Benjamin Lay: The Quaker dwarf who fought slavery

- Published

Benjamin Lay was a pioneer of non-violent direct action

He stood only about 4ft (1.2m) tall, yet what Benjamin Lay lacked in stature he made up for in moral courage and radical thinking. He was a militant vegetarian, a feminist, an abolitionist and opposed to the death penalty - a combination of values that put him centuries ahead of his contemporaries.

For the hunchbacked Quaker was not a product of the 1960s counter-culture but of the Essex textile industry of the early 18th Century. The BBC charts the achievements of an extraordinary man, from his early life in eastern England, to the sugar plantations of Barbados and the British territory that would become the USA.

In September 1738, six years after arriving in America, Lay went to the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of Quakers with a hollowed-out book inside of which was a tied-off animal bladder containing red berry juice.

You might also like:

Lay told the gathering, which included wealthy Quaker slave-owners: "Thus shall God shed the blood of those persons who enslave their fellow creatures."

He then plunged a sword into the book and the "blood" splattered on the heads and bodies of the horrified slave-keepers.

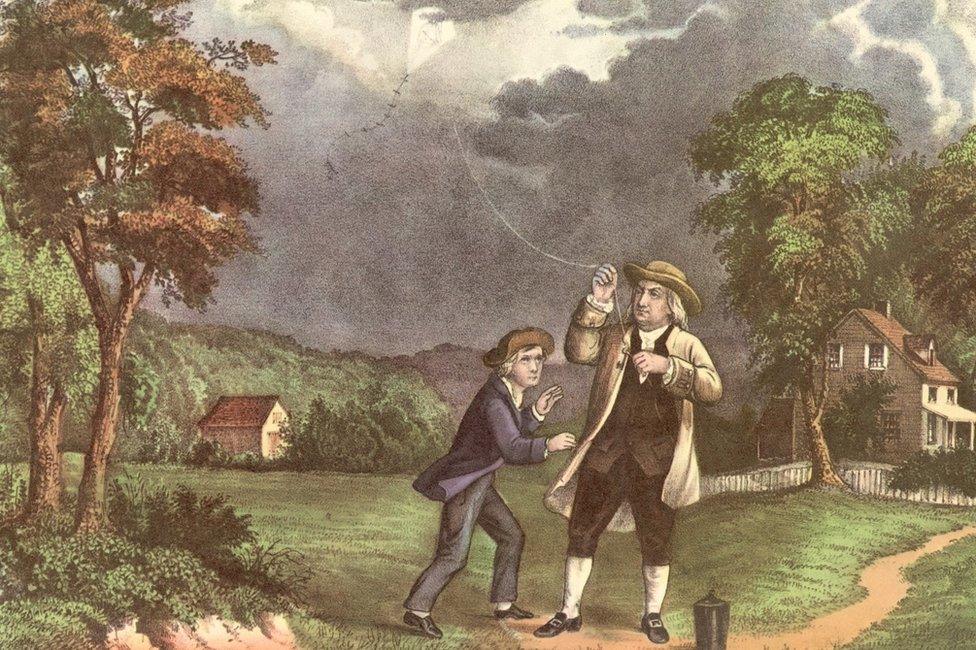

The polymath and statesman Benjamin Franklin, depicted here conducting an experiment to prove lightning was electricity, befriended Lay and published his work

As his biographer, University of Pittsburgh historian Marcus Rediker, external, says: "He did not care whether people liked it or not.

"He wanted to draw people in; he was saying: 'Are you for me or against me? Are you for slavery or against it?'

"He lost the battle with the elders of the church but won it with the next generation."

Lay's journey to become perhaps the most visionary radical in pre-Revolutionary America - he was one of the first people to boycott slave-produced products, in the same way campaigners today shun products made in sweat shops - began near Colchester in England.

Born in 1682 in Copford, he trained as a glove-maker in Colchester which had a major local textile industry and was a hotbed of radical thought.

"He was a third-generation Quaker from an area with a strong history of religious radicalism," said Dr Rediker.

He later became a sailor, and his experiences were to shape his views on slavery.

Lay found senior Quakers keeping slaves in 18th Century Philadelphia

"Lay first learned about slavery through hearing stories from his sailor friends, some of whom may have been slaves themselves," the historian said.

"There was also a radical seafaring tradition, a sailor's ethic of solidarity, which connects in Lay to the radical tradition."

After returning home to the Colchester area, Lay found himself in trouble with the Quaker community because he felt the need to speak out against those who fell short of his high moral standards.

"He was a troublemaker at every moment of his life," said Dr Rediker.

"He had a powerful sense of his convictions and would speak truth unto power."

Lay made his own clothes from flax to avoid the exploitation of animals

From Colchester he went to Barbados with his wife Sarah Smith, also a Quaker and a dwarf, to open a general store, but his experience "was a nightmare".

"It was the leading slave society of the world," said his biographer. "He saw slaves starved to death, he saw them beaten to death and tortured to death, and he was horrified,"

The Quaker spoke out against the plantation owners and, angered, they told him to leave.

Lay's odyssey next took him to Philadelphia, where he befriended the polymath Benjamin Franklin, a future Founding Father of the USA, who would publish Lay's book, All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates.

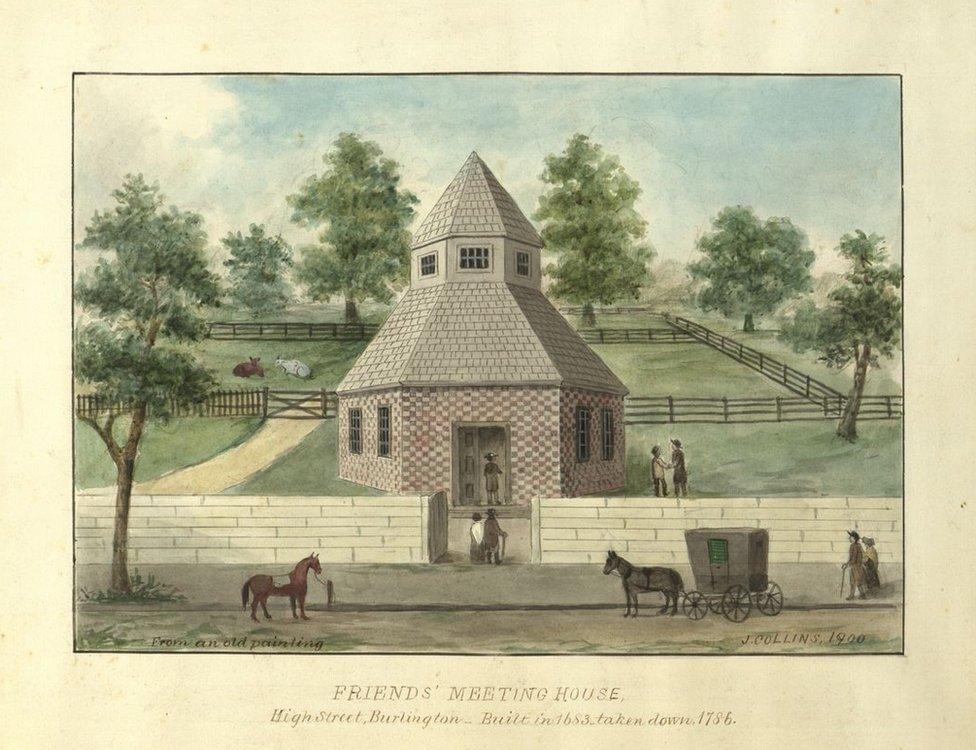

The Friends' Meeting House in Burlington, New Jersey, was one of the places where Benjamin Lay protested

While in America, he continued to defy conventional wisdom.

Lay crafted his own cottage in a cave, lining the entrance with stone creating a roof with "sprigs of evergreen", said Dr Rediker.

His home was apparently quite spacious, with room for a large library. Lay also planted an apple tree and cultivated potatoes, squash, radishes and melons.

Lay's favourite meal was "turnips boiled, and afterwards roasted", while his drink of choice was "pure water".

The committed vegetarian made his own clothes from flax to avoid the exploitation of animals - he would not even use the wool of sheep.

Lay is thought to have made his home in this cave

His moral certainty meant he could not allow the slavers in his midst to go unchallenged, and he would often attend Quaker meetings to denounce slavers.

Dr Rediker said they "flew into rages" when Lay spoke out against slavery.

"They ridiculed him, they heckled him... many dismissed him as mentally deficient and somehow deranged as he opposed the 'common sense' of the era," he said.

He was during his long life disowned by the Abington Quakers in Pennsylvania, as well as groups in Colchester and London.

In November 2017, almost 300 years after his denunciation, the North London Quakers recognised the wrong they had done in their treatment of Lay, accepting the group had "not walked the path we would later understand to be the just one".

"It has righted an historical injustice," London Quaker and writer Tim Gee said.

In 1758, the year before Lay died aged 77, the Philadelphia Quakers ruled they must no longer take part in the slave trade.

"Lay understood from this that it was the beginning of the end," Dr Rediker said.

The Quakers would go on to be at the forefront of the campaign against slavery, which would ultimately be abolished in the US in 1865.

For Mr Gee, Lay's lasting legacy is that he had "a vision for a better world".

"He could see basic injustices in society which were seen as normal and dragged the injustices into the light."