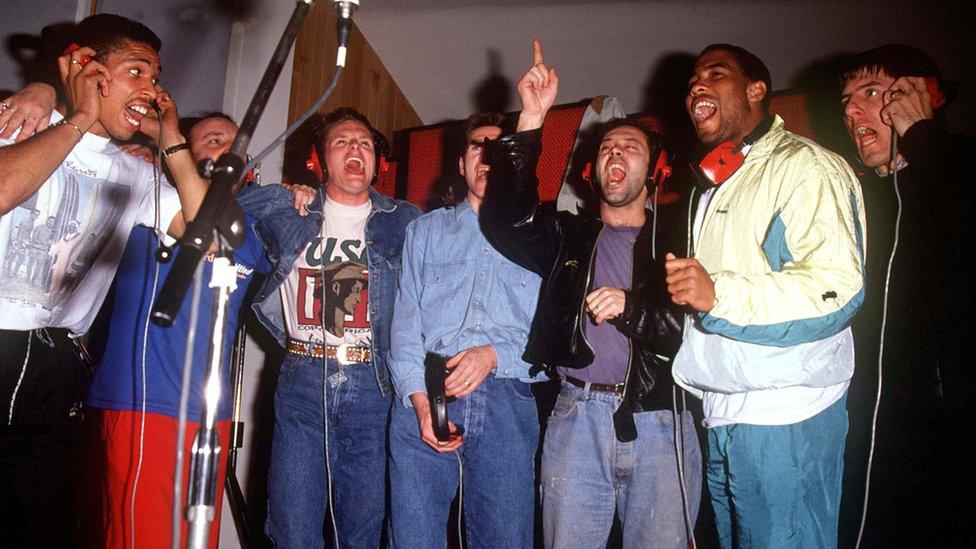

New Order worked up the remnants of an existing track, enlisting actor, football fan and party animal Keith Allen to help write the lyrics. Its "rushed" recording would see only a handful of the England squad arrive at the studio - each paid via cash-filled brown envelopes handed out by Wilson.

The challenge appealed to the band's "sadistic nature," Hook jokes, recounting how they watched Paul Gascoigne "drink three bottles of Champagne from the neck of the bottle".

"In a funny way, it actually brought us together because we hadn't had a great time doing [1989 album] Technique. We were basically splitting up and we came back together to do World in Motion.

"The FA weren't 100% behind it, I have to say. I think we were used to being fawned over and not being treated like an unwelcome guest. We never got any tickets [to the World Cup] or any memorabilia.

"I think it was Keith who came up with the idea of the rap. My memory of it is he did help Barney [Sumner, New Order vocalist] in the same way we all helped Barney. There were a few, shall we say, clandestine meetings between the two of them in dark corners and the rustling of notes etc.

"It wasn't the easiest of sessions, but the footballers gave us a welcome distraction. We didn't get everything that we needed so we asked them to come again. They refused because they didn't have the time or whatever so we ended up finishing the vocals ourselves."

Only a handful of players turned up for the recording session

That any of the squad at all had been involved was largely down to Jon Smith, the side's commercial representative. Influenced by what he had seen in the United States, he had worked to increase the number of corporate tie-ups - overseeing a £1m "players' pool" thanks to deals with the likes of Coca Cola and Mars.

Embarrassed by the "horrible" All the Way, which had trundled off the Stock Aitken Waterman production line to accompany England's disastrous Euro 88 capitulation, he was adamant an Italia 90 track would provide atonement.

The team's leading striker Gary Lineker was for once not onside. Describing football songs as "a bit twee", he was no more enthused when New Order were brought on board.

"We worked to create this song, which I loved, then I had to get the team onside," says Smith, who acted on behalf of Argentine superstar Diego Maradona across a four-year period in the late 80s and early 90s.

"One by one I phoned them up and I'd got about half the squad, but, you know, Lineker's voice was very loud, as were a couple of others, but my breakthrough was getting John Barnes.

"Digger [Barnes's nickname] said 'I love it, I love the feel of it'. His voice was just as loud as Gary's and so we finally got them to agree.

"Fortunately, the video was so strong with Barnes that it just worked. It was a cleverly crafted piece of music and then it had the choral bit, with 'We're singing for England, En-ger-land', but couched in very 'now' musical terms."

The track was released on 21 May 1990 and entered the charts at No 2. It claimed the top spot on 3 June, dethroning Adamski's Killer. Eight days later England kicked off their World Cup campaign in Cagliari.

Police in riot gear were a common sight at England games through the 1980s

At the turn of the decade, English football was associated with tragedy and hooliganism.

In all, almost 200 people had died in stadium disasters at Bradford, Hillsborough and Heysel, with the nation's club sides banned from European competition in the wake of violence by Liverpool fans in Belgium.

As Italia 90 approached, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's government even mooted the idea of withdrawing the country from the World Cup over fears it would provide a "natural focus" for hooliganism.

"The 80s for English football were truly dismal," says Pete Davies, who documented the side's Italian World Cup adventure in his eyewitness account All Played Out - adapted into the 2010 documentary film One Night in Turin.

"Stadiums were crumbling urinals. They were dangerous. It was not safe to go to matches and it had become a ridiculous cartoon to see all English fans as hooligans."

Furthermore, despite a lengthy unbeaten run heading into the tournament, the side's ability - and the competence of manager Bobby Robson - was repeatedly called into question by a baying press pack.

A tense 0-0 draw in Poland - England were saved by the crossbar in the final minute - sealed their berth in Italy, but for the media mob the performance left much to be desired.

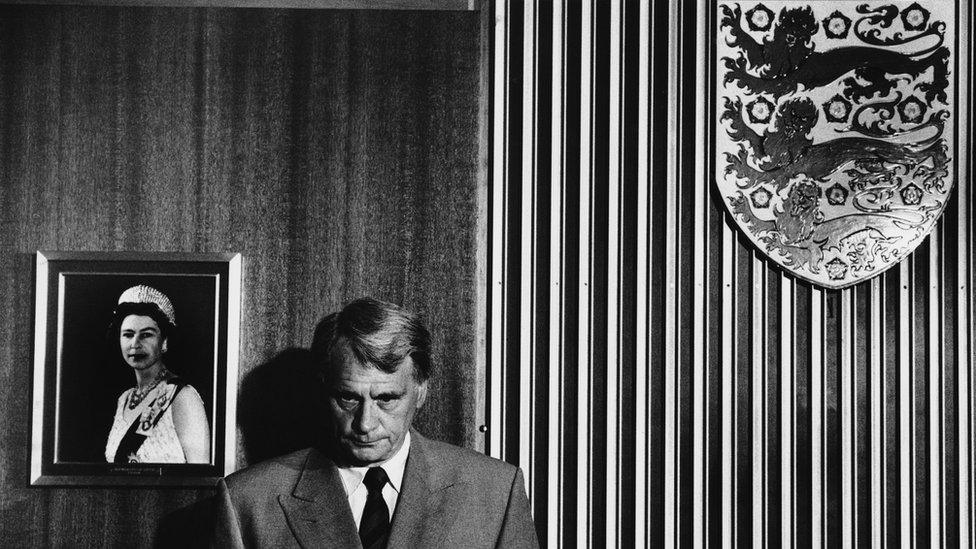

One tabloid denounced the side as "donkeys", with Robson later labelled a "traitor" and "bungler Bobby" when it emerged he would join Dutch side PSV Eindhoven after the tournament.

On 24 May 1990, a glum-looking Bobby Robson announced he would be leaving his role after the World Cup

The squad arrived in Italy amid "an absolutely toxic cloud of enmity, bitterness and resentment between themselves and the media," says Davies, who enjoyed an extraordinary level of access to England's manager and players ahead of and throughout the tournament.

Their style of play was seen to be "clumsy and oafish... like that of medieval yeomen".

"At that time, millions and millions of people bought The Sun or The Mirror. The circulation war between the tabloids was incredibly intense, and the back pages drove it, so football reporting was off the chart in terms of the stuff that was invented and how the tiniest thing got blown up into gigantic storms.

"There was a really unpleasant atmosphere around what some of the journalists would get up to and how fed up and exasperated the England players were.

"The same element of the media was also demonising England fans in league with the government. Supporters in Italy were so utterly unrepresented by our own government."

A woeful opening clash against the Republic of Ireland seemingly justified the media negativity, but Robson and his squad found redemption in four remarkable weeks that transformed the cultural landscape.

A marauding Gascoigne, who secured his place in the 22-man party only six weeks before the competition, was the team's star man as England made their way to the semi-finals. World Cup foes West Germany awaited.

"We were told to go home after the first match. Well, I believe the country back home is dancing in the streets now," said a jubilant manager after the narrow quarter-final win against Cameroon's Indomitable Lions.

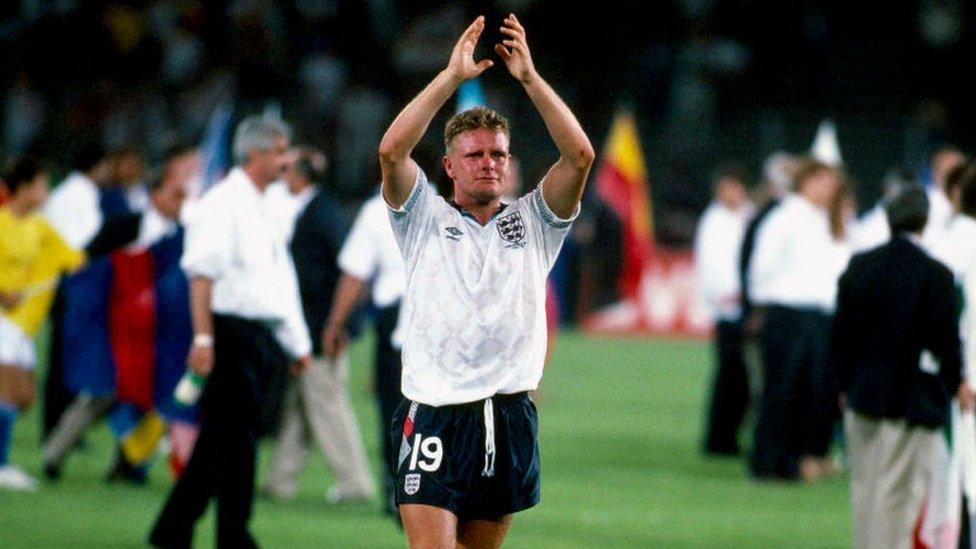

Paul Gascoigne was overcome at missing out on the World Cup final

Days later, more than 26 million UK television viewers watched helplessly as the side's valiant efforts foundered under the floodlights of Turin's Stadio delle Alpi stadium.

Gascoigne, just 23, famously broke down in tears after a booking that would have barred him from the final, and England suffered penalty shoot-out heartbreak for the first time as Chris Waddle fired his spot-kick high into the night sky.

There was to be no repeat of the triumph of 1966. England's World Cup campaign had failed again.

World in Motion had not.

"In its own small way, that piece of music was probably the forerunner of all the good that became English football in the 90s and 2000s," says Smith, who would be an instrumental figure in the launch of the Premier League in 1992.

"All I can say is it's bloody good and it makes you smile. How can you go wrong with New Order?" says Davies.

"The tournament unfolded as if something very special and extraordinary was happening. By the semi-final, it really was rocket-to-the-moon stuff. The thing had taken on an energy of its own. It was accelerating. You just went with it.

"In many regards, Italia 90 was an absolutely pivotal turning point. It was incredibly important for English football and incredibly important for anyone in England who loves football. It changed the perception of English fans.

"Gazza was a revelation - the story of the tournament. When he cried, it was a crucial element in humanising the game, in making the game loveable again, bringing passion back.

"After that, you knew things were changing. Football wasn't a swamp of hooliganism as it was before. It was back as a source of joy and not an object of shame and derision."

- Published13 May 2020

- Published11 July 2018

- Attribution

- Published10 June 2018

- Attribution

- Published28 April 2018

- Published29 May 2015