Deadly animal markings offer clue to fear of holes

- Published

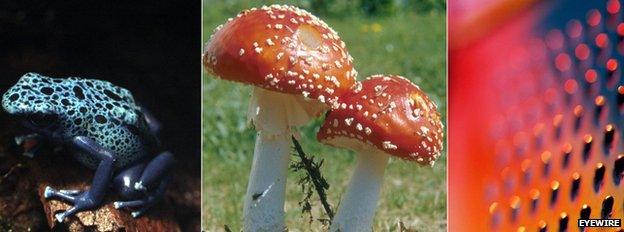

Professor Arnold Wilkins (l) and Dr Geoff Cole have found trypophobia - the fear holes - is triggered by images in the brain which feature 'high contrast at mid range spatial frequencies'

Trypophobia is the fear of holes - a condition that scientists at the University of Essex believe nearly 20% of people might have. But could the phobia, in which sufferers are put into a cold sweat by aerated chocolate, be explained by a latent fear of deadly animals?

Dr Geoff Cole was 13 years old when he had his first trypophobic episode.

He was at school in a metal working class when a friend drilled holes in a ten pence piece.

He turned to Geoff and showed him the perforated coin - a sight that made him feel nauseous. So much so that he had to sit down.

He is now a vision scientist working in the centre for brain science at the University of Essex.

The office next door belongs to Professor Arnold Wilkins, one of the world's leading experts in visual stress.

Prof Wilkins had never heard of trypophobia until Dr Cole told him what it was, and that he had the phobia.

Prof Wilkins says knowing why poisonous organisms use trypophobic patterns would be an exciting research area

For trypophobes, the sight of clusters of holes in various formations can cause unpleasant reactions - from discomfort to debilitating panic attacks, hot sweats and an increased heart rate.

But holes are not the problem. The cause of trypophobia lies in the brain's understanding of what it is seeing.

In the case of aerated chocolate or a cheese grater, the brain is seeing high contrasts between light and dark repeated a certain number of times within a given field of view.

Before Dr Cole and Prof Wilkins published their paper, there had been little scientific investigation into the condition.

Publication of the paper garnered a good deal of media attention, most of it focused purely on the existence of the condition.

Of less interest, said Dr Cole, were its findings as to a possible explanation of the phobia.

"A big clue to this came from a trypophobic person I know who visited and said they had found a trypophobic animal - the blue ringed octopus," said Dr Cole. "I went to Prof Wilkins and said we needed to analyse poisonous animals.

"One part of the brain sees, say a seed pod of a flower. But another part of the brain says I've done spectral analysis and that's a poisonous animal, you need to be careful.

"It doesn't matter that our rational side knows, the fact is the other side of the brain is winning.

"We all know that flying is the safest form of travel but that just doesn't win for some people when they're taking. Trypophobia is a lot like that."

So what is happening inside the tryphobic brain when it sees soap bubbles or a cheese grater?

"Well," said Dr Cole, "Prof Wilkins and I took trypophobic images and broke them down into their fundamental units meaningful to the visual system, things like wavelength of light, contrasts, edges, lines - the building blocks with which we see the world.

"We found that the images had a particular visual signature and when you analyse images with certain spatial frequencies you find that images from the natural world have a particular visual signature which can be represented on a graph.

"But trypophobic images have got a different signature on the graph.

"Their defining signature is high contrast at mid range spatial frequencies. This means the images tend to contrast between dark and light about three times per centimetre at arms lengths.

"Images in the natural world just don't have this characteristic apart from one class of objects and that's dangerous animals."

The deadly blue ringed octopus sparked the idea that dangerous animals and trypophobic images might be linked

Dr Cole says trypophobia may well be "the most common phobia people have never heard of".

"We determined that about 17 or 18% of the population had trypophobia - we worked that out from showing people a mix of trypophobic and other images and asked how they felt viewing them.

"What we really think is that everybody is trypophobic, but it is just a matter of degree, rather like autism.

"There are a range of images that induce an aversion. But most often they feature a cluster of holes when looked at from reading distance are about two or three mm wide clustered together.

"The most common example is the lotus seed pod. The head is full of holes. Its the one image people really don't like.

"It's a flower so it should be nice. But to many people it just isn't nice."

The impact of a trypophobic experience can be severe. Dr Cole has come across people so distressed by seeing something that they have been off work for two days.

That degree of distress is something Dr Cole says he too has felt.

But immersing himself in his study of trypophobia - and the various images he has asked others to gaze at - Dr Cole believes he is, if not 'cured', at least de-sensitized.

Although he still understands why certain images are trypophobic, he finds them less so now.

Prof Wilkins has subjected trypophobic images to mathematical scrutiny and says he can now predict with a degree of accuracy which images will generate a trypophobic response.

"We now know why the images are uncomfortable," said Professor Arnold Wilkins. "We are not quite sure why it is that poisonous animals use these characteristics.

"That's an another exciting avenue of research."

- Published26 November 2013

- Published18 October 2013