Spalding shooting: 'Vital' to spot controlling behaviour, says review

- Published

'From the outside, we were a normal family'

A report into a father who shot dead his wife and daughter has said it is "vital" for all professionals to recognise signs of coercive control.

Lance Hart, 57, killed his wife Claire, 50, and daughter Charlotte, 19, before killing himself, in Spalding in 2016.

A council-led domestic homicide review, external has recommended staff training and a public awareness campaign.

Hart's sons, Luke and Ryan, said there were "potential opportunities" for GPs and other agencies "to step in".

Claire Hart and her children Charlotte, Luke and Ryan were unaware they were being coercively controlled by Lance Hart

Ryan and Luke Hart are trying to raise awareness of coercive behaviour

Safer Lincolnshire Partnership's review detailed how Mrs Hart and her three children had been suffering from coercive control abuse by her husband for many years without them realising.

Hart shot the pair with a single-barrel shotgun in a swimming pool car park before turning the weapon on himself.

The murders happened days after Mrs Hart had left the family home following a breakdown in the couple's marriage.

Hart's behaviour was not known to professionals or understood by members of his family, the report said.

But health records showed Claire, Charlotte and Lance had a number of illnesses, with Hart having been prescribed anti-depressant drugs.

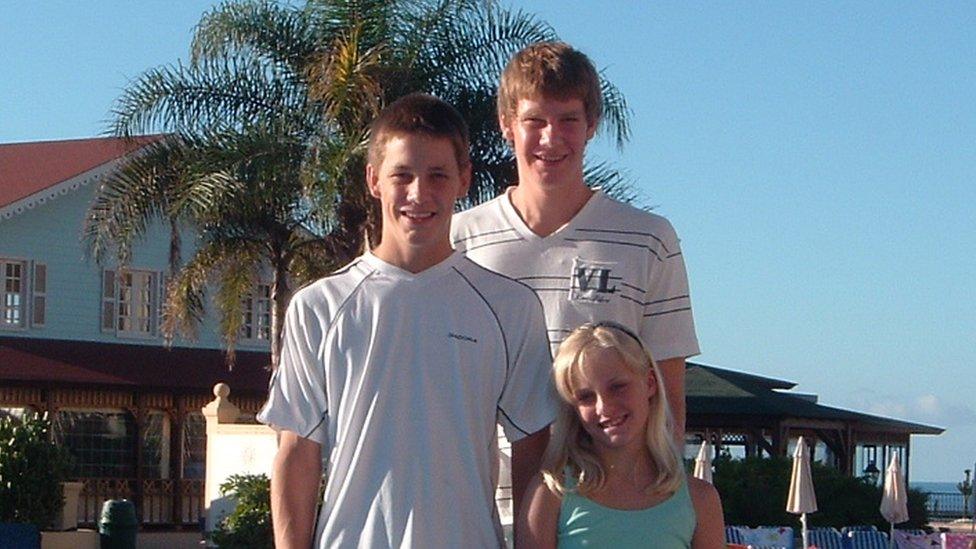

Brothers Luke and Ryan, with their sister Charlotte Hart

The review said that Mrs Hart told her GP a month before her death that pain from a facial condition she was suffering from had become worse due to "some marital stress".

But as she did not "indicate any domestic abuse or fear of domestic abuse", her GP had not questioned it further.

As a result, the report also recommended health professionals should question patients more about domestic abuse.

"This means it is vital for all professionals to be able to recognise the criminal cases of Coercive and Controlling and respond to them - as the victims themselves may not either see themselves as victims or be physically unable to break free," the report said.

Luke and Ryan Hart say domestic abuse, in the form of coercive control, is not fully recognised by members of the public or authorities

Ryan Hart told the BBC: "No one knew what to look for... unfortunately it was missed by us and we lived it."

His brother Luke said: "We were living a personal hell and our father was dangerous."

"I think a lot of people felt afraid of asking us what was going on because of the fear our father cultivated, especially around our close family. They were all afraid of helping us because of that fear."

Luke with his sister Charlotte

Coercive control became a criminal offence in 2015.

Sandra Horley, from domestic violence support charity Refuge, said police and other authorities "were having difficulty gathering evidence because they don't really understand what coercive control means - and this is across the board".

"They haven't had sufficient training to understand the complex dynamics of domestic abuse which doesn't have to involve physical abuse," she added.

A Home Office spokesperson said it would "continue to work with police and prosecutors to ensure the laws are used to maximum effect".

- Published10 December 2017

- Published1 June 2017

- Published16 August 2016

- Published27 July 2016

- Published20 July 2016

- Published21 September 2016

- Published18 February 2017