Birmingham New Street station's changing face

- Published

Birmingham's New Street Station has been transformed in a £750m, five-year project that includes the Grand Central shopping centre, which opens on Thursday

For decades, disembarking at New Street railway station could be likened to stepping into a dimly-lit concrete box filled with foetid air.

Its underground platforms, lack of natural light and general aura of grimness even inspired online hate groups, external, while one magazine poll in 2003 voted it the UK's ugliest single building, external.

Now, the Birmingham city centre station has undergone a £600m metamorphosis as part of a wider £750m revamp of the area.

But is the new station a return to the glory days of its 19th Century origins or simply to dazzle commuters?

Live updates from redeveloped station

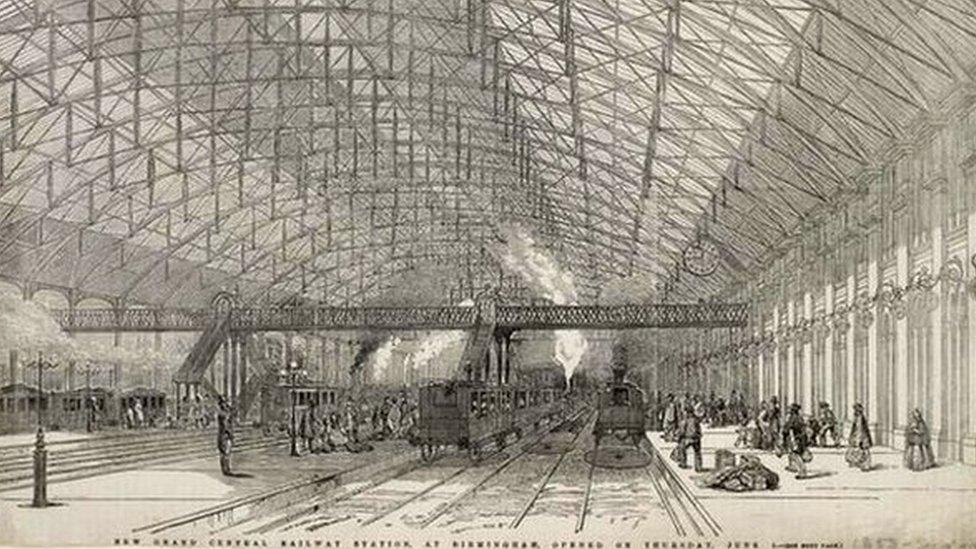

When it opened in 1854, New Street featured the largest iron and glass roof in the world.

It allowed light to stream in and prompted praise.

Author George Borrow, for example, wrote the station "alone is enough to make one proud of being a modern Englishman".

When New Street opened in 1854, it featured the largest single-span iron and glass roof in the world. Platform two, pictured here, was made from both stone and timber

Designed by Edward Alfred Cowper - who had previously worked on the design of the Crystal Palace - the roof was built using 115 tonnes of glass and 1,400 tonnes of iron sheeting

A decade later, Bradshaw's Guide wrote of "broad stone staircases" lined with bronze rails leading passengers down to platforms, and said the roof deserved special attention.

"The semicircular roof is 1,100 feet long, 205 feet wide and 80 feet high, composed of iron and glass and, without the slightest support except that afforded by the pillars on either side," the guide said.

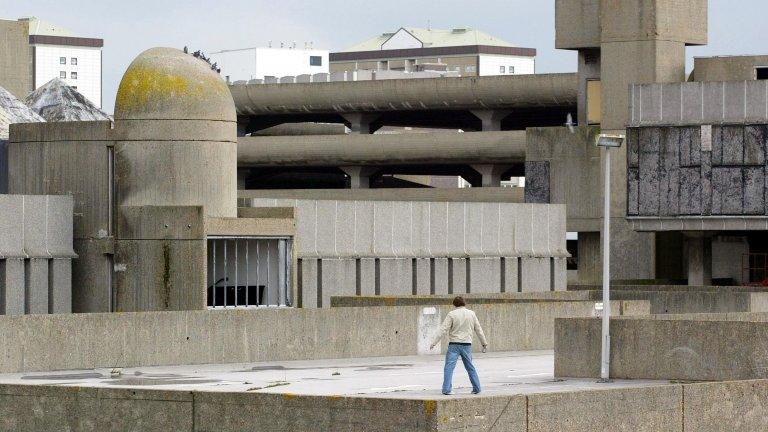

But, the magnificent roof was damaged beyond repair in German bombing raids during World War Two and the station was eventually buried, within its 1967 concrete-reworking.

Now, for the first time since that entombment, natural light is flooding in to the atrium, while the concrete facade has been replaced by gleaming steel panels.

The new concourse, which took two years to build, is some five times larger than its predecessor

Philip Singleton, architect and chief executive of Birmingham's Millennium Point, said the "sheer scale" and the amount of light in the new concourse would surprise regular commuters.

"It feels like a breath of fresh air," he said.

"The old building was so oppressive. Arriving and departing from New Street has been really a depressing experience."

Albert Bore, leader of Birmingham City Council, said the new concourse would create a "vibrant, spacious and bright transport hub" to be "proud" of.

Illustrating how the transformation is not just cosmetic, he also said it would act as a "catalyst" for regeneration and help attract new businesses to the city.

The station is the busiest outside London, dealing with more than 170,000 passengers a day, more than double the capacity of the 1960s building.

The Office of Rail Regulator estimated 34.7 million people made journeys to or from the station in 2013-14, while yet more passed through on their way to other destinations.

By the turn of the 20th Century, New Street had become one of the busiest stations in the country. This view shows it one quieter day in 1885, looking at the westward track

As a result, the new concourse is five times larger than its predecessor and designed to cope with up to 52 million passengers a year.

The revamp includes two new entrances as well as extra escalators and lifts to platforms, which have been decluttered. Work on platform-level though is set to continue for another year.

Construction firm Mace described the project, one of the "biggest refurbishments in Europe", as "demanding, but really successful".

The company said the biggest challenge had been working in a "live" railway station, including installing the new roof while thousands of passengers went about their daily journeys.

More than 6,000 tonnes of concrete have now been removed to allow light to fall on the concourse for the first time since the 1960s redevelopment

The previous concourse, here pictured in the 1980s, was only designed to cope with a fraction of the passengers who now travel through New Street

Network Rail said despite the station being one of the busiest in the country, "very few" trains had been delayed as a result of the project.

Peter Hughes, from campaign group Railfuture, praised the scheme, but wished it could have gone even further.

"The concourse is the most wonderful, dramatic building, but we've always said there's nothing really new at platform level - no extra track and no longer trains," he said.

"The problem is that we're constrained by the narrowness of the site. In a few years new rolling stock should make a real difference, but it's always 'jam tomorrow'."

In the 1960s the station was demolished before entering its "brutalist" phase - buried beneath a car park and propping up the Pallasades shopping centre. The roof of the station was removed in 1964, about three months after this photograph was taken

Before the construction of the Bullring shopping centre, Mr Hughes said there had been an opportunity to allow a little more room for New Street to expand and possibly even add one or two extra lines.

He said another, earlier option had been to turn the derelict Curzon Street station into Birmingham's main hub, until that was adopted as a terminal for the planned HS2 high-speed rail line.

However, Mr Hughes said the central location of New Street was one of its strengths, even if it restricted development of the actual rail infrastructure.

"It's one of the most central stations in any English city. The designers and engineers have done a great job, especially as its continued to be used by passengers," he said.

The project has not been without its problems.

Original designers AZPML and its lead architect Alejandro Zaero-Polo, pulled out of part of the project last year in a row involving materials.

Cramped conditions during the revamp also played a role in the station being named the UK's worst in a survey last year, by rail watchdog Passenger Focus.

- Published20 September 2015

- Published24 August 2015

- Published2 August 2014

- Published31 July 2014

- Published28 April 2013