David Oluwale's death in 1969 helped 'reshape Leeds'

- Published

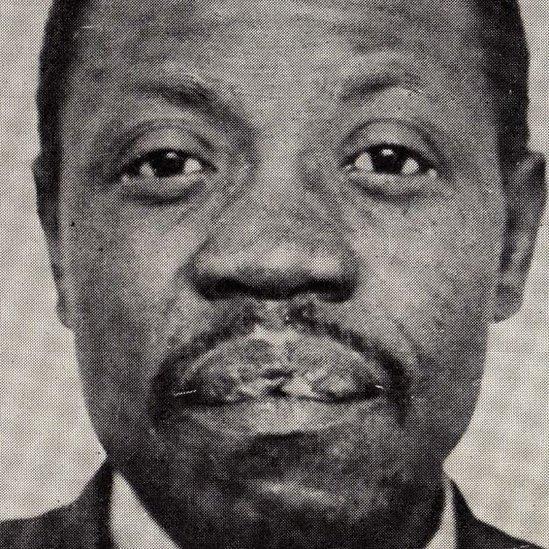

Artist Rasheed Araeen created an image of David Oluwale which features in the exhibition

A British Nigerian man who was "hounded to his death" by police in Leeds is being remembered in a series of events to mark 50 years since he died.

David Oluwale was last seen fleeing two police officers on 18 April 1969 and later found drowned in the River Aire.

His death led to the first prosecution of British police for involvement in the death of a black person.

Max Farrar, from the David Oluwale Memorial Association, said his tragic story had helped change the city.

Among the events, external was a gathering at Killingbeck Cemetery, where Mr Oluwale is buried alongside nine other people in a pauper's grave.

The gathering at David Oluwale's graveside was a contrast to the lonely burial he had in 1969 when the only person to attend was a vicar

An exhibition by artist Rasheed Araeen is being held at The Tetley gallery in Leeds while other events through April include poetry readings, music performances and a walk round Leeds of places associated with Mr Oluwale's life.

Who was David Oluwale?

Born in Lagos in 1930, Mr Oluwale migrated from Nigeria in August 1949, hiding on board a cargo ship destined for Hull.

Because Nigeria was a British colony, he was able to obtain a British Travel Certificate and so left behind his poverty-stricken home in search of a better future.

He was too poor to buy a ticket for his journey and so crept on board the Temple Bar ship, hiding among the boxes of groundnuts being delivered to the port city.

But he was discovered a few days into the journey and, as soon as the ship docked, was jailed for being a stowaway.

Upon his release, Leeds was the place where Mr Oluwale spent most of his English life.

The exhibition at The Tetley art gallery features press clippings and a scrapbook made by the whsitle-blowing police cadet

According to Mr Farrar, he had a lot of friends among the small group of West Africans in the city at the time and his social life revolved mainly around the old Mecca ballroom and the former King Edward Hotel.

He worked in industries helping rebuild the post-war city, with friends recalling him as a popular and easygoing.

What happened to him?

In 1953, Mr Oluwale became involved in a fight with police and it was rumoured he took a truncheon blow to the head.

He was charged with disorderly conduct and sent back to prison where it was reported he suffered from hallucinations, possibly from the injury suffered during his arrest.

He was labelled as a schizophrenic and sent to Menston, an asylum outside Leeds, and did not resurface for eight years.

At Menston, Mr Oluwale was treated with electric shock treatment and heavy antipsychotic tranquillisers and upon his release was unable to hold down a job and quickly became homeless.

He spent the final two years of his life sleeping rough in the city centre, where he was the target of routine mental and physical abuse at the hand of two police officers, Insp Geoffrey Ellerker and Sgt Kenneth Kitching.

The last sighting of Mr Oluwale was in the early hours of 18 April 1969 when he was seen being chased by the officers towards the River Aire. His body was found in the water two weeks later.

Police treatment

In 1970, police cadet Gavin Galvin reported he had heard police station gossip about the way Kitching and Ellerker had treated Mr Oluwale.

An inquiry was started and evidence gathered to prompt manslaughter, perjury and grievous bodily harm charges against the officers.

During the trial in November 1971, a catalogue of sustained physical abuse came to light, at the hands of the pair.

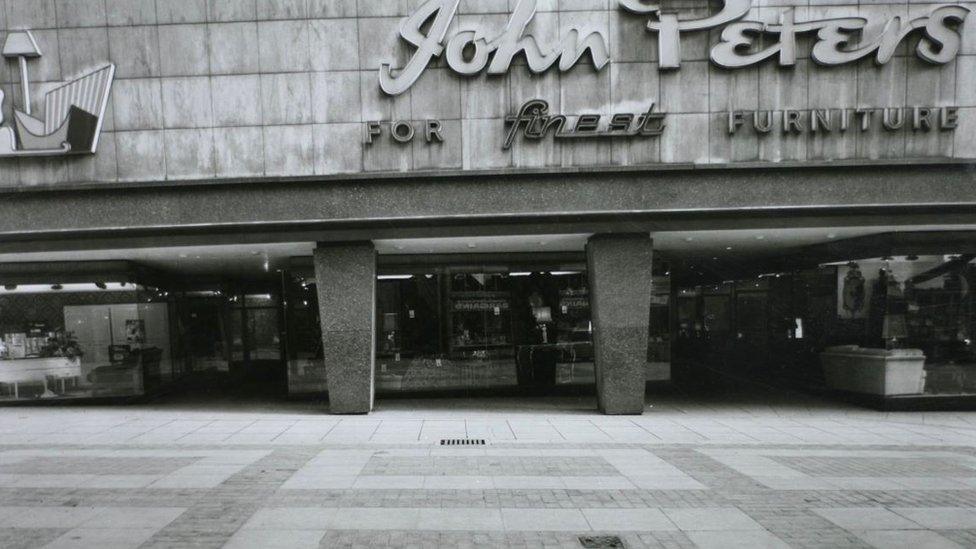

David Oluwale was known to sleep in shop doorways, including the entrance to the former John Peters Store on Lands Lane

The court was told both officers, who worked together at Millgarth police station, made it their business to make life unpleasant for Mr Oluwale because they "simply did not want him in the city".

It became well known at the station that whenever he was seen in Leeds, a message had to be passed to either officer so they could attend to it.

It was found racist terms were used on paperwork relating to Mr Oluwale, such as a racial slur being scribbled in the space reserved for nationality on his charge sheet.

But, despite that, there was no mention of racism during the trial.

The officers were jailed for a series of assaults but found not guilty of manslaughter on the direction of the judge.

The trial received national coverage but justice and civil rights campaigners considered it a whitewash, presenting a deliberate negative portrait of Mr Oluwale as a "social nuisance".

The aftermath

Highly invisible for most of his English life, upon his death Mr Oluwale entered popular culture in the city and became somewhat of a folk hero.

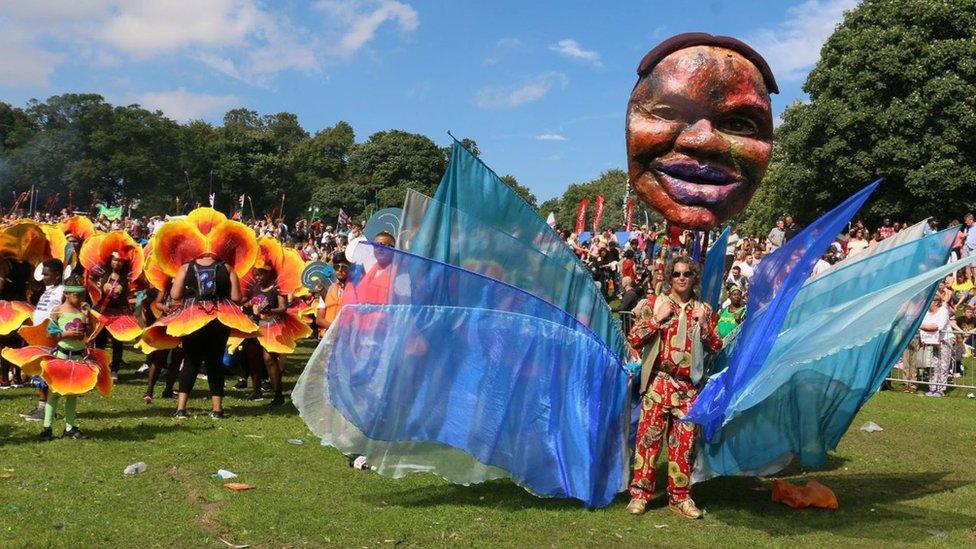

David Oluwale was celebrated and transformed into a carnival king at the Leeds West Indian Carnival in 2017

The words Remember Oluwale were written on Chapeltown Road in huge white letters for most of the 1970s.

Mr Farrar said the case led to police in Leeds working with the United Caribbean Association on the Leeds Scheme, a pioneering effort to breach the gulf between black people and the police.

The discovery of declassified police paperwork relating to the case led to a book being written in 2007 by Kester Aspden, The Hounding of David Oluwale, which was adapted into a stage play first performed at West Yorkshire Playhouse.

Soon after that the David Oluwale Memorial Association was born, with the intention of educating people about his story and creating a permanent memorial to him.

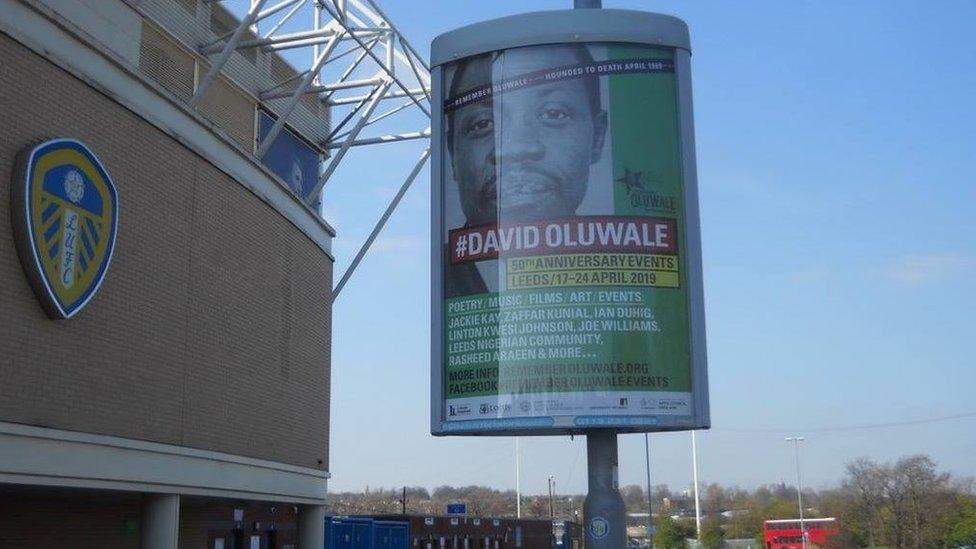

Posters have been put up around the city to highlight the events planned

"David's is a formative story about post war Leeds," Mr Farrar said.

"We had these tragic circumstances of how he was systematically abused and died and then we see a transition to a more inclusive, hopeful city.

"Thankfully a lot has happened in 50 years. Lessons have been learned and Leeds has improved provisions for all the problems that David endured."