Infected blood scandal: The ordinary people in a 'horrific nightmare'

- Published

Jackie Britton, Melanie Walters-Richmond and Alan Vickers all provided evidence to the inquiry

With the end of the Infected Blood Inquiry just four weeks away, BBC South reunited three people impacted by the scandal to hear how it's affected their lives.

"Nobody looked for us, nobody found us and nobody treated us," said Jackie Britton, a 62-year-old from Fareham, Hampshire.

She is one of the 30,000 people infected by contaminated blood products during the 1970s and 1980s. Blood products were imported from the USA, much of them sourced from high-risk donors like prisoners and drug users.

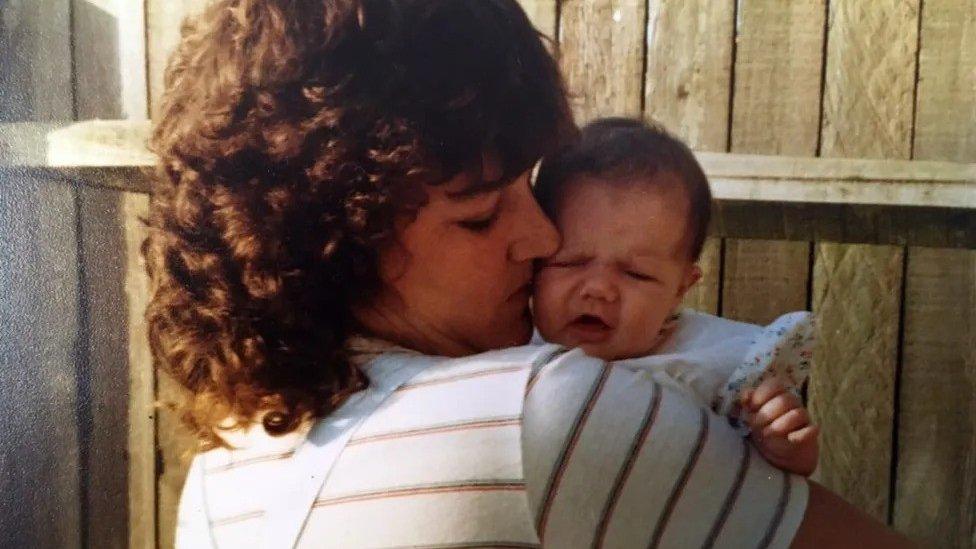

Jackie contracted Hepatitis C in 1983 after receiving a blood transfusion during childbirth. It took nearly 30 years for her to be diagnosed after decades of ill health.

The potentially fatal virus attacks the liver, which can result in cirrhosis and cancer.

Melanie Walters-Richmond, 52, from Farnham, was infected with hepatitis C in 1989 after receiving the blood product Factor VIII.

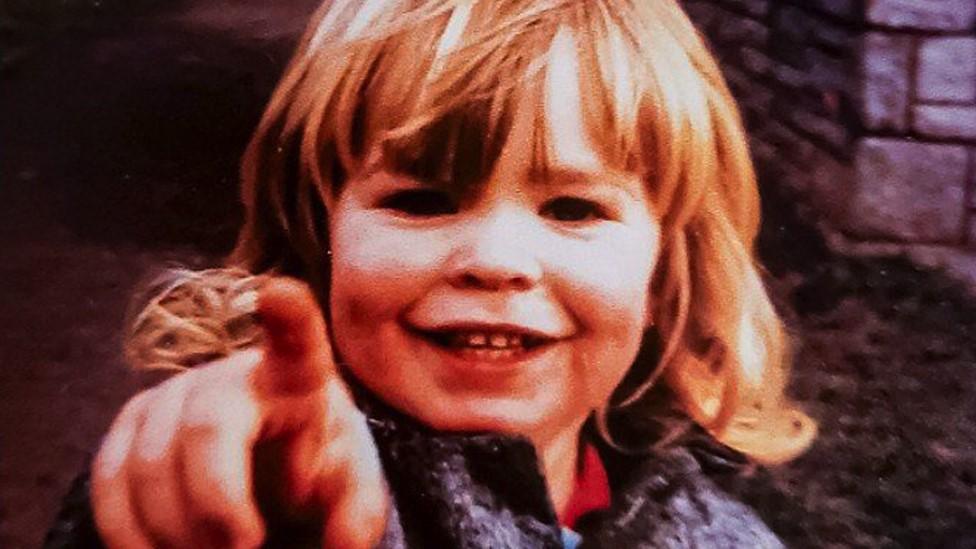

Sally Vickers is one of 2,900 people thought to have died as a result of the scandal

She wasn't told of the diagnosis until 1992, when a doctor told her to make sure her tissues from a nosebleed went into a separate bin, "because you've got hepatitis C".

Alan Vickers, 66, met his late-wife Sally in 2004, just six months before she was also diagnosed with hepatitis C, contracted from a blood transfusion in 1981.

He said Sally tried to push him away, telling him: "you might as well go because I ain't going to live long." Instead, Alan proposed that day.

After years of debilitating health effects, on a Wednesday morning in 2017 Sally was told she had cancer, caused by long-term damage of hepatitis C. By Friday she had passed away.

Sally is one of the 2,900 people thought to have died as a result of the scandal.

For Jackie, Melanie and Sally there was chronic fatigue, health complications, lost work opportunities and for some, marital breakdowns.

Jackie Britton contracted hepatitis C in 1983 after receiving a blood transfusion

"Your whole life gets turned upside down", said Jackie. "Two o'clock in the morning and you're planning your own funeral".

Even the joy of childbirth was tainted for Melanie, when an hour after her son's birth she said a doctor told her: "Your baby is beautiful, it's just sad you're never going to get to see him go to school."

After years of campaigning, a UK-wide inquiry into the scandal was announced in 2017.

It was led by former judge Sir Brian Langstaff, and took evidence between 2019 and 2023.

Melanie Walters-Richmond was infected with hepatitis C in 1989

Jackie, Melanie and Alan all provided evidence to the inquiry.

"I can remember walking through the front doors and seeing everybody, and it was the first time I felt like I belonged somewhere", said Melanie.

Jackie said the inquiry made her feel "listened to" and "heard", while for Alan it was an opportunity to meet other bereaved people.

The inquiry will publish its report on 20 May, delayed by half a year due to the time needed to prepare "a report of this gravity".

Those infected have received annual financial support from the government, but a final compensation deal has not been agreed.

A government spokesperson said: "We have consistently accepted the moral case for compensation, and that's why we have tabled an amendment to the Victims and Prisoners Bill which enables the creation of a UK-wide Infected Blood Compensation Scheme and establishes a new arms-length body to deliver it."

Jackie, Melanie and Alan all provided evidence to the inquiry

For Jackie, Melanie and Alan, the end of the inquiry is a chance to move on from decades of campaigning and trauma.

Jackie would like a national memorial for victims to be created.

"All the names of everybody that died through this scandal needs to be honoured somewhere."

Follow BBC South on Facebook, external, X, external, or Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to south.newsonline@bbc.co.uk or via WhatsApp on 0808 100 2240, external.

- Published18 April 2024

- Published28 February 2024