Nighthawking: Metal detectorist explains why he broke the law

- Published

The practice of nighthawking is shrouded in secrecy, few metal detectorists will admit to doing it

A metal detectorist has explained why he broke the law to go "nighthawking" on private land in search of buried treasure.

Peter, from Southampton, used to go out at night two or three nights a week until he stopped during the pandemic.

Dorset Police said so-called "nighthawking", or illegal metal detecting under the cover of darkness, had recently caused damage to farmland.

And Mark Harrison from Historic England said it was "stealing our past".

Peter has been metal detecting for 18 years, and said he only gave up going out at night after a famer gave him permission to search on his land.

He said: "I don't do it very often but it's a real buzz, it's pitch black and you're stumbling all over the place in the middle of nowhere.

"But you've got to keep it close to your chest, where you've been, what you've found."

Experts have said this secretive nature is why the theft of archaeological artefacts by metal detectorists can be a hard crime to quantify.

But a study by Oxford Archaeological for English Heritage in 2009 found 226 out of 240 archaeological sites identified had been targeted.

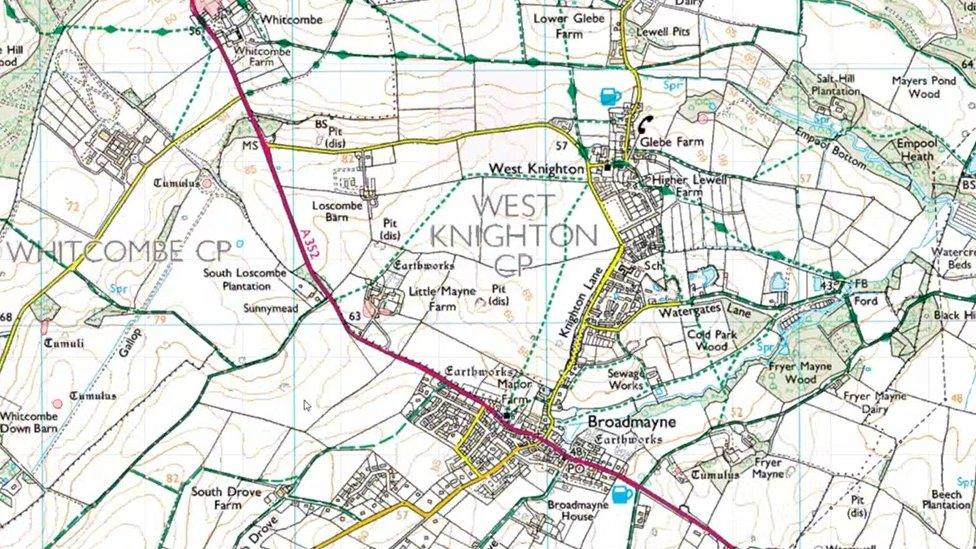

Historic battlefield sites are often places of interest, but farmland can also be targeted, such as a recent case in Dorset at an East Knighton farm.

Historic England: there are over 500,000 protected sites in England alone

Tim Merry, who manages the Dorset farm, said there were "lots and lots of holes" which had been dug in the two newly-planted maize fields.

He said the damage was not made by animals: "I've seen it before, I've seen the footmarks. It's deliberately reckless and they don't cover their tracks.

"It's not the crime of the century but it's unacceptable," he said, and added that the farm had fallen victim to nighthawkers before.

Mark Harrison, Historic England's head of heritage crime strategy, said: "The area's within a rich, historic landscape with stone circles and archaeological burial mounds."

Mr Merry, who manages 4,500 acres of farmland in the Dorchester area, said he never gave permission to metal detectorists to search for treasure on his land.

There were "lots and lots" of holes according to Tim Merry, manager at the East Knighton farm

Peter, 64, said on one occasion while nighthawking he had been threatened by a farmer with a gun, and added that his finds over the years had not made him rich.

"I found a gold ring once, a roman brooch, buckles, but never any gold coins," he said.

"I used to keep it but I met a collector and cashed it all in and paid off my rent arrears. Everyone thinks it makes you rich, but it doesn't.

"Once I fell into a four foot deep ditch and nearly broke my back, you're working blind see, you can't have a light on."

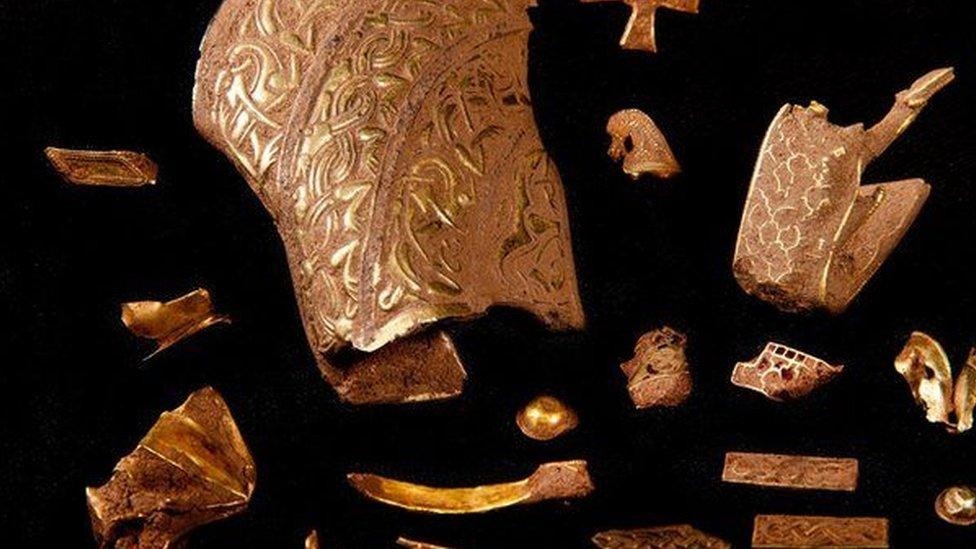

Some of the thousands of fragments from the Staffordshire Hoard, discovered in a field

Historic England's Mr Harrison, said he does not like the term nighthawking.

"It almost romanticises it, but they're stealing artefacts that belong to all of us," he said.

"Say the Staffordshire Hoard had been taken by a thief, they may have made some money but we would have lost all that knowledge."

He said as a nation we are fascinated by our history and "the passion for the past is enormous".

"Every year around 75% of adults visits a heritage site, that's something we have to preserve for these and those that follow," he said.

But Mr Harrison said the majority of detectorists were law-abiding and reported their finds.

"I'm impressed by their determination and patience. I haven't met anyone that says 'I'm out to make a lot of money.'

"They're proud of what they've found, however, there's a small minority who are intent on stealing our past," he added.

And Peter said he had quit nighthawking after lockdown and the pandemic: "It was addictive, I'm glad I'm out of it now, but it's proper adrenalin living on a knife edge, like being on a tight-rope."

Follow BBC South on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, or Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to south.newsonline@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published5 July 2019

- Published12 July 2015