Six ways the town of Rugby helped change the world

- Published

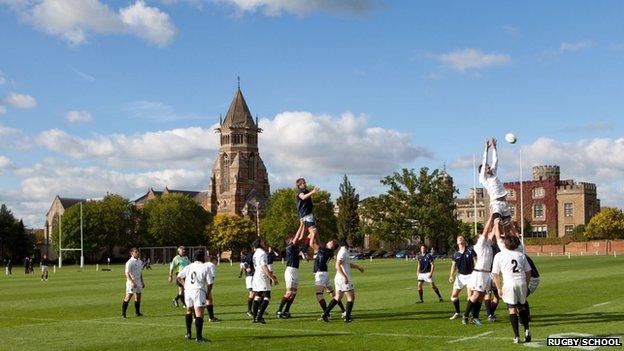

Rugby School helped invent different versions of the sport that are played throughout the world

The town of Rugby in Warwickshire is arguably best known as the birthplace of the sport that bears its name. But it also lays claim to having helped inspire the modern Olympics and the "Harry Potter of its day". So what else has it done?

Most people know the story.

It was 1823, on a school field at Rugby School that senior boy William Webb Ellis, caught a football in his arms and began to run with it.

It was this moment, according to folklore, that led to the invention of not one, but several, international sports.

As the annual Six Nations tournament - which styles itself "rugby's greatest championship" - prepares to grab fans of the union code in its thrall once more, what more has this Warwickshire given to the world?

The invention of rugby

Somewhat confusingly, what the world knows as "rugby" is still known as "football" in the school that bears its name.

And football in the 1820s was a world away from the sport we know now.

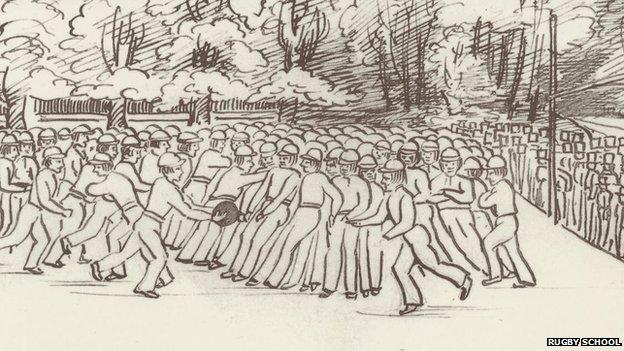

Ball games at Rugby School could involve hundreds of boys and matches could last for days

"You could have up to 300 boys on the pitch at any one time," said Rusty MacLean, the school's archivist.

"Teams could be of vastly different sizes and matches could last for a week."

It was the boys themselves - the "Rugbeians" who took charge of codifying school sports.

"Ellis was a senior boy in 1823, a praepostor, or prefect," said Mr MacLean. "One of the unwritten rules of football said you were allowed to catch the ball but not run with it. Ellis is credited with being the first person to run with the ball."

In 1845, three Rugby boys produced what are believed to be the first written rules of "the Rugby style of game".

A later pupil, Tom Wills, is credited with taking the game to Australia, where it morphed into Australian Rules Football, while a 1911 history of American Football cites the school as the "cradle" of the United States' game.

Mr MacLean said much of the terminology of the sport, such as "offside" and "touch" also originated on "The Close" - the Rugby playing field.

In 1839, Queen Adelaide visited the school and the boys wore what is believed to have been the first games kit, complete with crimson caps. "Those caps are why we refer to players receiving an international cap today," said Mr MacLean.

So how true is the Webb Ellis story likely to be?

Tony Collins, a professor of history at De Montford University's International Centre for Sports History and Culture, said there is no evidence to support the legend but does credit the school with codifying and popularising the sport.

"You can certainly trace the origins of both Rugby League and Union to the game that was played at Rugby School."

The birth of the modern Olympics

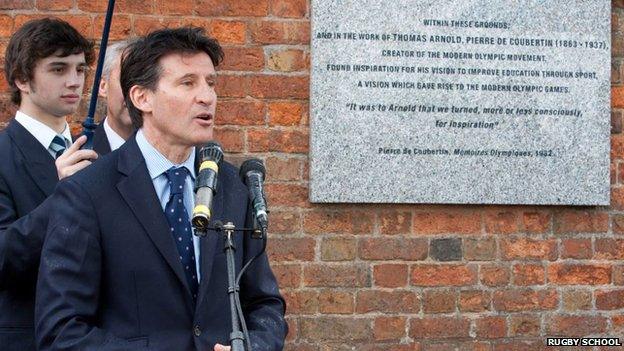

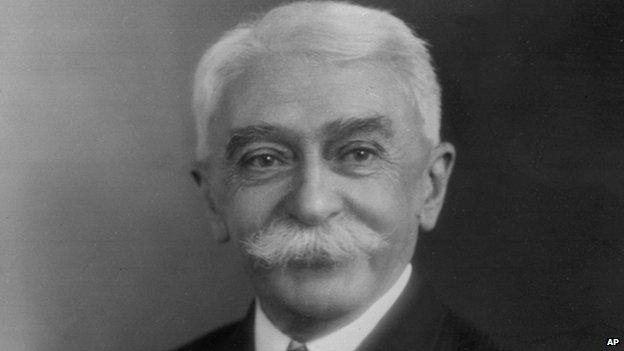

The founder of the International Olympic Committee, Pierre de Coubertin, made no secret of the role Rugby School and its famous headmaster, Dr Thomas Arnold, played in inspiring him to found the modern Olympic Games.

"De Coubertin was an educational reformer in France," said Mr MacLean. "He visited the school on several occasions and is even said to have spent a night in the chapel, where he is said to have had his light bulb moment for the modern Olympics."

De Coubertin wrote: "It was to Arnold we turned... for inspiration."

Lord Coe unveils a plaque commemorating Rugby's contribution to the modern Olympics

Pierre de Coubertin acknowledged that Rugby School inspired him to create the modern Olympics

Mr MacLean is clear there were other influences on de Coubertin, not least the games in Much Wenlock.

"I don't think you can say the Games would not have happened were it not for Rugby School but the original catalyst was Dr Thomas Arnold," he said.

"In many ways, he was trying to take the values of Rugby School to the rest of the world," added Professor Collins.

The English school novel

The book that seared the myth of Rugby in the mind of nearly every scuff-kneed schoolboy in the second half of the 19th Century- including de Coubertin - was the original school story bestseller Tom Brown's Schooldays.

While English fiction had seen previous stories set in schools, by former Rugbeian Thomas Hughes was the first to gain mass popularity with the genre.

"Hughes was very much influenced by Thomas Arnold and he didn't write the work as entertainment - it was originally a didactic work designed to advance Arnold's philosophy," said Mr MacLean. "It's set within a school and it's about good triumphing over evil."

It is a familiar tale that resonates down the generations and, according to some, Harry Potter, is the "modern Tom Brown".

"You could clearly see Tom Brown as the forerunner of Harry Potter," said Mr MacLean. "Tom Brown is Harry Potter, Dr Arnold is Dumbledore, Malfoy is Flashman and Quidditch is a game of football. And, like Harry Potter, the reader wants Tom to triumph against the odds."

"The Harry Potter books, like Tom Brown, regard school as a space where that character's battles take place," added Pablo Mukherjee from the University of Warwick's English and comparative studies department.

"In many ways, Harry Potter revises the Rugby School ethos."

The English gentleman

It is rare that one man is credited with forging a template for standards of British public life, but some historians see Dr Arnold, Rugby's headmaster from 1828-1842, as playing that role.

Thomas Arnold, Rugby School's most famous headmaster, was enormously influential on the lives of his pupils

"He defined to others this idea of responsibility and service. He created a generation of people who became great leaders," Mr MacLean said.

When Dr Arnold took up his post, Rugby School was, according to journalist and historian Simon Heffer, a "run-down and unfashionable school".

"Within 15 years, he had inculcated a generation of intelligent young men," said Mr Heffer, who has devoted the preface of his study of the Victorians - High Minds - to Dr Arnold.

"I see him as being one of the most influential figures - not of the Victorian era, because he died five years after the queen came to the throne - but on it.

"A number of men who worked at the school or were pupils there did things in society that propagated the Arnoldian message.

"It meant that in a society where many people were poor and struggling, there was a duty on behalf of those who were educated to go out and improve the lot of others.

"He didn't invent the stereotype of the English gentleman but he did contribute to it."

The jet engine

Another world-changing idea that took off in Rugby was the jet engine.

A prototype for the engine was built by Sir Frank Whittle, a Coventry-born RAF engineer air officer, at the British Thomson-Houston (BTH) works in the town in 1937.

Sir Frank Whittle built the prototype for the jet engine at Rugby

"Rugby was a major player in the development of the jet engine," said Barry James, chairman of the Midland Air Museum board.

"Sir Frank was a man who used all the engineering skills of the area to develop his invention. Rugby was his area and BTH had the capabilities he needed."

Unfortunately, Mr James says, the people of Rugby were not able to appreciate the revolutionary nature of Sir Frank's invention - in fact, they found the loud noises caused by the testing disturbing, a fact not helped by their top secret nature.

"People started to talk and ask questions about what was going on, so in the end the development moved away from the town," said Mr James.

Air historians say the jet has helped change world history

But there is no doubting the jet engine's impact on the world.

"The jet has had a significant impact on civil and military aviation," said Mr Van Schaardenburgh.

"Although transatlantic flights were possible with the old piston engine, the jet allowed you to fly higher, where there was less air resistance, and go further."

Rugby Radio

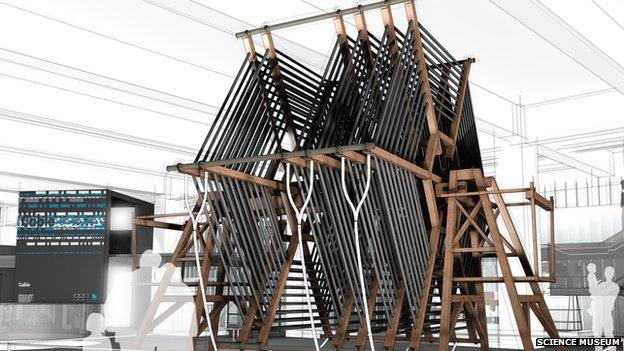

The enormous Rugby Radio Station tuning coil was erected by the government in 1923 to enable communication to all of Britain's colonies.

When Rugby Radio came on air on 1 January 1926 it was served by the world's most powerful telegraph transmitter.

The technology was used for communicating everything from Christmas greetings to the navy to telegrams abroad.

The Rugby tuning coil was used to send messages throughout the world, following its erection in 1923

"The Rugby tuning coils are a wonderful reminder of worldwide radio communications in their early pioneering days," said John Liffen, curator of communications at the Science Museum.