Energy crisis: 'My energy efficient home didn’t keep my family warm'

- Published

Tatiana Hughes found there was not enough insulation in her new-build home after her parents complained of cold bedrooms

With world leaders at the COP27 climate summit, the focus is back on how countries can cut carbon emissions. Since 2008 all homes have needed an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) when they're built, sold or rented, but a firm training EPC assessors says they need redesigning, while some homeowners have found their newly-built houses aren't delivering the high EPC ratings promised.

Heating and powering homes is responsible for about a fifth of the UK's greenhouse gas emissions, external.

Tatiana Hughes' house in Hertfordshire should - according to its EPC - be among the most energy efficient.

It was built in 2016 and scores 91 - a top B rating and just one point off the highest A grade.

But despite the high score, the BBC has seen evidence that two of its bedrooms didn't have sufficient insulation, meaning they became much colder than other rooms.

Mrs Hughes had a special survey carried out in her home to find out why there was a problem

Mrs Hughes, 46, first noticed something was wrong when her family came to visit her three-storey house one October.

"My parents were staying in the bedroom upstairs and they kept complaining it was really cold and asking us to turn the heating on, which I found bizarre because in October it's still warm," she says.

"Then we realised the temperature between the master bedroom and the bedroom upstairs was really quite different."

They paid for a thermographic survey of their house. A surveyor took pictures with a thermal imaging camera to see where heat was being lost.

The report highlighted "notable thermal bridging" in the windows of the second floor bedrooms which, it added, "could suggest no insulation has been installed to the surrounding area".

The loft hatch also showed "cold air ingress" likely related to an "inadequate seal around the hatch".

"It was shocking because you presume when you buy a new house everything was going to be checked and it wasn't," Mrs Hughes says.

"There was a missing piece - somebody didn't check to see if it was done properly."

The builder, Fairview, arranged to have extra insulation installed, which she says has made a difference.

She also says other neighbours reported similar issues and had to have work done.

A spokesperson for Fairview said the firm did not want to respond to the BBC's request for comment.

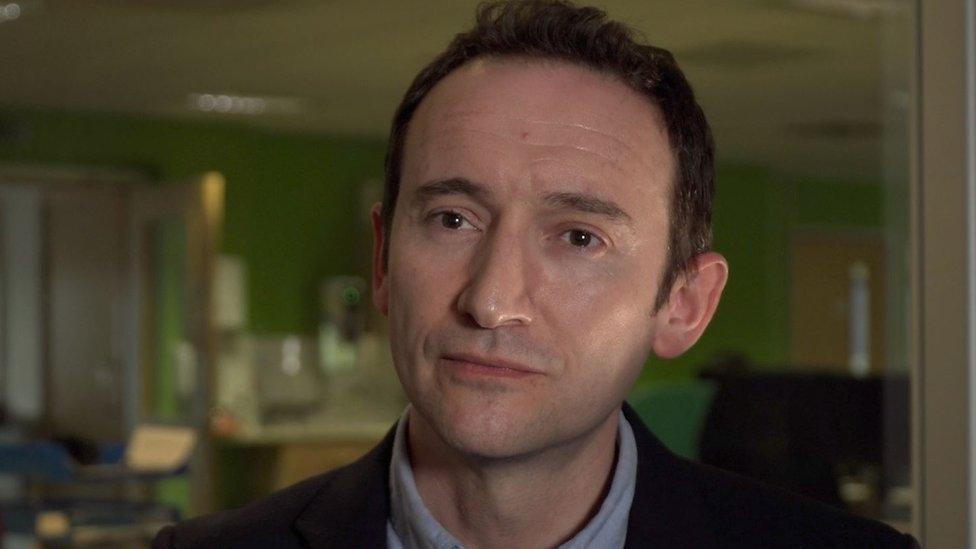

Stuart Fairlie, whose firm trains EPC assessors, says the certificates measure how much homes cost to run, rather than carbon emissions

In 2021, 84% of new-build homes in England and Wales were rated A or B in their EPCs.

Stuart Fairlie, the managing director of Elmhurst, which trains EPC assessors, says Mrs Hughes' experience sounds like a "classic" example of a "performance gap".

Last year their assessors filed more than a million certificates.

He says a "performance gap" is when a developer says they will build a house in a particular way and an EPC is calculated from those plans, but when the house is built, different materials may have been used.

"Somebody has said this house should be a B-rated home, but in reality it was something different," he says.

"You want to make sure that doesn't occur because [when] a homeowner buys a house, if it says B-rated, they should be buying a B-rated house."

Homes were responsible for 22% of the UK's greenhouse gas emissions in 2018, according to government figures

But beyond this issue - which Mr Fairlie says is an "unknown quantity" - he believes there is something more fundamentally wrong with using EPCs to try to cut carbon emissions.

That is because EPC grades - from the top A to the lowest G - were initially designed to combat fuel poverty and are a measure of how costly homes are to run, rather than how much carbon they emit.

He says that means the way EPCs are currently designed won't help the UK meet its climate change target.

"The measuring stick is wrong - the measuring stick is on cost," he says.

"If you want to drive the running costs down of your home, perfectly good.

"If you want to bring up the carbon emissions [in the EPC report], which is already on the EPC but they're just not as in-your-face as we would like, they're further down the document - bring it up, put it up front and centre."

What is an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC)?

EPCs show how energy-efficient a building is and suggests why

They display how costly properties are to heat and light

When a property is sold or rented it needs a valid EPC, which lasts 10 years

Scores range from A-G, with very few properties deemed as top rated As or Bs

EPCs also give recommendations on how to improve a rating

Currently, a property using mains gas will score favourably against one using electricity, as it costs less per kWh (Kilowatt Hour)

Separate ratings for environmental impact are given as the likely tonnes of C02 emitted - but don't measure the actual energy used or C02 emitted

According to the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, homes were responsible for 22% of the UK's greenhouse gas emissions in 2018.

The most recent government figures show between July and September this year, 50% of homes that lodged an EPC were rated D or below.

In its Net Zero Strategy, external, the government said it would consult on whether to phase in higher minimum performance standards so all homes were at least C-rated in their EPCs by 2035, where "cost-effective, practical and affordable".

It is now offering homeowners grants of between £5,000 and £6,000 towards the cost of installing up to 90,000 heat pumps. It says doing so will help save up to 1.1m tonnes (110m kg) of CO2 and is being paid for through a £450m fund.

Homeowner Josh McNally was surprised to discover that his home's EPC rating was not significantly improved by installing an air source heat pump

But when the BBC asked an EPC assessor to evaluate a home after an air source heat pump had been installed, the home's EPC score increased by only one point and it remained at the same B rating.

The home's owner, Josh McNally, who also runs a company installing heat pumps, says: "I would have thought the EPC would have been vastly improved in comparison with what it was before, given we were removing the gas boiler."

Mr Fairlie said it is "clearly wrong" to claim that getting houses to at least a C-rating would help meet the country's net zero target.

"If you say I'm going to get to C, that's a good cost metric, but what we want to see is... an A to G on your carbon emissions."

The government says it is keeping the way EPCs are calculated "under review" and is developing policies to tackle both fuel poverty and decarbonise the county's building stock.

A government spokesman added: "EPCs provide useful guidance for consumers and businesses outlining how energy efficient buildings are in a simple and comparable manner.

"We are already looking at ways the system can be improved through our EPC Action Plan to ensure they are as accurate and effective as possible."

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion please email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published7 November 2022

- Published6 November 2022

- Published28 February 2022

- Published2 March 2020

- Published8 October 2019