The art of hunting down stolen treasures

- Published

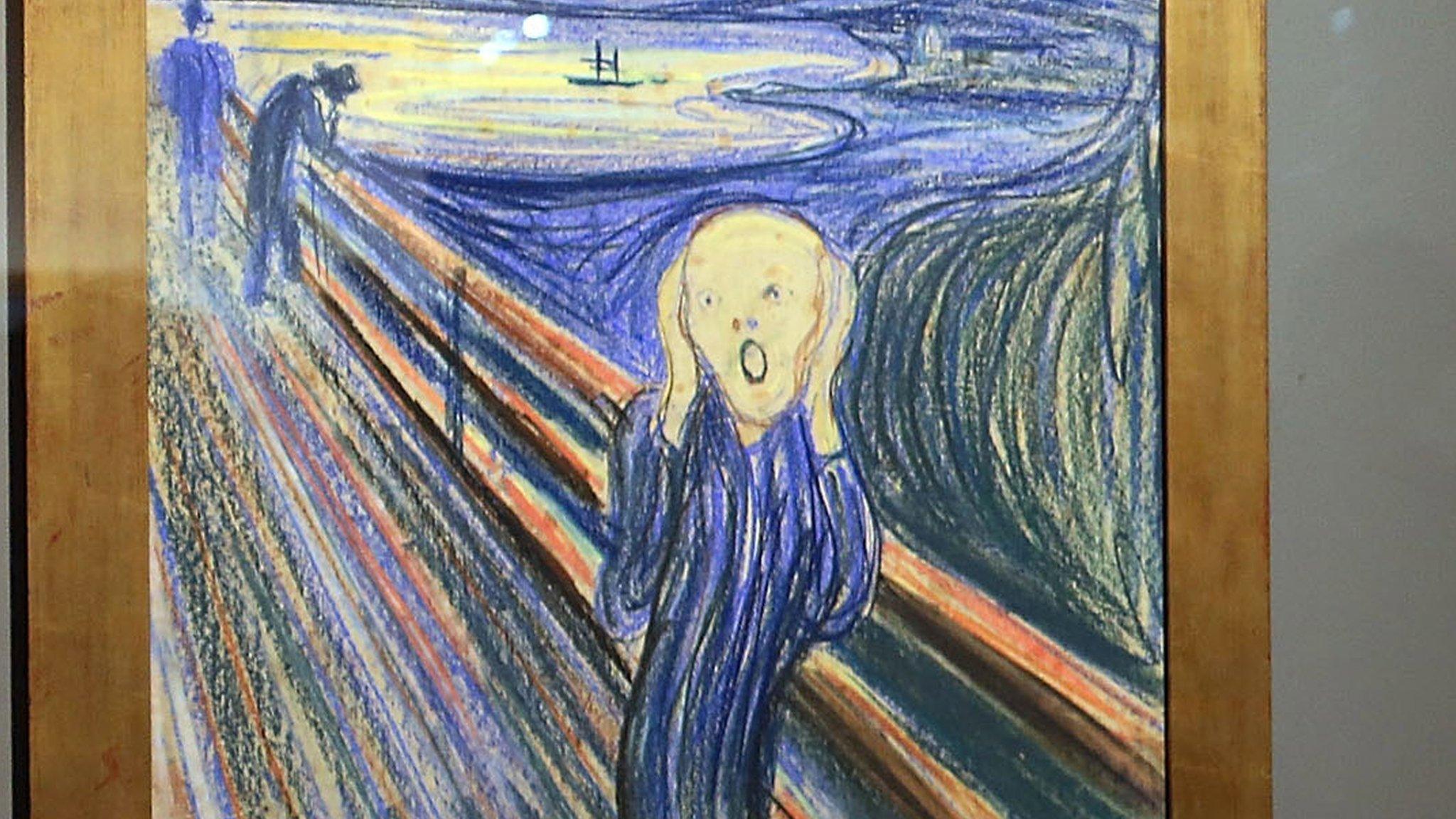

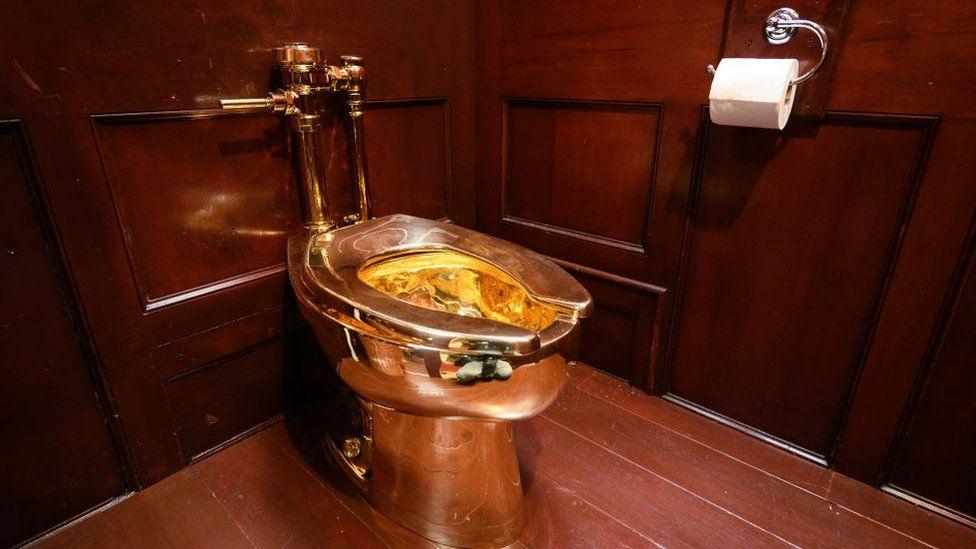

The fully functioning solid gold toilet - worth nearly £5m - was installed at Blenheim Palace as part of an art exhibition

Only a day after it was plumbed into one of Blenheim Palace's grand rooms, a solid gold toilet created by artist Maurizio Cattelan was ripped out and stolen.

More than two months later, police are seemingly no closer to bringing charges over the raid, described as being like something from a "heist movie".

Renowned art detective Charley Hill explains the complexities of solving such crimes.

Charley Hill led an art and antiques recovery unit as a Scotland Yard detective

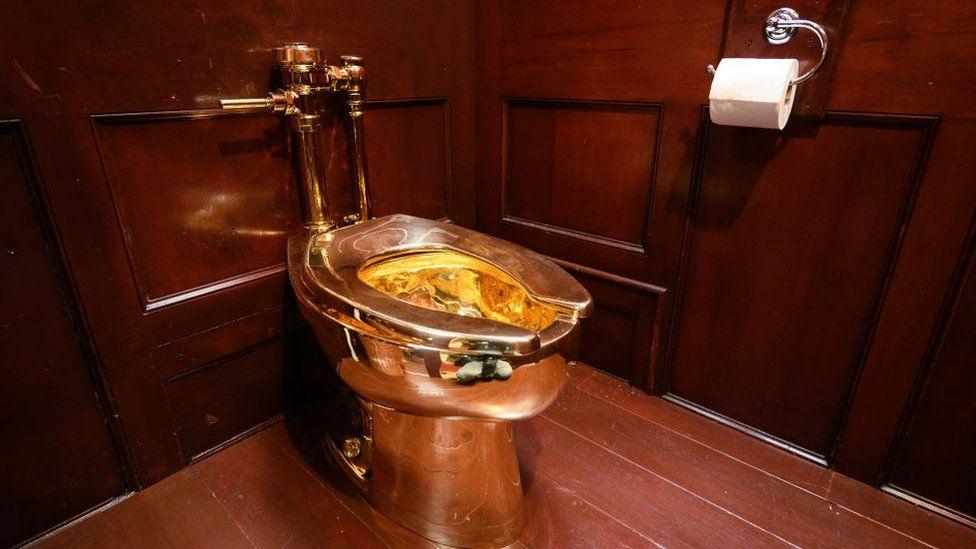

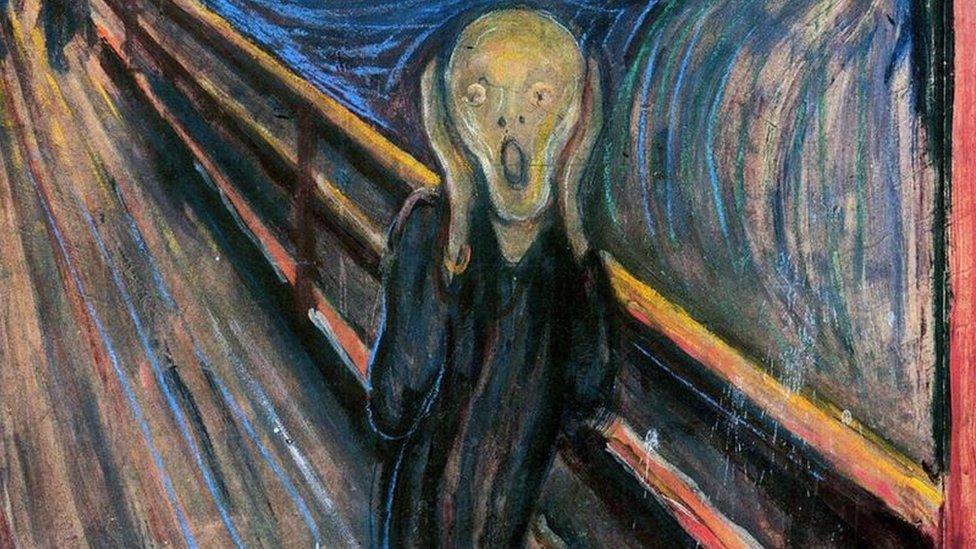

Mr Hill knows what he's talking about, having helped solve one of the most high-profile art crimes of the 20th Century - the 1994 theft from an Oslo museum of an 1893 version of Edvard Munch's The Scream.

The Norwegian authorities called in Mr Hill's then employers, the Metropolitan Police, for help in finding the painting, which was taken with embarrassing ease., external Posing as a "slightly dodgy, mid Atlantic-accented art dealer", the undercover detective sergeant managed to make contact with the criminals responsible.

Beforehand, Mr Hill had done his homework. "In that particular version, the original version, he [Munch] blew a candle out on it. I made a particular point of memorising exactly how those candle wax drops looked."

Having persuaded the thieves he was willing to buy the painting, they took him to a summerhouse where the artwork was stored in a basement. "I knew the picture was right straight away because I checked the wax."

"A masterpiece will tell you itself that it's a masterpiece - it just jumps out at you"

Before his involvement in the recovery of The Scream in May 1994, external, Mr Hill's most successful case was leading the 1993 investigation that found paintings by Vermeer and Goya, which had been stolen seven years earlier from Russborough House in County Wicklow.

His "eye" for such cases led to him heading up his own art theft squad at the Met. "I look at things and I can see whether they are real, unreal, or old or new. I can do things like that," he says.

He left the police in 1997, but his global reputation means he is never short of clients. Mr Hill is usually contacted by victims and he then decides whether he wants to take on the case.

On 12 February 1994, it took thieves less than a minute to climb a ladder, smash through a window of the Nasjonalmuseet in Oslo and cut The Scream from a wall

His days of creating fake identities are over and he doesn't conduct undercover operations any more. Now Mr Hill's central tactic is a simple one - "talking to people".

"It's the only way, effectively; you'll find out what's going on, who's done what and in my case where things are." He says he doesn't "deal in ransoms" or "engage in 'art-napping'" but relies on his "very useful" reputation to recover stolen treasures.

"When I talk to people, like the convicted criminal I spoke to a couple of nights ago... she knows about me and is interested in meeting me and talking to me," the 72-year-old says.

Speaking to those "who have access" but are "generally quite far down the line from the actual thieves" is one important tactic. Mr Hill says those who supply information to complete the jigsaw can include informants, experts and in some cases, convicted criminals.

The former police officer says he will continue trying to recover lost art for as long as he can

Mr Hill loves art, a passion that started as a child in the US, where, because of his American father, he spent his school years. While he accepts there's a "romantic view of art theft", he actually finds it a "depressing" crime.

"I believe these are works of creation by human beings, that these inanimate objects have lives of their own... they are worth preserving, protecting and keeping for us and future generations."

You might also be interested in:

Mr Hill is still trying to retrieve artworks taken in a 1990 raid on the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston

Since going freelance, the Vietnam veteran says his perspective has changed somewhat.

"I have got no interest at all in arresting people, however with this kind of crime you want to get these things back, and sticking somebody up in front of a court is pointless - it doesn't actually recover these things.

"I do a lot of research but my main tool in my kitbag is my capacity to talk to people and go back later and talk to them again."

In the course of getting the information he needs, Mr Hill says he sometimes turns a blind eye when "people tell me about things I can do nothing about".

He admits some see his work as meddling - or even something that's "outrageous and shouldn't be done".

"I never break the law, but I do [annoy] the police," he adds. "I wouldn't say I'm a rogue because I am not dishonest. I'm not doing it for some ideological or commercial gain."

The toilet was stolen on 14 September from Blenheim Palace, near Woodstock - the stately home is the principal residence of the Duke of Marlborough

So what does he think has happened to the gold toilet?

A month before it was stolen, Edward Spencer-Churchill - half-brother of the Duke of Marlborough - said the artwork was "not going to be the easiest thing to nick". The thieves thought differently.

Mr Hill, who lives in Richmond in south-west London, doesn't believe the toilet was taken to order for a rich client - "the stuff in movies is by and large rubbish" - and is doubtful whether the piece even exists any more.

Because as a work of art it will have been "meaningless" to the thieves, his view is a mob of low-level criminals will have destroyed it. "All they know is that it's made of gold and they have a few bob coming if they cut it up, melt it down and flog the gold," he says.

Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan has said he hopes the toilet theft was a "kind of Robin Hood-inspired action"

It's safe to say the owner of the toilet is unlikely to call in Mr Hill to crack this crime, but he isn't short of work.

He says he's close to solving the theft of 13 artworks from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston in 1990 - a case he's been working on for more than 25 years.

The museum is offering a reward of $10m (£7.75m) for information leading directly to the recovery of all 13 works in good condition, but for Mr Hill - who says these days he only asks for his clients to cover his expenses - it isn't about the money.

"I love art and I know the important thing is to get the stuff back," he says. "Someone has got to do it; who else is going to get these things back if I don't try?"

- Published16 October 2019

- Published14 September 2019

- Published12 February 2014