Does Middlesbrough deserve its unenviable reputation?

- Published

The Tees transporter bridge - affectionately known as the "tranny" - remains a symbol of Middlesbrough's industrial heritage

Middlesbrough, an industrial town on England's north-east coast, gets a bad press. It's often near the top of "worst places to live" lists and is currently the worst place in the country to be a girl, according to one report. But, despite the drawbacks, residents - known as "Smoggies" - are determined their home town is somewhere to be proud of.

A row erupted earlier this year over claims easily identifiable doors made refugees targets for hate crime and vandalism, opening locals up to allegations of racism. Statistics about health, drug use and employment make for grim reading.

One person fighting back against the stereotype is BBC presenter Steph McGovern, who says: "I grew up in Middlesbrough and I have the town to thank for what I have achieved in life.

"It gave me a good state education, various jobs in my teens and taught me resilience and independence.

"Quite frankly, I don't think I would be where I am today if I had grown up anywhere else."

Peter says people "wouldn't be so cruel" about Middlesbrough if they understood how hard life can be

Peter, who doesn't want his surname to be used, was born in the town and moved to London for work before returning to look after his elderly parents.

"It's a lovely place to live. To be honest, it's a good job the weather's so bad - otherwise it would be overcrowded," he laughs, before becoming solemn once more.

"Of course, there are some dodgy characters but people are generally friendly. The problem is when people lose their job. Things just spiral.

"The steelworks closed. You see loads more people in the pub now. People who criticise us just don't get it, they don't understand what it's like when the work goes. Your life just spins out of control.

"If people knew what it was like to live like that, turning to drink or worse, they wouldn't have a go at us. They wouldn't be so cruel."

Why Middlesbrough 'can fight back' against negative coverage

BBC News visits...

In a sense, Middlesbrough is a victim of its own success. In 1801, there were no more than four farmhouses marking the territory of the town. After ironstone deposits were discovered in the Eston Hills in 1842, everything changed.

The town, made prosperous by its natural resources and location, mushroomed massively and rapidly.

From being barely a hamlet at the beginning of the 19th Century, by 1860 its population had increased to 20,000. By the 20th Century, there were 90,000 people there, increasing to 160,000 by the 1970s. And there was work for all who wanted it.

But that was then, this is now.

Long, slow industrial decline and the closure of processing plants left swathes of people out of work and Middlesbrough with high levels of unemployment and poverty.

The Office for National Statistics shows unemployment in the North East, external is the highest in England and Wales. In Middlesbrough the unemployment rate is even higher, external than the rest of the region.

Debs thinks there are too many asylum-seekers in Middlesbrough

It's perhaps not surprising the media tend to focus on the negatives.

You could argue the facts speak for themselves.

The townspeople's level of opiate and crack cocaine use is proportionately the highest in the whole country.

More than 40% of private rented housing has been categorised as "low quality" and more than two-thirds of council wards are classed as deprived.

The number of pupils leaving school with qualifications is low.

So we see images of the town taken from the A19 flyover, featuring cooling towers and chemical plants rather than Albert Park, where dogs scamper through the autumn leaves and an impressive fountain burbles.

We see condemned buildings and half-demolished homes rather than the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art or the roomy executive homes of Nunthorpe, Acklam or Marton.

But shoppers braving the rain in Captain Cook Square - named after the locally-born explorer - are fairly impassive about their town's image.

Alan Waters says migrants should be integrated

Doreen Norris, who's lived in the Coulby Newham area for 13 years, says she "doesn't care what southerners think".

"Me and my family know what it's like. They're good people, the people here. Salt of the earth.

"Yes, we've our share of druggies and trouble but it's no worse than anywhere else. I wouldn't leave."

Barbara Cockfield, who lives in neighbouring Marske-by-the-Sea and is in town to do a spot of early Christmas shopping, says drugs are an issue.

"I went to the cinema with my son, and a druggie followed us all the way to the train station. If my son hadn't been there, I'd have been really scared. It is a problem here."

It's an opinion backed up by the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment for Middlesbrough, external (JSNA), which found there are an estimated 21 opiate and crack users per 1,000 people in Middlesbrough. The regional rate is 10 per 1,000 and the national rate is eight.

Support services in the town also have a low percentage of clients who successfully complete drug treatment.

Ray Chambers is one of the long-term unemployed. He hasn't had a job for nearly 15 years.

"There's just nothing to be had," he says, shrugging and wandering away.

There are efforts to revitalise the town. According to the mayor, Dave Budd, there are "great opportunities" for businesses of all types and sizes.

Baker Street was recognised as a Great British High Street, external "rising star" for its independent businesses.

There's a sports village and the town hall is undergoing lottery-funded improvement. Middlehaven, previously an important dock, is being redeveloped into housing, office space and a park.

There is a plentiful pool of potential customers. More than 700,000 people live within a 30-minute drive of Middlesbrough.

Barbara Cockfield believes Middlesbrough has a problem with drug abuse

Legendary football manager Brian Clough is one of the town's most famous sons

But not everyone is keen on welcoming an influx of people.

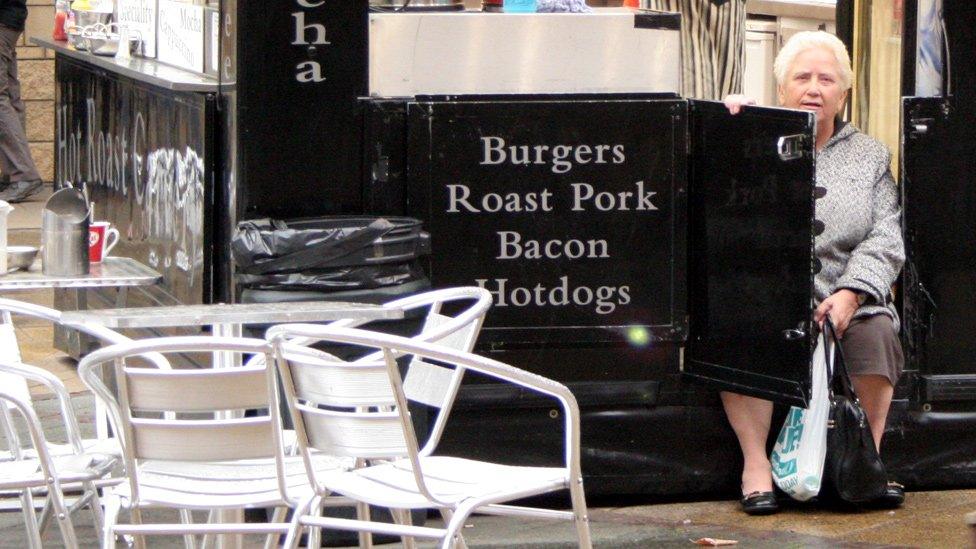

Debs, who works at a hot pork sandwich kiosk in the town centre, says she knows why Middlesbrough is struggling.

"It's the immigrants. We need to get the Asians and the refugees out. They're getting houses before our people, having them furnished and all that.

"We're overrun. They're the trouble. They're very, very rude and they don't speak English."

It's an attitude that chimes with the annual British Social Attitudes, external survey, in which 95% of respondents agreed it was important to speak English to be British.

Is Debs being racist, does she think?

"No. It's the truth. Why do we have to have them?"

Her co-worker agrees. "To me, they're just all foreigners. It was better without them."

No more than one in every 200 of the local population should be an asylum seeker, government guidance says. Middlesbrough is the only place in the UK that breaks that limit, with one in 186.

Analysis of the Annual Population Survey indicates that over the past 10 years, the number of people born outside the UK and living in Middlesbrough has grown from about 6% of the population to nearly 10%.

This growth is largely attributable to an increase in the number of people born in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and Central Asia (the global areas asylum-seekers are most likely to come from).

Alan Waters, 74, who says he's "born and bred Boro", has criticised the number of asylum seekers being housed in the town.

"You know all that fuss about the red-painted doors? Well, I had a solution. Take the doors off completely, then they'd have something to whinge about.

"To be honest, it's not their fault. Of course they have to go somewhere. But it's the people who decided to put all of the non-nationals together. It would be better if they were all spread about and integrated.

"But some areas are being what do you call it? Ghettoised."

Parliament Road in the Gresham neighbourhood is one street where the influx of different cultures can clearly be seen.

A Romanian restaurant is on the brink of being opened. A Polish convenience store and a Middle Eastern mini market share the street with curry houses. Chip shops are selling local delicacy parmo (a flattened slab of breaded chicken, deep fried and topped with white sauce and cheese, served with chips and salad. It was even mentioned in a parliamentary debate, when it was described as "a heart attack on a plate").

Shop windows hold posters advertising English classes and tuition for "life in the UK" tests., external

It's only a couple of streets over from a demolition zone, where the houses still standing have metal shutters nailed over the windows and doors. Mechanical equipment and workmen are on site, turning the remaining buildings to rubble.

A woman with a pushchair hurries past, head bowed against the wind. Kelly was 15 when she had her daughter Shavvaun.

"I'm lucky really. She lives with me mam. I'm lucky my mam could do that. Lots of lasses have their bairns taken away.

"I want the best for her, you know? I had a job in a salon but then it closed. But there's a chance I'll be taken on by someone else.

"I'm on benefits now, but to be honest, that's not the life I want for my kid.

"I'd like to go to college, get some qualifications," she says with quiet optimism.

Kelly isn't unusual. Local teenage pregnancy rates are higher than both the regional and national averages.

But at least Kelly is claiming her benefits.

It's estimated by the JSNA that between 11,500 and 16,300 people in Middlesbrough are not claiming benefits they are entitled to - which it says works out at between £17m and £28m that could contribute to the local economy.

According to Love Middlesbrough, which promotes the town as "a fantastic place to live, learn, work, invest, visit, shop and play", the place is changing.

Investment means the town will be taken "to a whole new level", the organisation says, with new jobs, more leisure opportunities and better homes and schools.

This regeneration might be too late for people like Jay. He's 22 and in a park with three of his friends, where he's trying to scoop some coins out of the fountain.

They're passing around a bottle of cheap vodka and a second one of cola, mixing it in their mouths. It's just after 9am.

"I were in and out of care, didn't hardly go to school. No point, is there?

"You get with a crowd, have a laugh. I don't want a job anyways. Can't do nothing. That isn't going to change, no matter what fancy words people say."

But that's an attitude which doesn't sit well with many others.

Julie Graham, a cleaner whose dog Stella is slurping up fountain water, says the place is "fantastic".

"Even if I won the lottery, I'd stay here.

"I heard someone once say the best thing about Boro was the road out. But that's not true. The best thing is the people. Everywhere you go, there's a friendly face."

Steph McGovern has said: "Middlesbrough people have a fantastic ability to fight back against adversity.

"Whether it's economic hardship or the local football team not doing so well, I love the fact that we adapt, we regenerate and we never give in."

Middlesbrough is twinned with Dunkirk. And maybe a fighting spirit is just what the town needs to get back on its feet again.