Original Bracknell architect sees his design demolished

- Published

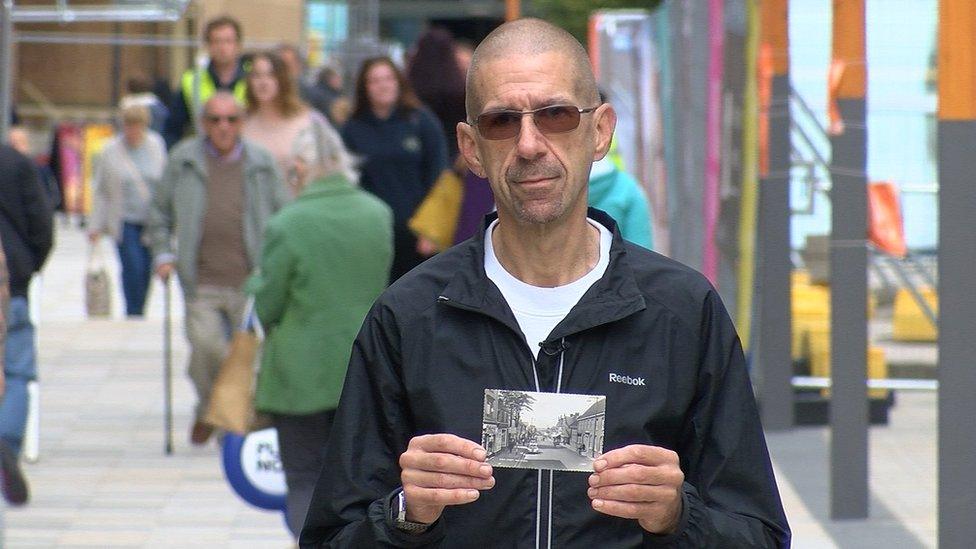

Cyril Minchell designed a Berkshire town, now he's watched it be demolished and rebuilt

Ninety-three-year-old architect Cyril "Minch" Minchell dedicated a large portion of his career to creating the buildings and roads which turned a sleepy rural conurbation into a densely populated, major industrial town. But five decades after his design was finished, he has seen the majority of his work torn down and replaced with a new £240m development.

Critics who described Bracknell as a concrete jungle are ignorant, says the town's original architect, Mr Minchell.

He admits to feeling sentimental about his work and describes agonising over decisions, talking them over with his wife after long days at the office and ultimately the pride he took in seeing his plans come to fruition.

But "unwelcoming" and "underwhelming" were among the less than flattering adjectives used to describe the old town centre by the architecture firm that designed its recent rebuild.

In 2013 its Brutalist architecture led to it being listed as a runner-up in a poll published by the makers of the Crap Towns series of books as they searched for the ugliest places in the country.

Civic chiefs first decided more than 15 years ago that the amenities looked dated and would struggle to attract fresh investment unless dramatic changes were made.

This tower block was among those recently demolished - it stood behind the Red Lion which pre-dated Bracknell's designation as a new town

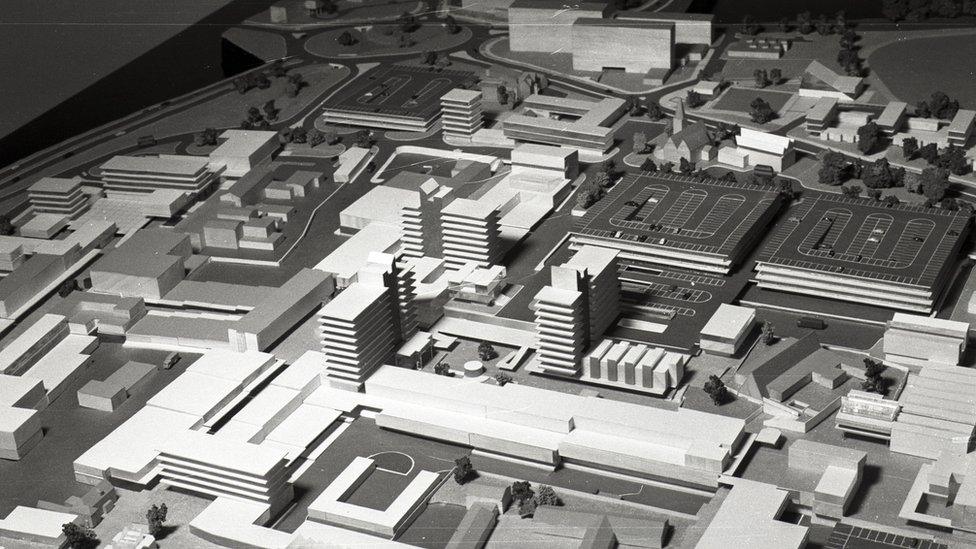

Mr Minchell was working for the Bracknell Development Corporation, which was responsible for building the wider town, when his boss asked him to take the lead on designing the new town centre.

The ambitious young architect, who was married with children, had previously been limited to designing schools and industrial buildings.

"The experience was completely unique," he recalls. "There were so few opportunities like that - so I jumped at it."

It ultimately consumed him for the next 25 years and he is defiant he did the best job he could. So much so he chose to make the Berkshire town his home.

"If it's good enough to build, then it's good enough to live in," he declares.

"I was happy here. I liked the people, I liked my job and I lived here with my wife and watched my children grow up happy."

The site for Bracknell's new town centre was largely demolished by the end of 2013

He says he does not want to be drawn on whether he approves of the decision to knock down so much of his creation, and is quick to dismiss accusations he created a "concrete jungle".

Brickwork is the only material you would have found at eye-level in the town, he explains.

And he says the concrete slabs used were covered with coloured glass to enhance their appearance.

He does not hide his disappointment about some of the choices that have been made in the new development.

The decision that "aggrieved" him more than anything else, he says, was the abandonment of a plan to place a historical mural above a new shop unit.

Mr Minchell says he is saddened a historical mural featured in the town centre could not be incorporated into the new development

"I thought that was wonderful," he adds. "It illustrated the town's history right back to Saxon times. The new authority said 'yes we will incorporate it' and then a few months ago they said 'we're sorry we can't'.

"I hope they put it in storage somewhere safe."

He says he feels similarly sad about the loss of a bandstand he designed which was once used most weekends for entertainment acts.

Mr Minchell also stands by his vision to create a town "at human level" that was safe and comfortable for pedestrians.

"When you are building a town you are building for people," he says.

"I wanted to keep the people away from the cars. Once you parked in the town centre, you didn't have to worry about cars. Children could run around and there was no risk."

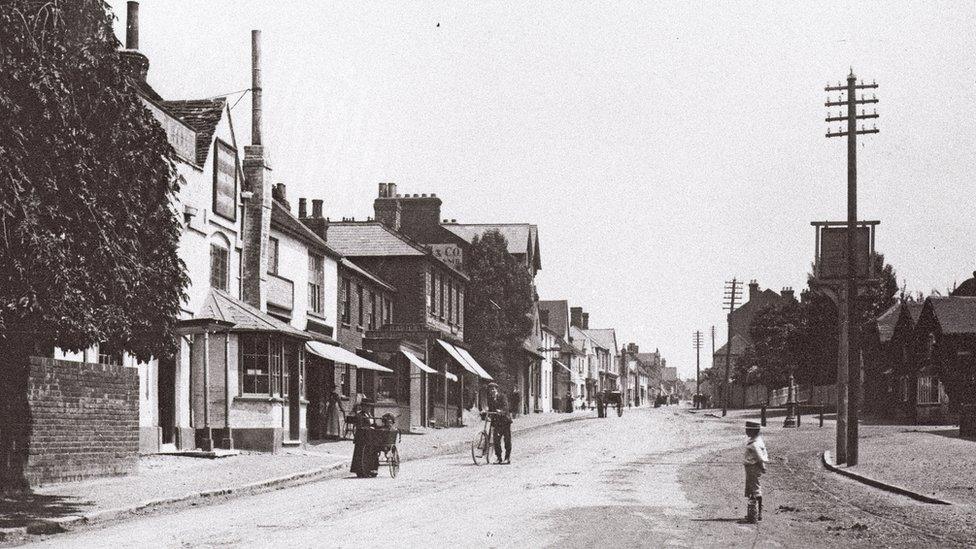

Bracknell had a population of 5,000 before it was designated as a new town in 1949

The task he was presented with in post-war Britain was undoubtedly an enormous one.

There was a shortage of housing in London. Many buildings had been destroyed by bombing. Large numbers of slums were an increasing problem and the birth rate had soared.

Families needed homes and Mr Minchell was the man tasked with turning a small conurbation of 5,000 people into a major overspill town about 30 miles west of the capital, complete with up-to-date infrastructure and facilities.

Mr Minchell has kept photographs of the models he created showing his initial plans

Historian Andrew Radgick says the original residents of Bracknell had been opposed to any development in their quiet town, with it previously being a settlement in Windsor Forest used as royal hunting ground.

It was narrowly chosen ahead of nearby White Waltham for development because of its existing rail links and less fertile agricultural land, he says.

"It was of the time," Mr Radgick says. "Everything had to be brand spanking new.

"Concrete was the new building material. Unfortunately concrete doesn't age very well. That's why everything looks so bad.

"All new towns for people who don't live in them are thought to be concrete jungles.

"Actually if you live in a new town, they are all designed with lots of green spaces. Bracknell as a borough has more trees than any other borough in the country."

Historian Andrew Radgick says Bracknell's design was "of its time" and it proved a "great place to live"

Ambitions to transform the town centre were first unveiled by the council in 2002 after years of rumblings that Bracknell was not keeping up with the modern shopping amenities of nearby Reading and Camberley.

And a host of household brand names quickly signed up to take the vacant shop units once construction began.

Garry Wilding, an architect at BDP which has designed the new town centre, says the work was needed to create "a welcoming, engaging and legible environment for all".

Bracknell's new £240m town centre, called the Lexicon, was built in the hope of attracting fresh investment

"The existing town centre was somewhat hard and unnatural and was unwelcoming and underwhelming," he says.

"It suffered from poor connections, visibility and legibility between its different parts.

"The street patterns were compromised with numerous dead ends, streets leading to underpasses or elevated walkways that didn't feel natural or encourage movement."

Bracknell: Town profile

Cyril Minchell's design for Bracknell has been torn down five decades after it was completed

Population: 110,283

Average weekly wage: £630

Average house price: £323,000

Number of registered businesses: 4,100

Number of people claiming out-of-work benefits: 3,570 (5% of population)

Source: House of Commons Library Statistics

Mr Wilding says the new design - officially named The Lexicon in 2015 - has seen the town centre's appearance "drastically improved".

"We have used a rich materials palette, focusing on natural materials such as timber and brick," he says.

An image showing what part of Bracknell's new town centre will look like

His architectural predecessor, Mr Minchell, says he does "not dislike" what the new designers have produced.

"In fact I think it's rather good," he adds.

But asked whether his own work stood the test of time, he is insistent that it did.

"People don't realise how difficult it is to build something new in an established community," he says.

"Architecture is a very sentimental thing. Under the circumstances we did the best we could."

- Published14 September 2016

- Published4 September 2015

- Published10 October 2013

- Published19 August 2013

- Published23 March 2011