1984 miners' strike: Retired policemen recall pitched battles

- Published

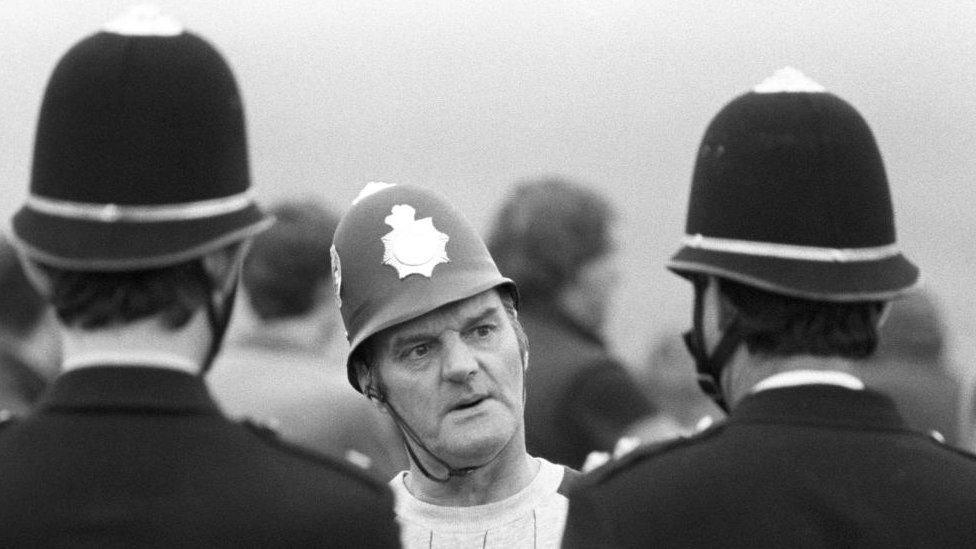

A striking miner wearing a toy police helmet faces policemen at Gascoigne Wood drift mine near Selby, North Yorkshire, during the 1984 miners' strike

The words coal mines and the eastern counties could rarely have been found in the same sentence.

A glance at a Northern Mine Research Society map of coal mining in the British Isles, external makes the picture clear.

Mining areas are marked in red and other areas in green: a swathe of green covers Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Cambridgeshire, Norfolk, Northamptonshire, Suffolk and Essex.

But 40 years ago, hundreds of policemen from the East of England played their part in one of the defining coal mining events in British history; the 1984 miners' strike.

Arthur Scargill, general secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), at the 1984 TUC conference in Brighton

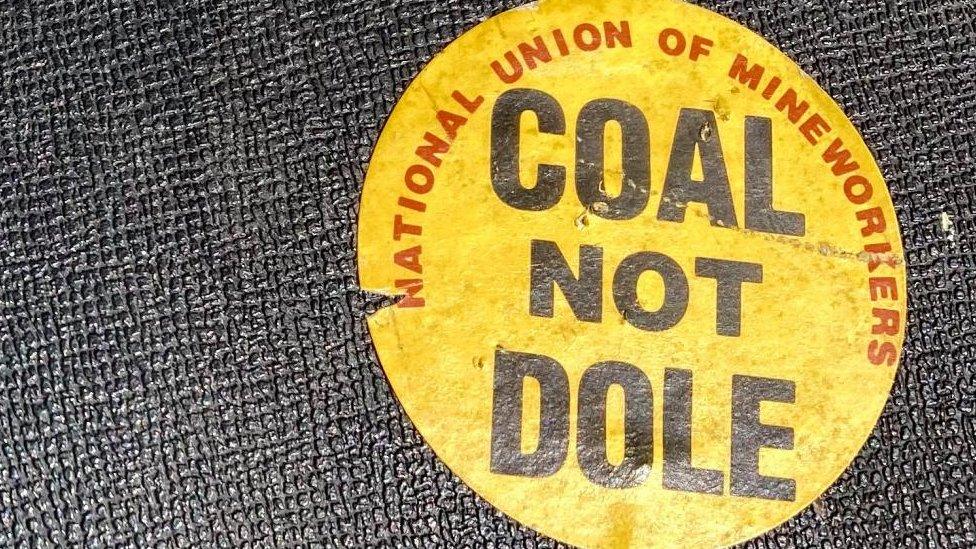

Miners had walked out in March 1984 - in a bid to stop Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, external's Conservative government closing pits - and they stayed out for 12 months.

Police forces in mining areas such as Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, trying to ensure miners who wanted to work were not stopped by pickets, struggled to cope.

Huge numbers of policemen - but not policewomen - were drafted in across the country with a national reporting centre set up to co-ordinate operations.

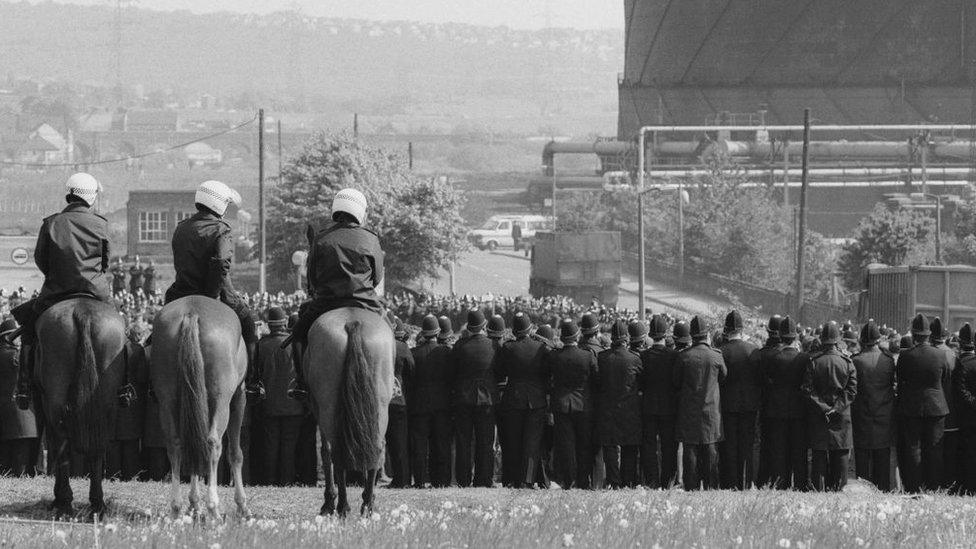

Police in Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire needed help from other forces during the 1984 miners' strike

Some forces in the East of England were better prepared than others.

Bedfordshire had a special unit to deal with public disorder, with officers trained in riot control at a disused brick works near Bedford and in old aircraft hangars at Cardington.

Retired officers recall how Hertfordshire police did not have enough suitable vans to ferry officers north, so instead had to make do with hiring vehicles from a gardening firm.

Eastern counties policemen were on duty during some of the most violent confrontations with pickets.

Some made their first trip down a coal mine - and came to respect the miners, and sympathise with their plight.

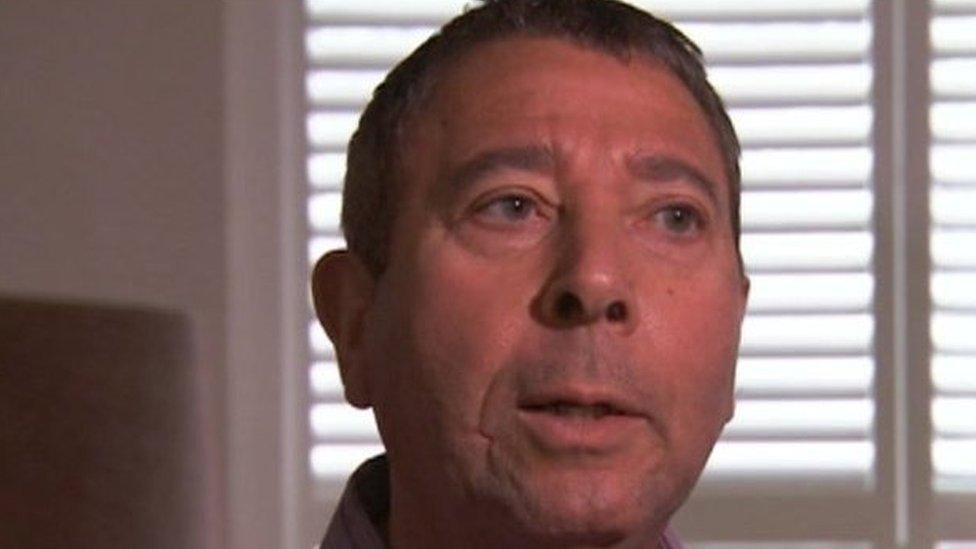

Some police have said they sympathised with the plight of striking miners and gave their wives and children food

Ex-soldier Bill King was a Bedfordshire chief inspector in 1984 and led a unit of officers specially trained to deal with public disorder.

He told the BBC his officers stood alongside colleagues from Norfolk and Lincolnshire during clashes at a South Yorkshire pit that became known as the "Battle of Hatfield Main".

The former Grenadier Guard, 80, had previously been involved in peacekeeping duties in Cyprus following disputes between Turkey and Greece in the mid 1960s.

"It was the same kind of situation in Hatfield, standing in the middle of the road in front of 150 pickets," he said.

Mr King said he had witnessed many things during a 30-year police career but the miners' strike stood out - particularly the week at Hatfield Main Colliery, external in November 1984.

"Duty during the day usually consisted of long periods of waiting, or travelling, or talking to the pickets, interspersed with short periods of violence or pushing and shoving with the pickets," he said.

"The exception was that week at Hatfield. I remember the sheer torrent of stones raining down - the sky just fell on us with stones, sticks, bits of railings, bricks, ball bearings.

"At one point I looked up and the sky was black with missiles."

A Brief History of the 1984 Miners' Strike

The strike was an attempt by miners to stop the National Coal Board and Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher closing coal mines across Britain.

By the early 1980s, mines were losing money and the number of people working in them was falling.

On 6 March 1984, the government announced the closure of 20 coal mines making 20,000 miners redundant.

The strike began in Yorkshire, when miners at Cortonwood mine walked out following a local vote.

On 12 March 1984 Arthur Scargill, head of the National Union of Mineworkers, announced a national strike.

The strike officially ended nearly a year later on 3 March 1985.

Striking miners returned to work and many mines were closed during the following years.

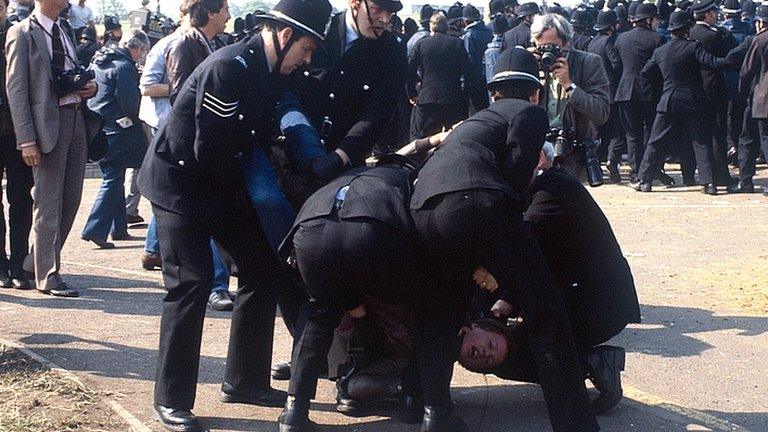

Pickets and police outside Orgreave coking plant in South Yorkshire during the 1984 miners' strike

Some of the worst clashes between pickets and police were at a coking plant at Orgreave, South Yorkshire, in June 1984.

Striking miners wanted to stop lorries carrying coke to fuel the Scunthorpe steel furnaces and 10,000 striking miners clashed with about 5,000 police.

'Terrified'

Hertfordshire police were on duty at the plant - Tony Munday, now 70, was there as a police constable.

"There were thousands of people, thousands, it was unprecedented," he said.

Tony Munday was on duty with Hertfordshire Police at the Battle of Orgreave in June 1984

"All we had was the custodian helmets - peaked hats - no protective equipment, no shields. There was a hell of a lot of bricks and other things being thrown in our direction.

"I just tried to keep looking down at the ground because I was terrified of being blinded."

There have been calls for an inquiry into the actions of police at Orgreave.

Scores of miners were arrested, and many injured, although all charges were later dropped.

The Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign, external held a protest in Sheffield in December 2023.

Mr Munday has backed calls for an inquiry into how police handled the aftermath of Orgreave and claimed he was told by senior officers what he should write in his statement following the clashes.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher led the Conservative Government during the 1984 miners' strike

Retired officers said they would normally leave home on a Sunday and spend a week policing the strike before going back to normal duties for a period, then heading north again.

That pattern continued for many throughout 1984.

Ex-policemen said policewomen were not sent to strike areas but stayed behind and covered gaps left by colleagues.

Police stayed in various types of temporary accommodation during the 1984 miners' strike

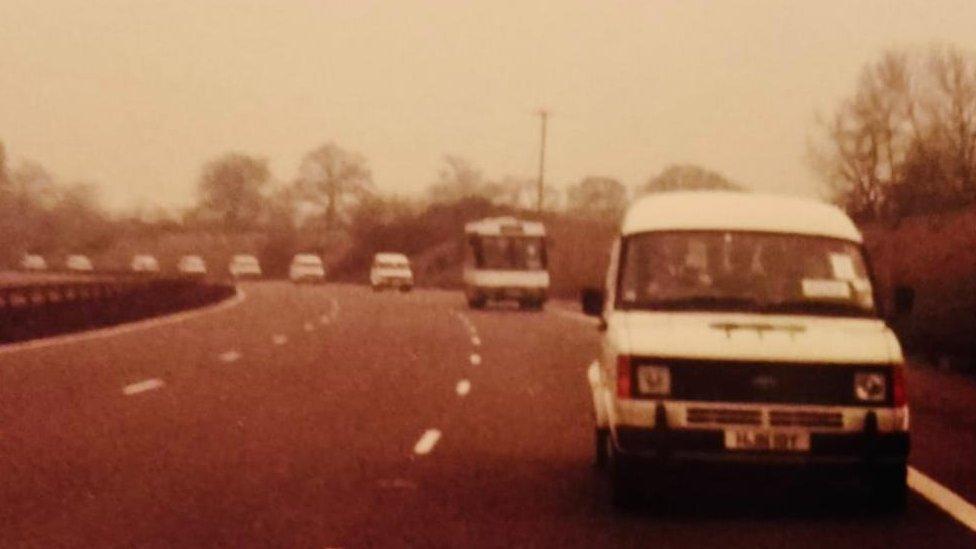

One retired Hertfordshire officer, who did not want to be named, said his force hired vans from a gardening firm.

"Hertfordshire didn't have enough of the right type of vehicles to get people to Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire," he said.

"So they hired vans. I remember the vans had a tree motif on which looked like a lollipop. It caused a bit of amusement when we arrived.

"The only advantage was that these vans had cassette players in, whereas police vans didn't. Everyone turned up with their own cassettes and there'd be debates about what we listened to on the way."

Hertfordshire police hired vans to carry policemen north during the 1984 miners' strike

Derek Crosby, 66, was a PC in Hertfordshire during the strike and later worked in a civilian role for Cambridgeshire police.

He recalls working in various parts of Nottinghamshire - at collieries, including Harworth, and on roadblocks trying to stop "flying pickets" travelling into the county from other areas.

Mr Crosby recalled at one point during the strike being taken down a pit by Nottinghamshire miners.

He remembered being in a tunnel miles underground and hearing wooden pit props "creaking".

"I did not like it," he said.

"I had lots of empathy for the miners' cause."

Follow East of England news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk , externalor WhatsApp 0800 169 1830

Related topics

- Published1 March 2024

- Published17 June 2014

- Published13 September 2012