The farmers who started out with student debts and big dreams

- Published

When Lewis Steer was 16, his parents gave him three sheep as a reward for doing well in his GCSEs.

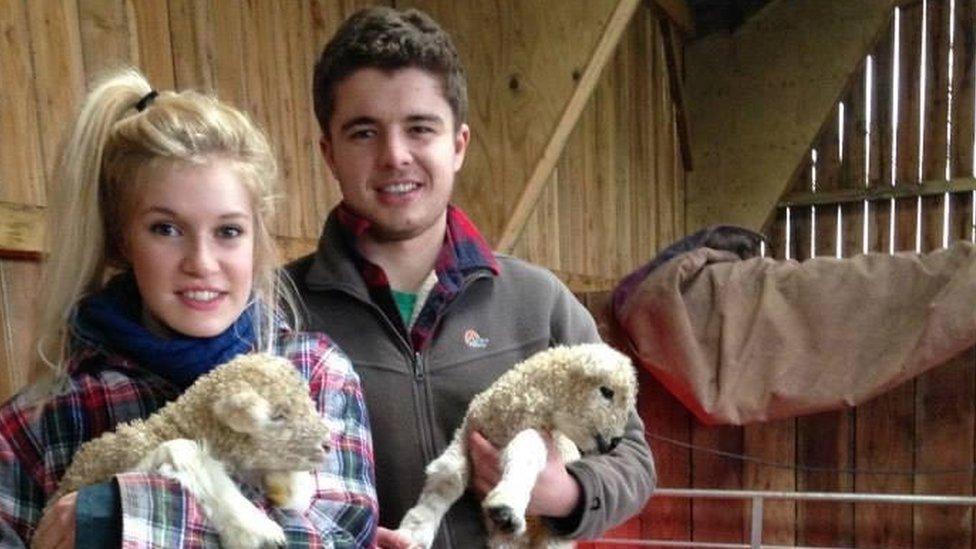

It was an unusual present but Lewis and his girlfriend Flora Searson had an unusual goal - despite coming from non-farming families, they dreamed of running their own farming business.

Now in their mid-20s, that's something they're doing, rearing three flocks of rare-breed sheep on rented land in Dartmoor, Devon.

They explain what it's been like breaking into an industry that's often associated with a suspicion of outsiders.

'I thought I had to be somebody else'

Neither Lewis nor Flora had a farming background; Lewis's parents were greengrocers and Flora's were teachers.

"I've always wanted to be a farmer all my life… you get toddlers who want to be a farmer and go through the farmer stage - I never left the farmer stage," Lewis says. "I never actually thought I could be a farmer - I thought I had to be somebody else and maybe one day retire to it, or do it on the side.

"To encompass the whole feeling of not being from a farming family, it is hard and it brings a lot of challenges, and life in a lot of ways would be a lot easier if we did have 500 acres that mum and dad had had for generations."

'We had nothing to lose'

The couple, who met aged 16, built up a small flock of 40 sheep while studying at university, keeping their animals in a rented field.

"It was a hobby, really, that earned a few quid on the side to help with uni," Lewis says.

"We could only rent one field off this farmer because she said we didn't know how to look after the rest of the farm. Ironically, now we rent the whole thing - it's one of the smallest farms we rent. It's quite satisfying."

Flora studied creative media practice at Bath Spa University, while Lewis studied rural estate and land management at the Royal Agricultural University. After getting their degrees, they returned to Chagford, Dartmoor, where they both grew up.

"If there was going to be any point in our lives to go and give this a punt it was then, because we had nothing to lose, really," Lewis says. "Just student debt and 40 sheep. So if you're going to try it and it fails, our logic then was so what, it doesn't matter."

"We weren't paying ourselves anything for a long time," Flora says, "so the fact that we are now most of the time is a big step for us."

'Farmers don't like change'

"Trying to find the land was hard," explains Lewis, who says they have 13 different landlords.

"We struggled still up to six months ago as we were short of land and, to be honest, after lambing we'll probably be short of land again," he says.

"It's very difficult to persuade someone to sign a tenancy with a young couple - a young couple not from farming who are breeding rare breeds and deemed economically unviable, and a young couple doing all that but not just selling lambs like a sensible farmer, but producing handbags and sheepskins."

Flora says it's not always easy for landowners to break with convention. "It's the type of thing, once you've had one farmer there, you just have them until they decide they don't want it... and their son or daughter will carry on," she explains.

In order to survive as first-generation farmers, Flora and Lewis have diversified. "We haven't inherited so we've had to diversify because otherwise we just couldn't pay our rent," Flora says.

As well as selling lambs, the couple use the heavy wool from their flocks of native Dartmoor sheep to make products such as throws, handbags and rugs, which they sell at markets and shows.

Sheepskin throws are among the products sold by the couple

"The inherited generational farmer is struggling to make ends meet doing it the traditional way, so how on earth would we enter the industry doing it that way?" says Lewis. "If they're struggling with what they've got to make ends meet doing it that way, there's not a hope in hell we could ever enter it brand new with all the investment and everything and the other issues we face doing it that same way."

In part because of their unconventional approach, the couple say they found it hard to win the acceptance of the close-knit farming community.

"Some people welcomed us in with open arms and helped us out, others were a bit suspicious and wary of us because we were doing something really different," Flora says.

"Once you're in it, it's a lovely community to be in... but getting in it was tough," Lewis says. "I think it's because they don't understand, they don't like change and they don't see us as proper farmers."

What help is there?

In the 1940s, about 10% of the population was involved in farming - that figure is now below 2%

"Bringing new people in with ideas is invaluable," says John Thorley, chairman of the Henry Plumb Foundation, which helps first-time farmers to build their business by providing support and an experienced mentor to guide them.

"We try to make sure that the opportunity of bringing someone new into the industry isn't lost," Mr Thorley says. The foundation looks at business prospects and "if there's a chance we will put heart and soul into helping".

Finding affordable land is a big factor for first-generation farmers, says Mr Thorley, a former chief executive of the National Sheep Association.

In the 1940s, when Mr Thorley was born, about 10% of the nation's workforce was involved in farming, a figure that has fallen to about 1%. According to Defra, the average age of a farmer is 60 and only 3% of farmers are under 35.

'We don't know any other way'

Being first-generation farmers means they have a fresh perspective, Flora and Lewis say.

"One thing we do have is that the decisions we make are our decisions and if they go wrong, they go wrong for us and if they go right, they go right for us," Lewis says.

"It allows you to look at everything critically and everything with a fresh pair of eyes and be very objective and businesslike. We don't think, 'we'll do that because that's how we've always done it'. We've never done it, so we'll do it the best way there is to do it for us, because we don't know any other way."

The couple think one reason first-generation farmers are a rare breed is because young people might see farming as "completely inaccessible". "I don't think you'd ever just think 'well that's what I'm going to do' if you didn't have any link to it," Flora says.

"Some people might not think of it as a diverse, exciting job because they are used to the agricultural stereotype of a farmer as a person who is in their 60s in scruffy old tweed, squelching around, and it's not that," Lewis adds.

"It's exciting, it's dynamic, it's brilliant. There's a growing number of youngsters who want to do it. There is a bubble of people with really cool, fresh ideas and if they can just be given the opportunity they could be brilliant for the industry."

- Published23 August 2019