Rescuers recall missing Lofthouse Colliery miners

- Published

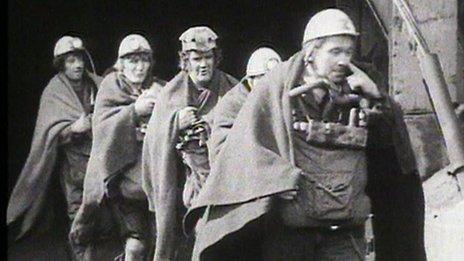

Rescuers worked for six days at Lofthouse Colliery to reach the miners

When seven men died in the Lofthouse Colliery disaster 40 years ago only one body was recovered. And while six men still remain in the mine, the memory of the catastrophe is seared into the minds of those who tried to rescue them.

"I can still see it now in my mind. I can see their faces," recalled 74-year-old miner George Hayes.

He along with a number of others tried to rescue the miners who were trapped hundreds of feet below ground.

Disaster struck in the early hours of 21 March 1973 at the mine to the north of Wakefield.

A group of 30 men were working the night shift in the dirty and dangerous depths of the South 9B seam when it suddenly flooded.

They had cut into an abandoned shaft releasing millions of gallons of trapped, stagnant water.

While 23 men survived, the others simply could not outpace the deluge.

'Run for their lives'

Mining historian and engineer Eddie Downes said: "Water started running on to the [coal] face.

"Initially they were crawling on their hands and knees up to the middle of their thighs and then it started to come into the tunnels at the end of the face.

"The men literally had to run for their lives and this water, sludge, rock and debris chased them for hundreds of yards."

Three hours later Mr Hayes arrived at the pit ready for work - only to be greeted by emergency services.

He said: "I wondered what was wrong. I was hoping it wasn't too bad.

"Then I saw my boss Sid Haigh, whose son was trapped down in the mine, and we went down to rescue the men."

Mr Hayes, along with other members of his "development team", crawled their way through a tunnel above the seam in an attempt to reach the men.

"We were in stagnant water and sludge up to our chest. You couldn't see anything. Our hands were cut.

"It took three or four days before we could get to the air doors and the men were some yards behind that.

A public inquiry found the disaster could have been avoided

"When we were crawling down that's the only time I've been scared in my life. There could've been another inrush of water, you just didn't know what was behind it.

"When we got through I could see something but I didn't know what it was."

In fact, what Mr Hayes had spotted was the body of miner Charles Cotton who had been working alongside his son Terry when the inrush happened.

The pair were able to flee but Charles Cotton struggled to continue and told his son to keep running to save himself.

Out of the seven, the body of Mr Cotton was the only one rescuers could recover.

'Blast of air'

"There's no way rescuers could get to six men," said 70-year-old Tony Banks, who was a so-called 'face overman' at Lofthouse in charge of production.

He was working the night shift in another part of the mine when the disaster struck but was not in danger of the inrush.

"We were just cutting coal as normal and there was a sudden surge of wind, which was most unusual," recalled Mr Banks.

"It turned the ventilation completely round, just for seconds, and everything went silent.

Tony Banks worked in a different part of the mine when the disaster struck but was not in danger

"Then within seconds everything came back to normal - the ventilation blowing the proper way, the banging of the chains and the machinery banging and clanging - as if nothing had happened.

"It was like a dam busting, if you can picture that, and this is why we felt the blast of air.

"In that area where the men were working there were Victorian collieries. There were lots of old mine shafts and tunnels and over the years all these tunnels got completely flooded."

David Hagan was a colliery electrician who was a member of the Allerton Bywater Rescue team, which worked on the rescue mission for six days before it was called off.

"When you go on a rescue operation and then it goes from rescue to recovery, at that point all the blood goes out of your body. Now that was awful, almost soul destroying. That affected me.

"Those six men were never put to rest. They're still down there.

"I still think about those men today."

Lofthouse legacy

A fund was set up in the wake of the disaster to support affected families.

A public inquiry followed shortly afterwards and a report was published stating the disaster "could have been foreseen".

The events at Lofthouse left a legacy that changed the nature of how collieries operated and led to the formation of a new safety legislation, The Mines (Precautions Against Inrushes) Regulations 1979.

The pit closed in July 1981 after the coal was exhausted. The site was later landscaped and turned into a country park where a commemorative stone was erected at the spot above where the miners were trapped.

A new memorial to the dead miners is being built and is expected to be erected in the summer.

- Published19 March 2013

- Published15 March 2013

- Published12 March 2013

- Published9 March 2013