What is COP27 and why is it important?

- Published

World leaders are discussing action to tackle climate change at the COP27 climate summit in Egypt.

It follows a year of climate-related disasters and broken temperature records.

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is attending, having previously said he would not.

What is COP27?

United Nations (UN) climate summits are held every year, for governments to agree steps to limit global temperature rises.

They are referred to as COPs, which stands for "Conference of the Parties". The parties are the attending countries that signed up to the original UN climate agreement in 1992.

COP27 is the 27th annual UN meeting on climate. It is taking place in Sharm el-Sheikh until 18 November, external.

Why is COP27 important?

The world is warming because of emissions produced by humans, mostly from burning fossil fuels like oil, gas and coal.

Global temperatures have risen 1.1C and are heading towards 1.5C, according to the UN's climate scientists, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

If temperatures rise 1.7 to 1.8C above 1850s levels, the IPCC estimates that half the word's population could be exposed to life-threatening heat and humidity.

To prevent this, 194 countries signed the Paris Agreement in 2015, pledging to "pursue efforts" to limit global temperature rises to 1.5C.

The Pakistani floods this year are a "wake-up call" to the world on the threats of climate change, experts have said

Who will be at COP27?

More than 200 governments have been invited.

In a speech on Monday Mr Sunak is set to urge world leaders at COP27 to move "further and faster" in transitioning to renewable energy. He will say Russia's invasion of Ukraine "reinforced" the importance of ending dependence on fossil fuels.

Former Prime Minister Boris Johnson is also going, but King Charles will not be there, following government advice. However, he held a pre-conference reception at Buckingham Palace.

Vladimir Putin is not due to go, although Russian delegates are still expected to take part.

Other countries, including China, have not confirmed whether their leaders will attend.

Hosts Egypt called on countries to put their differences aside and "show leadership" on the issue of climate change.

Environmental charities, community groups, think tanks, businesses and faith groups will also take part.

Where is COP27 taking place?

The conference is taking place in the Red Sea resort of Sharm el-Sheikh.

This will be the fifth time a COP has been hosted in Africa.

The region's governments hope it will draw attention to the severe impacts of climate change on the continent. The IPCC says Africa is one of the most vulnerable regions, external in the world.

Currently, 20 million people are estimated, external to be facing food insecurity in east Africa because of drought.

However, choosing Egypt as the venue has attracted controversy.

Some human rights and climate campaigners say the government has stopped them attending because they have criticised its rights record.

What will be discussed at COP27?

Ahead of the meeting, countries were asked to submit ambitious national climate plans. Only 25 have done so to date.

COP27 will focus on three main areas:

Reducing emissions

Helping countries to prepare for and deal with climate change

Securing technical support and funding for developing countries for the above

Some areas not fully resolved or covered at COP26 will be picked up:

Loss and damage finance - money to help countries recover from the effects of climate change, rather than just prepare for it

Establishment of a global carbon market - to price the effects of emissions into products and services globally

Strengthen the commitments to reduce coal use

There will also be themed days, external on issues including gender, agriculture and biodiversity.

Some of the key phrases you will hear:

Paris accord: The 2015 Paris Agreement united all the world's nations - for the first time - in a single agreement on tackling global warming and cutting greenhouse gas emissions

IPCC: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change examines the latest research into climate change

1.5C: Keeping the rise in global average temperature below 1.5C - compared with pre-industrial times - will avoid the worst impacts of climate change, according to scientists

Do we expect any sticking points?

Finance has been long been an issue at climate talks.

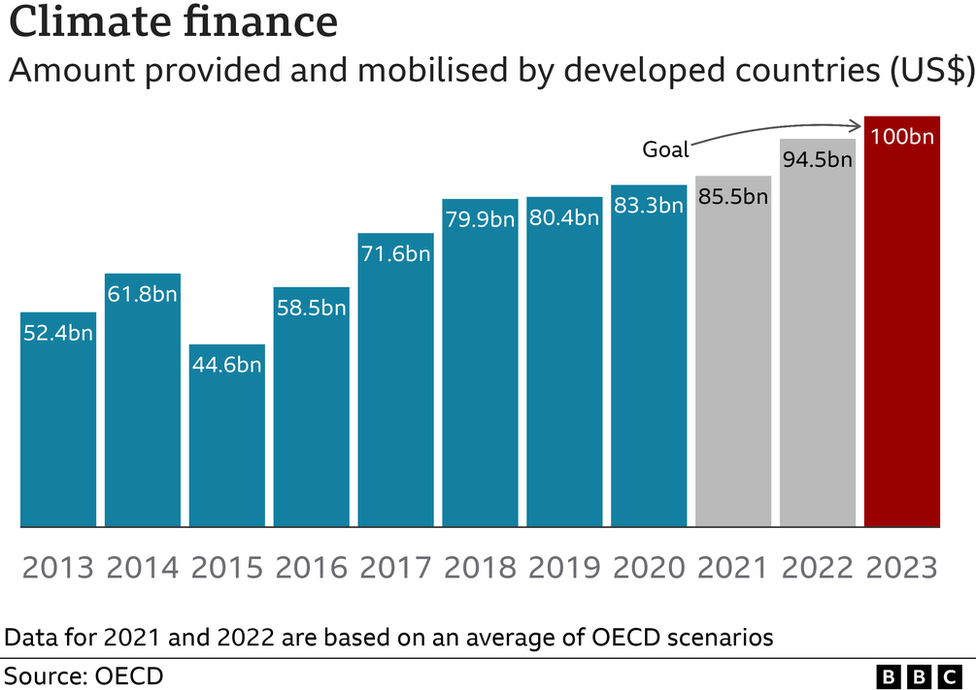

In 2009, developed countries committed to give $100bn (£88bn) a year, by 2020, to developing countries to help them reduce emissions and prepare for climate change.

The target was missed and moved back to 2023.

But developing nations are also calling for payments for "loss and damage" - the impacts faced now.

An option for making such payments was excluded from the Bonn climate talks, after pushback from wealthier nations who feared they would be forced to pay compensation for decades.

But the EU agreed that discussions, external should take place at COP27.

How will we know if it has been successful?

It depends who you ask.

Following intense negotiations, the issue of loss and damage payments is on the official agenda of COP27. Developing countries will also be pushing to have a date set for when they might start to receive payments.

Developed nations will be looking for more commitment from large developing countries - such as China, India, Brazil, Indonesia and South Africa - to move away from coal, the dirtiest of the fossil fuels.

There are also pledges from last year's meeting - on forests, coal, and methane - that more countries may support.

However, some scientists believe world leaders have left it too late and no matter what is agreed at COP27, 1.5C will not be achieved.

Will Greta Thunberg attend COP27?

Climate activist Greta Thunberg is among the list of those who will not attend.

She recently described the global summit as a forum for "greenwashing", saying the COP conferences "encourage gradual progress".

Earlier in October she told the BBC's media editor Amol Rajan in an interview: "I'm not needed there... there will be other people who will attend, from the most affected areas. And I think that their voice there is more important."

Top image from Reuters. Climate stripes visualisation courtesy of Prof Ed Hawkins and University of Reading.