Is this hairy crab the newest species found in the UK?

- Published

The crab has a square-shaped shell and is covered in tiny bristles

A colony of exploding ants, a shrimp that's been named after prog rockers Pink Floyd, four types of miniature night frog and a coconut-cracking giant rat - these are just some of the new species discovered in the past year.

While all of these exotic creatures were found many thousands of miles away from Britain, such discoveries aren't the preserve of scientists in the remotest part of some far-flung wilderness. In fact, it's estimated there are thousands of species yet to be identified in the UK alone - and many millions globally.

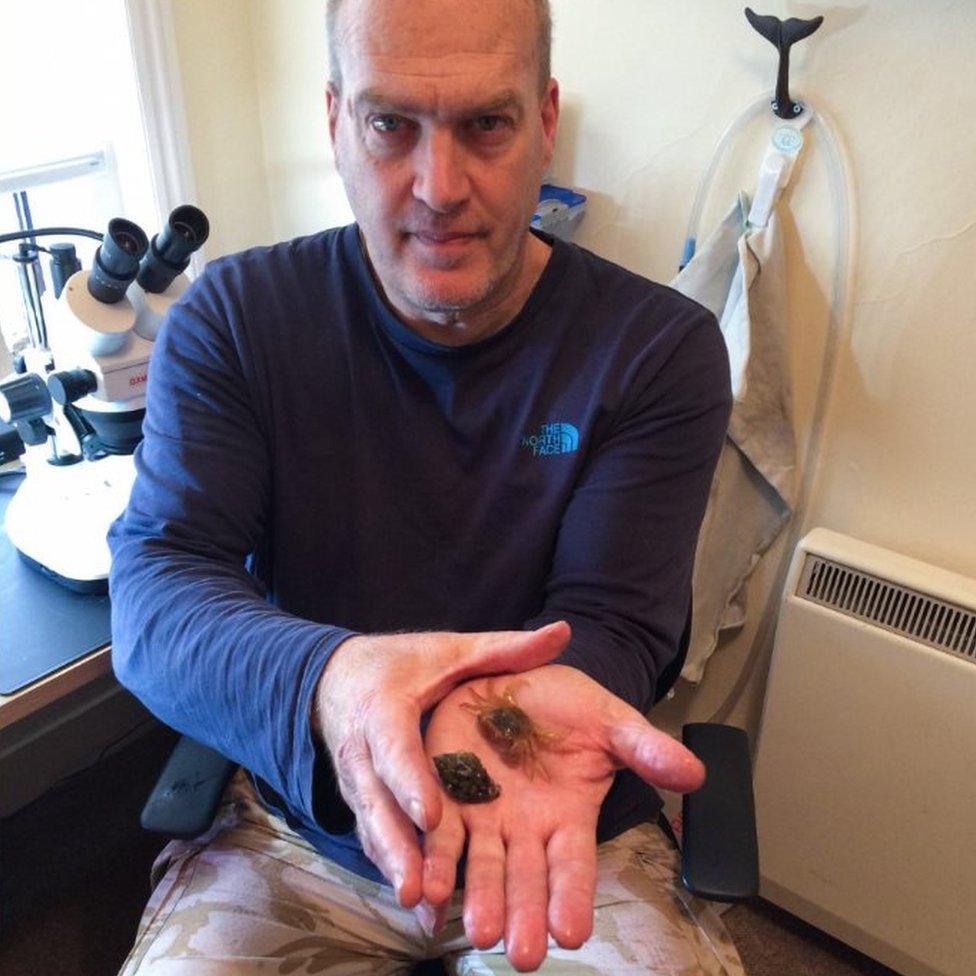

The hairy crab that's potentially the latest new-to-science domestic discovery was collected by naturalist and photographer Steve Trewhella on Chesil Beach, near Weymouth, in Dorset.

The 2cm-wide creature was found living inside a polystyrene buoy that washed ashore following a storm and is suspected to have travelled across the Atlantic from the Caribbean.

Mr Trewhella, who has sent the crab to the Natural History Museum for identification, hopes the tiny crustacean could prove to be his greatest success story.

Steve Trewhella keeps many of the live creatures he finds in tanks at home in order to study them

"I was ungraded in every single subject I took at school - I failed miserably," says Mr Trewhella, who runs a cleaning business to help fund his passion for nature.

"I was that geeky kid by the pond or with my head in a rock pool."

He's been waiting patiently to discover if his fascination with nature might cause his name to be recorded in posterity.

"They're now looking for samples of DNA from other Caribbean hairy crab species to try and eliminate or compare, but it's a long process," Mr Trewhella says.

"It'd be nice to have an elephant named after you but elephants are easy to find and hairy crabs aren't, so the more obscure the better."

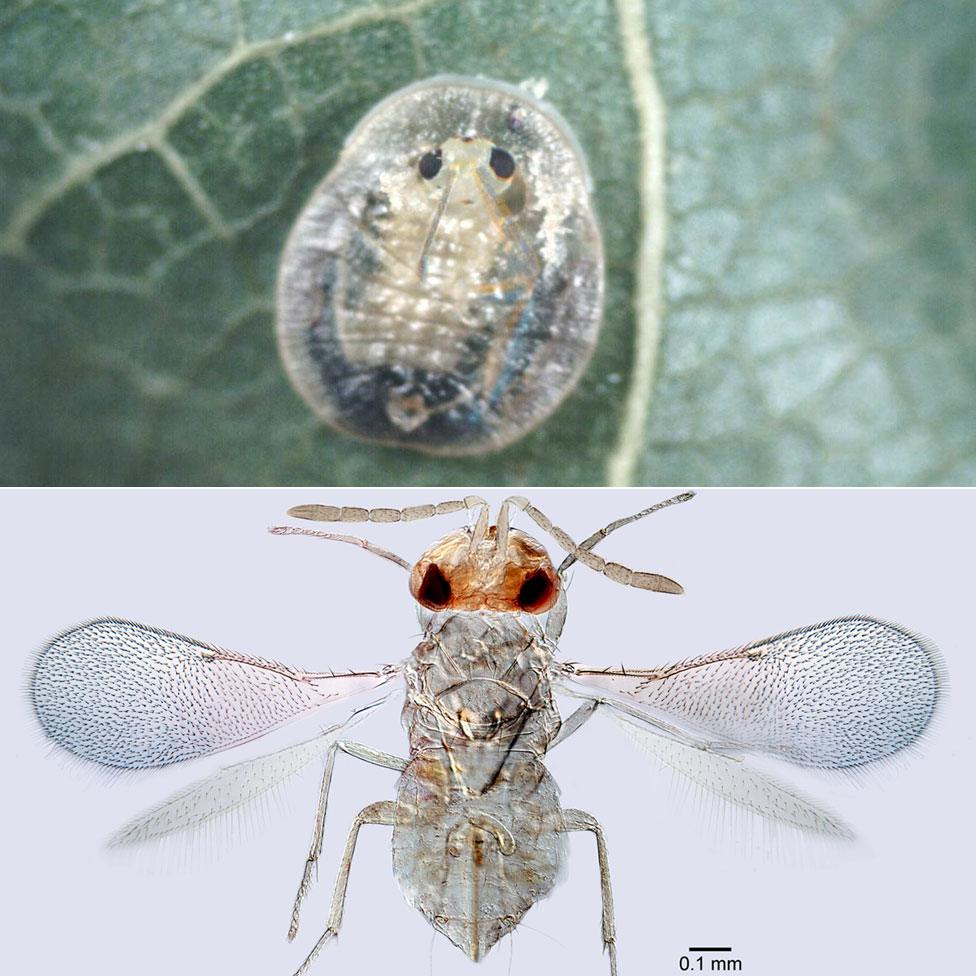

In 2016, Mr Trewhella found a springtail that hadn't been recorded in the UK for 34 years

Scientists estimate there are about 8.7 million species on Earth, yet only a surprisingly small number - 1.2 million - have been formally identified.

In the UK, more than 70,000 species of animals, plants, fungi and single-celled organisms have been recorded.

Dr Peter Shaw, the UK's official recorder for springtail bugs, says some domestic habitats remain "remarkably unexplored".

"There are many microscopic creatures that haven't yet been recorded, not because they're not there but simply because people aren't looking for them," he says.

"Humans are more interested in the bigger, more conventionally attractive animals."

This newly discovered worm has provisionally been given the snappy title "Emits Yellow Muscus A"

British nature lovers who like the idea of making their mark on taxonomy might be missing a trick as, according to the Natural History Museum, "small, less easy to identify organisms will no doubt turn out to be new species to Britain and even to science".

For example, a new species of beetle is discovered in the UK about once a decade, says Max Barclay, senior curator at the museum.

Quedius lyszkowskii Lott and Mirosternomorphus heali Bercedo & Arnaiz were the last two to be found, in 2010, in Kent and parts of Scotland.

You might also like:

Dr David Agassiz wrote the original paper on a pale grey moth with brown speckles, Prays peregrina, first discovered in London in 2003.

It has since been spotted in Cambridge, Kent and Sussex, but there are no records of it anywhere else in the world, he says.

"Either they must be breeding locally or else emerging from imported plant material or foodstuffs," he adds.

But he says the lack of records from any other country is "surprising" and the fact they were not found prior to 2003 is "puzzling".

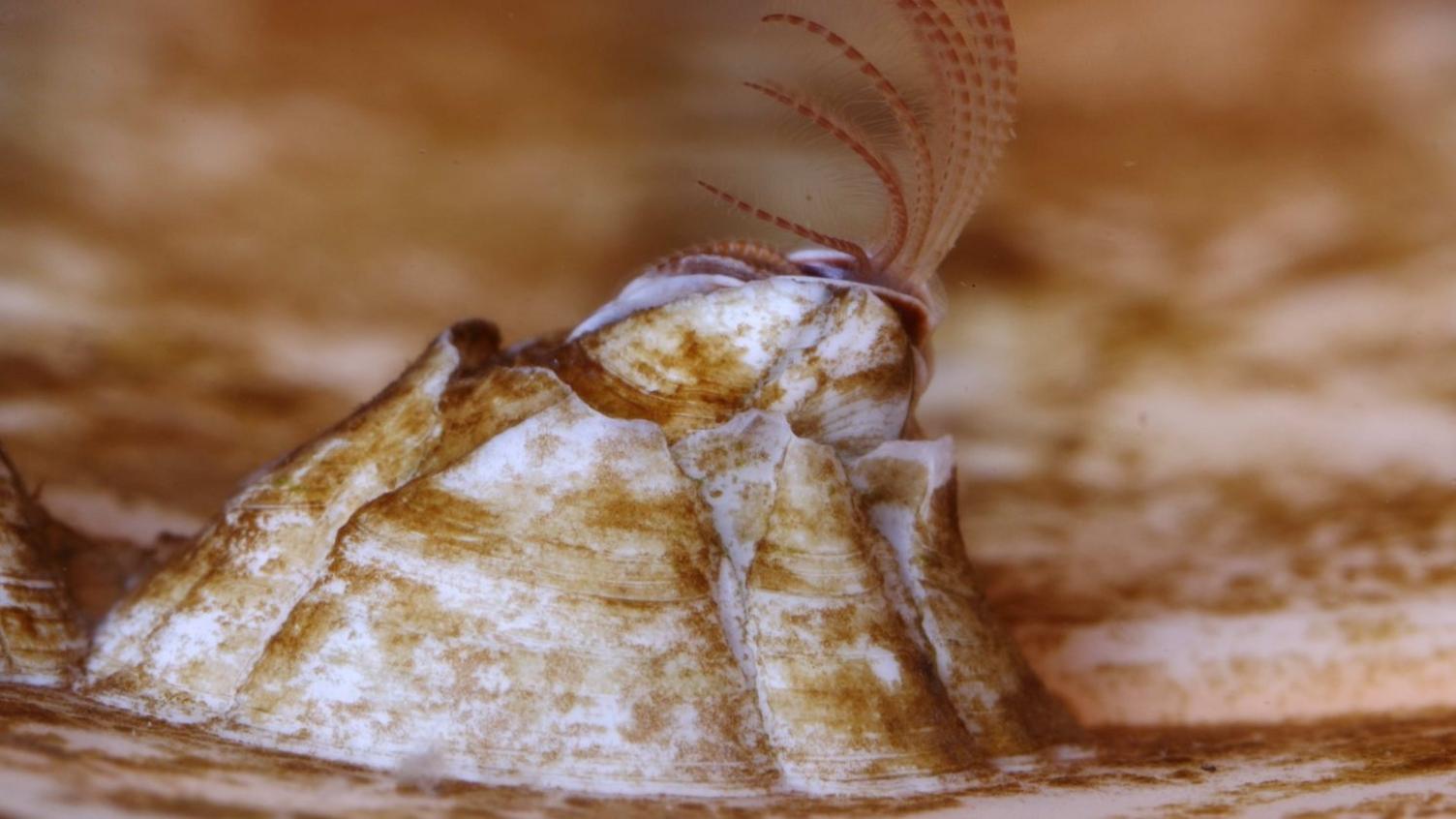

Goose barnacles are among the crustaceans from US waters that Mr Trewhella has found on the Dorset coast

This pale grey moth with brown speckles was first discovered in London in 2003

In 2014, Dr Andrew Polaszek published the description of a new species of parasitoid wasp.

These delightful creatures lay their eggs on or in other insects, which are then eaten alive by their larvae.

The wasp, Encarsia harrisoni, was found in a school playground in suburban Sevenoaks, Kent.

It was one of the first new UK species to be confirmed using DNA sequencing technology, Dr Polaszek says.

Mirosternomorphus heali Bercedo & Arnaiz (left) and Quedius lyszkowskii Lott are the most recently discovered species of beetle in the UK

David Fenwick, who produces photographic wildlife identification guides of marine life, recently unearthed a worm in Penzance, which he provisionally gave the snappy title "Emits Yellow Muscus A".

It's related to Eulalia clavigera - the common green leaf worm - which is found on rocky shores but emits a clear, rather than yellow mucus, he says.

He argues we could be discovering many more new-to-science species, but they're not deemed "commercially important".

"If a species was important for cod, for example, it might get supported but, sadly, small microscopic, obscure species are largely being left in obscurity."

New plant life is also being identified - this seaweed was collected in Devon last month by National History Museum researcher Prof Juliet Brodie

As well as those species that were previously unknown to science, others are new introductions to Britain or haven't been seen for a while, the Natural History Museum's identification team says.

Mr Trewhella is a dab hand at finding creatures such as tropical worms, crustaceans and molluscs that have made it to our shores from overseas on plastic - which he describes as an "artificial conveyor".

"Some objects can be a real treasure trove. I found six new species to northern Europe on one little polystyrene buoy the size of a football," the 54-year-old says.

He's also found bugs that haven't been seen in the UK for a long time, including a 2mm springtail he collected on the seaweed-strewn strandline at Chesil Fleet in 2016 that hadn't been recorded in the UK for 34 years.

Goggles with microscope lenses are "a must" when bug hunting

Mr Trewhella keeps many of the creatures he finds in tanks at home so he can study them - luckily for him his wife is a marine biologist.

It's particularly important that we learn more about species coming to the UK from abroad, Mr Trewhella believes.

"It's speculative at the moment but as our seas potentially warm due to climate change, then there's a possibility that these animals could break the barrier of being able to survive in our waters, which would potentially be catastrophic.

"Invasive species always have a detrimental effect, no matter what size they are.

"Just look at the effect grey squirrels have had on our reds and the introduction of the rhododendron that has strangled our native trees and plants."

Encarsia harrisoni larvae inside a whitefly (above) and an emerged adult

He says his main aim is "to inspire others to get out and engage with the natural world".

"We are in danger of assuming we know everything and have found all the animals that occupy the planet, but of course this is not the case.

"New species are found quite often and genetic work is rewriting many classifications of ones we are familiar with," he says.

"It doesn't have to be new or rare, it's just about understanding why things are there, the role they play and what would happen if they did not exist.

"Once you sit back and just observe, it all starts to make sense."

- Published17 April 2018

- Published19 November 2017

- Published29 November 2016

- Published28 September 2016

- Published12 July 2016

- Published20 May 2016

- Published22 January 2014

- Published23 August 2011