Great Train Robbery: Policeman describes case breakthrough

- Published

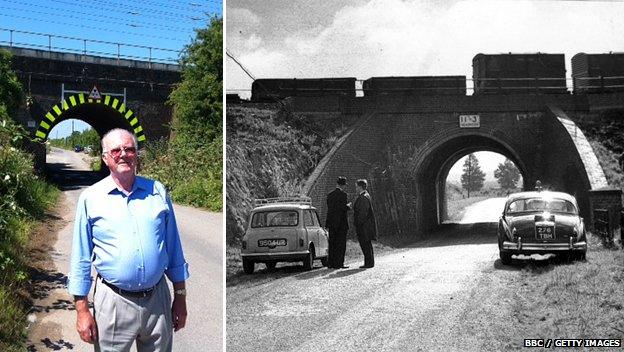

Retired policeman John Woolley has revisited the crime scene at Bridego Bridge in Buckinghamshire

Fifty years after a crime dubbed as one of the greatest of the 20th Century, the police officer who found the abandoned mailbags from the Great Train Robbery, tells BBC News his memories of discovering the gang's Buckinghamshire hideout.

In August 1963, 25-year-old Brill village policeman, John Woolley, responded to one of hundreds of tip offs from the public.

They were keen to help officers find a gang who had robbed the night mail train from Glasgow to Euston, making off with over £2.5m.

John Woolley said he was a "rosy-cheeked 25-year-old" in 1963

As PC Woolley made his way to the empty Leatherslade Farm, near Brill, he was moments away from making a breakthrough in the investigation.

Window ajar

"The middle of nowhere suddenly became the spotlight of the world," said the now retired officer from Upton.

It was at 03:00 BST on 8 August that the train was stopped by a gang of thieves between Linslade and Cheddington.

They broke into the High Value Package coach and made off with 120 mailbags weighing about two and a half tonnes stuffed with £2.6m in used banknotes (about £41m in today's money).

Police called for public vigilance in their search for the offenders and about 400 calls a day were being taken at the incident room in Aylesbury.

It was a tip off from a neighbour which brought Mr Woolley his moment in history.

He and a colleague, Sgt Ron Blackman, went to the supposedly empty farm after a worker became suspicious of activity at the site.

Robbers' provisions

After spotting an upstairs window slightly ajar, Mr Woolley used an old door to climb up to it.

"I climbed in and on the bedroom floor were a number of sleeping bags, a lot of blankets and a little patch of candle stubs," he said.

The pair found the kitchen "absolutely chock a block" with provisions.

"All over the work surfaces, in the cabinets, the larder, it was full of tinned food, packaged food, crockery and cutlery - all you would need for quite a considerably length stay," he said.

Any remaining doubt it was the robbers' was quickly removed when Mr Woolley spotted a trapdoor in the floor, just off the kitchen area.

"I went down the first two or three steps and could see the cellar was absolutely full of bulging sacks," he said.

The gang's hideout was discovered by John Woolley and a colleague on 13 August 1963

"I pulled one of those sacks over to me and saw it was a canvas mail bag - as the top flopped open I could see parcel wrappers, bank note wrappers, consignment notes, all bearing the names of high street banks.

"That was when it finally hit home and we knew without any doubt whatsoever that this was the train robbers' hideout."

The former officer said he felt "excitement and elation" at becoming part of the story of what Fleet Street was already styling the crime of the century.

Forensic experts subsequently found fingerprints at the farm, mostly of convicted criminals, meaning the robbers were unmasked.

Half a century on, Mr Woolley said the crime's continued notoriety was a result of media coverage and misunderstandings.

"The story captured the imagination of the public, but it was because they could not really avoid it," he said.

"There was mass coverage by the press, and the story was never let go.

"It was also erroneously seen as a victimless crime because although the injured driver suffered long term effects, this was minimised by the criminals at their trial."

Indeed Mr Woolley said seeing the gang's criminal records brought home their true characters.

"I knew they were far from being latter day Robin Hoods, they were vicious, greedy criminals who made livings from violent crime," he said.

But as the latest anniversary is reached Mr Woolley believes the story will begin to fade from the spotlight with the 50th likely to be the last milestone to be marked.

"How many of us [who were involved] will [still] be here to remember it?" he said.

"I think it will quietly and fittingly come to rest."

- Published12 July 2013

- Published28 February 2013

- Published18 December 2013