Cambridge study reveals Britain industrialised earlier than thought

- Published

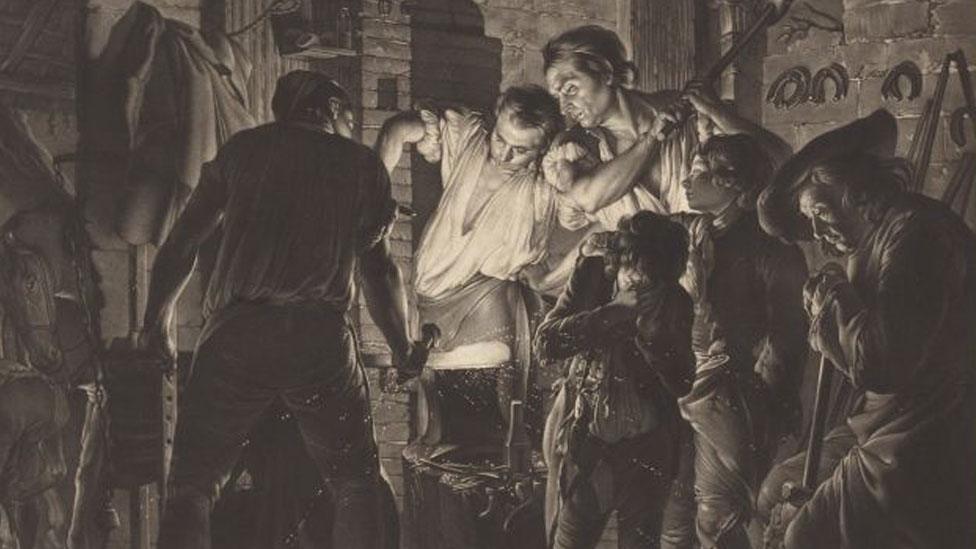

The 17th Century saw a boom in workers such as wheelwrights (above), blacksmiths and shoemakers and a decline in agricultural labourers, the study found

The industrial revolution in Britain may have started 100 years before the mid-18th Century assumption, a study has found.

The Cambridge University research reveals a 17th Century surge in people producing goods and a decline in agricultural workers.

Experts analysed 160 million records - spanning three centuries.

Prof Leigh Shaw-Taylor said: "The story we tell ourselves about the history of Britain needs to be rewritten."

"We have discovered a shift towards employment in the making of goods that suggests Britain was already industrialising over a century before the Industrial Revolution," the professor of economic history said.

"Britain was already a nation of makers by the year 1700."

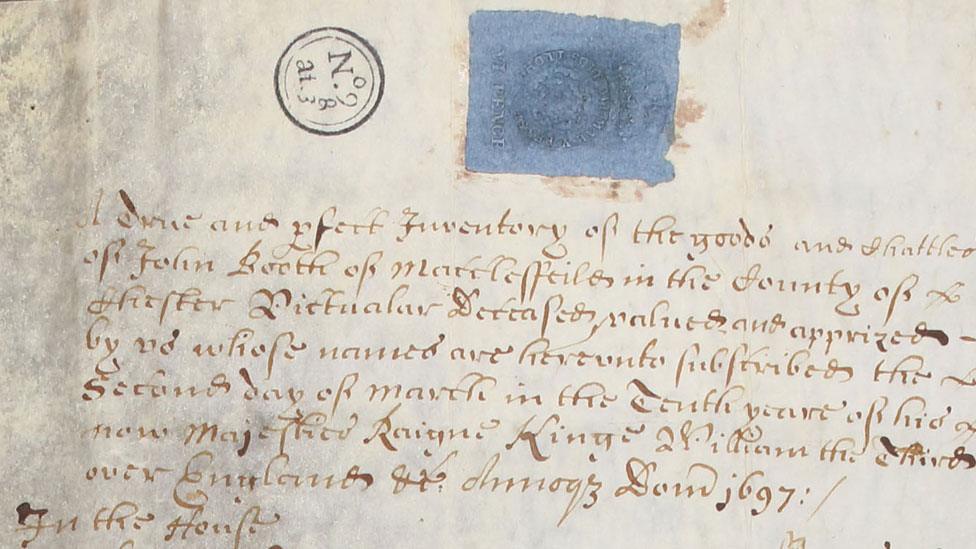

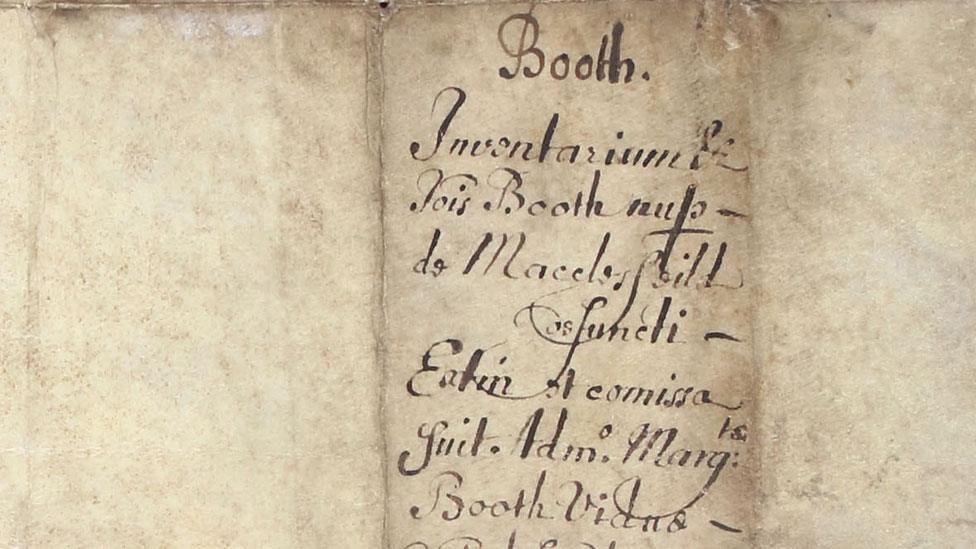

Probate inventories, such as this one for John Booth of Macclesfield in Cheshire in 1697, were among the millions of historic documents analysed

More than 160 million records, including census data, parish registers and probate records from the Elizabethan era to the eve of World War One, were analysed to compile Cambridge University's Economies Past website, external.

This revealed a steep decline in agricultural peasantry in the 17th Century as people manufactured goods.

Workers included blacksmiths, shoemakers and wheelwrights and networks of home-based weavers producing cloth for wholesale.

For example, Norfolk was probably the 17th Century's most industrialised county, with 63% of adult men in industry by 1700.

Documents show John Booth was a victualler and was licensed to supply food and alcohol

Prof Shaw-Taylor estimated the share of the British labour force in an occupation involving manufacturing rather than agriculture was three times that of France by 1700.

While he "can't say for certain" why the change occurred in Britain rather than elsewhere, "the English economy of the time was more liberal, with fewer tariffs and restrictions, unlike on the continent," he said.

By the early 1800s, when William Blake was writing of "dark satanic mills, external", numbers involved in manufacturing had long been flatlining, according to the study.

In fact, by the mid-18th Century - traditionally considered the start of the Industrial Revolution - much of England's South and East had actually lost its long-established industries and even returned to farm labour.

For Norfolk, this meant the number of men working in industry dropped to 39%, while the share of the male workforce in agriculture jumped from less than a third (28%) in the 1700 to more than half (51%).

Evidence of the steep increase in industrial work comes several generations before 18th Century mills and steam engines, when textbooks mark the start of the Industrial Revolution

Meanwhile, parts of Britain "deindustrialised", with workers moving to the coalfields and the 19th Century saw a boom in the service sector, previously considered to have begun in the 1950s.

Workers included sales clerks, domestic staff, professionals such as lawyers and teachers, as well as a huge increase in transport workers on the canals and railways.

As textile production moved out of homes, far fewer women engaged in the labour market from "between 60-80% in 1760, back down to 43% by 1851", the professor said.

"It didn't return to those mid-18th Century levels until the 1980s," he added.

Follow East of England news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp 0800 169 1830

Related topics

- Published3 March 2024

- Published14 January 2024

- Published1 January 2024

- Published20 September 2023