The rise and fall of the GLC

- Published

It is 30 years since one of the most controversial experiments in local government was scrapped. What was the Greater London Council (GLC) and how has it shaped today's politics?

If you wander along the Thames to Westminster Bridge and look across the river you will be confronted with the imposing sight of County Hall, with its curved frontage, Ionic columns, porthole windows and flagpoles.

Now, it houses two hotels and several tourist attractions: the London Aquarium, London Dungeon and an amusement arcade.

But beyond them, in the belly of the building, is a chamber intended for political debate. Leather benches and a speaker's chair lie behind locked doors, gathering dust.

This was where, from 1965 to 1986, members of the GLC met and attempted to confront the biggest problems facing the capital: a burgeoning population, a strained transport network, polluted streets and inadequate housing.

It began as an effort to rationalise London-wide planning, and it ended in a fierce face-off between two of the most popular and divisive figures in British politics: Margaret Thatcher and Ken Livingstone.

Although the GLC met for the last time 30 years ago, its influence on the current political landscape can still be felt in the idea of the Northern Powerhouse, in the fight for the London mayoralty and in the rise of Jeremy Corbyn.

Why it was created

London in the 1950s could be a grim place. Large swathes of residential streets remained derelict after being bombed out during the war and the houses still standing were often squalid and overcrowded. Thick fog hung over the city and roads were dirty and dangerous.

The rise and fall of the GLC

The city had begun to sprawl far beyond the boundaries of the London County Council (LCC), the Victorian-era body which had been set up to oversee it.

According to Joseph Sparks, Labour MP for Acton, speaking in 1956, many people were "living in deplorable conditions and suffering all kinds of nuisances and inconveniences because of the irregular way in which our towns and cities have grown up".

In an era of planning and reconstruction there was a feeling that something ought to be done to bring order to the increasingly disordered capital.

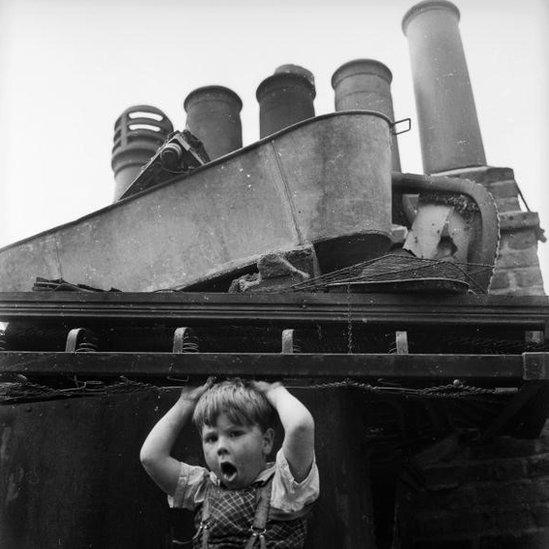

1961: A child plays among rubbish dumped on the roof of a building in the Wapping slums, east London

Harold Macmillan's government set up a commission in 1957 under Sir Edwin Herbert which recommended getting rid of the LCC and creating a new outfit altogether, the Greater London Council.

The commission recommended creating 52 local authorities as "the London boroughs" - a far wider official conception of the capital than ever before. Some areas fought desperately not to be included.

In the end 32 London boroughs were approved setting out for the first time the shape of London as it is defined today,

Each borough was represented by two members on the GLC, which shared responsibility with the boroughs for providing roads, housing and leisure services. The GLC was to provide direction through wide-ranging "development plans" for how to manage population growth and encourage prosperity across the city.

The 1960s and 70s

The Thamesmead Estate in Abbey Wood was one of the GLC's large housing projects

Before the GLC had even assembled for the first time, there were problems - not least of all bureaucratic. The Times reported that as some employees in the old LCC had been given new jobs in the GLC they found themselves in the position of having to write to themselves with requests for action.

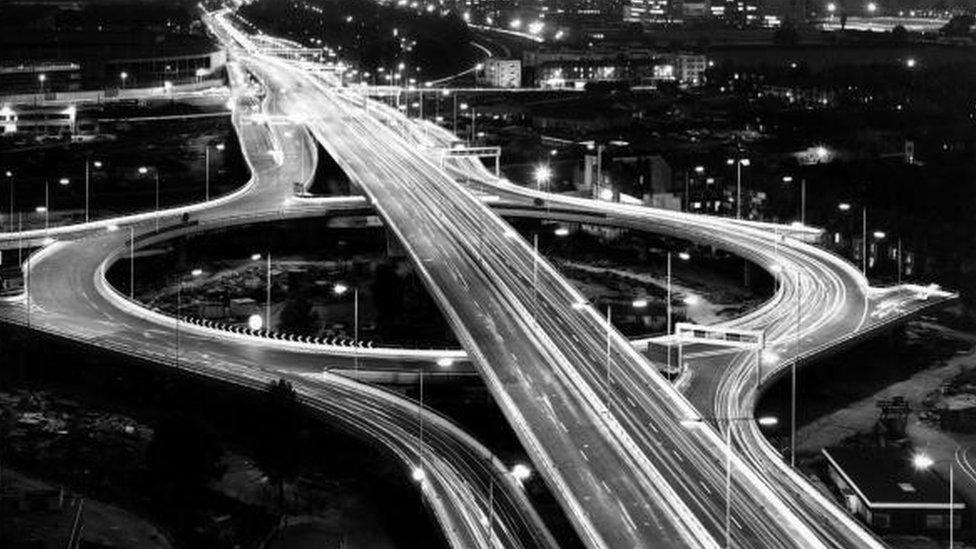

Its early practical endeavours ran into difficulty. A network of motorways known as the London ringways was meant to relieve congestion but faced fierce opposition - and although it began construction in 1969 the roads were never linked up as originally envisaged. It was finally cancelled in 1973. The elevated Westway linking Paddington to Kensington remains, a relic of the beleaguered project.

The GLC had no magic wand to wave over the capital's clogged roads. Even prime ministers were at their mercy. On one occasion in 1972, Ted Heath tried to travel 300m from the Commons to Downing Street and was so incensed at getting stuck in traffic that he phoned the GLC leader Sir Desmond Plummer demanding an explanation - but Sir Desmond happened to be in Tokyo at the time and was unable to help.

Its record on housing was similarly mixed. The GLC inherited slum clearance powers from the LCC, but when it began efforts to relocate Londoners from dilapidated inner-city homes to suburbs or satellite towns they were strenuously resisted by people living there.

The construction of the first of several proposed motorways around London was fiercely opposed

The Westway, pictured 1970

Barnstaple in Devon held a referendum in 1967 on "London overspill" and rejected the idea, fearing the "despoilment" of the countryside, according to The Times.

From the late 1960s, the GLC was at the centre of a fundamental shift in the philosophy of local government which was to mean its role as a housing provider was reduced.

When the Conservatives took control of the GLC in 1967, Horace Cutler was put in charge of the housing committee. He believed local authorities had no place as property owners and introduced a scheme to allow tenants to buy their homes at a discount, a scheme which influenced Margaret Thatcher and paved the way for the right-to-buy.

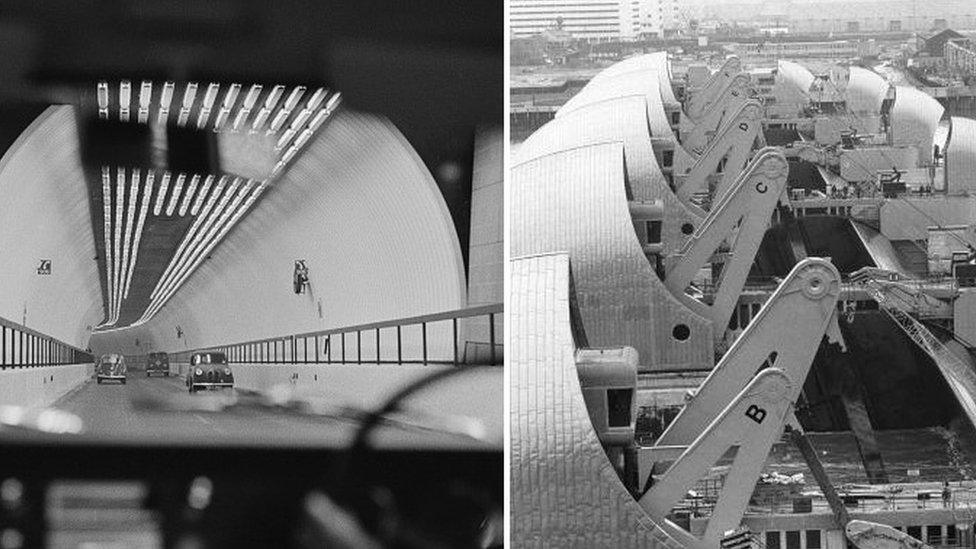

Despite the diminution of its original grand plans for housing and transport, the GLC did change London. It helped renew or build landmarks such as the new Blackwall Tunnel, the Woolwich Ferry and the Thames Barrier, as well as putting money into the arts and fighting air pollution.

The GLC worked on London landmarks including the Blackwall Tunnel and the Thames Barrier

The GLC was held back from more significant progress by two strands of political tension: one, between central and local government and two, between Conservative and Labour members on the GLC.

Control passed from Labour to Conservative and back again four times in the GLC's 21-year life span. To complicate matters, the leading party on the GLC was almost always the opposite complexion to the one in power at Westminster.

There were, in the words of Birkbeck's Prof Jerry White, "wild swings in political control and policy direction".

Projects were "blocked from above by government and below by the borough" - whether it was the outer boroughs' refusal to co-operate with efforts to rehouse Londoners there or the 1973 Labour government's temporary reversal of the project to promote council house sales as led by the GLC's Conservatives.

Livingstone at the top

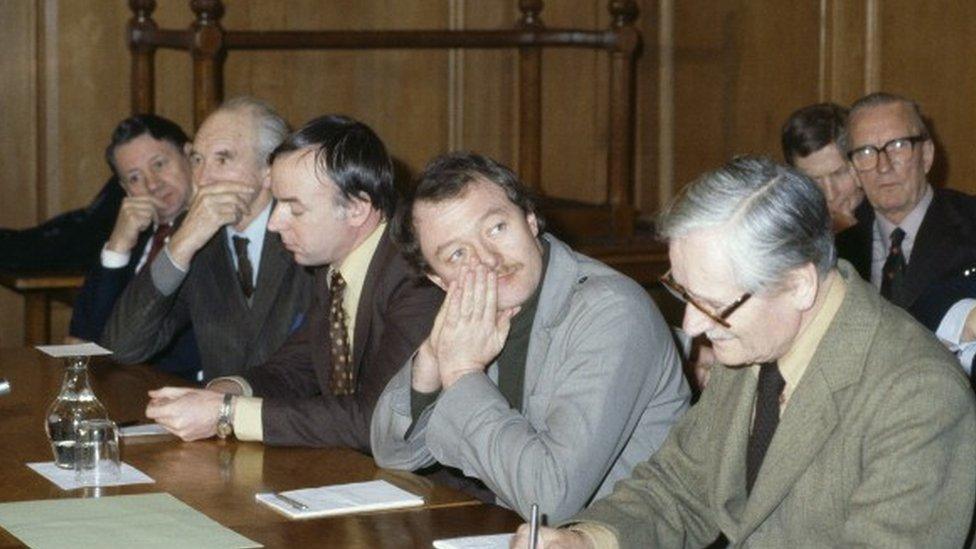

Ken Livingstone at a meeting of the GLC in 1981 shortly before he became leader

This pattern of political jockeying in the 1960s and 70s may have meant the ingredients for the GLC's downfall were already there. But it entered a completely new era in 1981 when a young councillor from Lambeth, Ken Livingstone, came to the fore.

He was 27 when he was first elected to the GLC in 1973. He recalls: "I remember thinking, I just want to spend the rest of my life here.

"My first job there was as vice-chair of the film viewing board so I was basically being paid to watch dodgy films all day."

From there he took up a housing role where he immediately kicked up a fuss about cuts in the GLC's house-building budget, and was sacked. He thinks this contributed to making him a public figure, saying his critics have always helped raise his profile.

"If Thatcher had just ignored us," he suggests, "no-one would have ever heard of us."

The manner in which Mr Livingstone came to lead the GLC is still notorious.

He had been beaten to the leadership of the Labour group on the GLC by the moderate Andrew McIntosh in 1980 - but was by that point openly leading a left-wing grouping of the party with the declared aim of "taking over the GLC".

The day after Labour won control of County Hall in May 1981, party members met and called a leadership election in which Mr Livingstone beat Mr McIntosh by 30 votes to 20 to become leader.

In Parliament the Conservative MP John Hunt condemned it as "a pre-arranged coup carefully concealed from the electorate".

Defending his actions now, Mr Livingstone says: "Andrew McIntosh just didn't understand how politics worked.

"He wasn't interested in talking to the whip, to his deputies. He wasn't interested in getting things done."

One of the first things he did on becoming leader was to introduce the "Fares Fair" policy, a 25% cut in London transport fares subsidised by higher rates.

Like many of his ideas, it inspired enthusiasm and abject horror in equal measure.

Particularly aggrieved at the rates rise were the Bromley Conservatives, who challenged it in the High Court and won.

Although his most famous policy was killed off in its infancy, Oxford University's Prof John Davis argues: "It was really his posture as leader of the GLC that made Ken Livingstone stand out, not projects or policy per se."

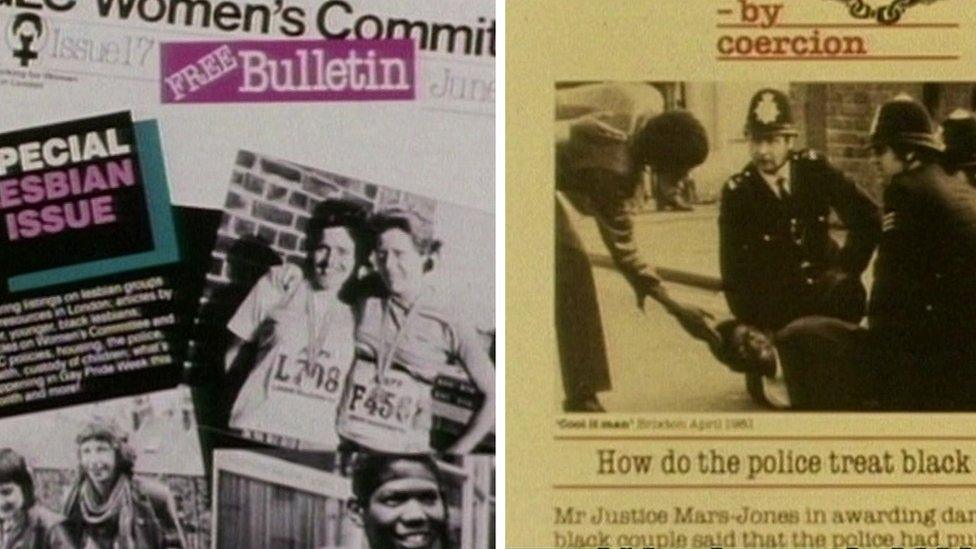

That posture was the active promotion of a new brand of left-wing politics with an emphasis on minority rights. It was sometimes known by its sympathisers as "the rainbow coalition", and mocked by its detractors as "the loony left".

Ken Livingstone and other GLC members - including John McDonnell - unveil a giant sign above County Hall showing the number of unemployed in London

It was embodied in the establishment of committees on the GLC representing women, ethnic minorities and gay people, as well as a committee which informally scrutinised the work of the Metropolitan Police.

These causes might seem relatively uncontroversial now, but at the time they were viewed as daft or even subversive by Livingstone's critics.

Prof Davis explains: "It wasn't just his campaigns - although gay rights and police oversight were certainly viewed more suspiciously then than they are now - but the way he went about it, sometimes handing out money to groups which hadn't been properly vetted."

Bob Neill, the Conservative MP for Bromley and Chislehurst, sat on the GLC in its final years and recalls: "It was an extremely fractious, highly politicised place to work. I didn't see anything like that again until Corbyn became leader of the Labour Party."

Mr Livingstone's answer to his critics is that "the job of a leader is to lead - we've all grown used to Blair era of focus groups, but your job as a political leader is to think about what you want your city or country to be 20 years down the line and then lead the debate."

He added: "Some of the things you do will be unpopular at the beginning, but by the end of five years there was support for every one of our policies, with the exception of LGBT rights."

Mr Livingstone's activities inevitably brought him into conflict with Margaret Thatcher, who had begun her decade at Number 10 just before his ascent to the top of the GLC.

As if his plan to raise rates had not been provocative enough, he adopted a number of stances which seemed designed to get under the skin of Conservatives: declaring London a "nuclear-free zone" in 1981, declining an invitation to the royal wedding, publicly supporting Irish republicanism and erecting a sign on top of County Hall proclaiming the number of unemployed in London.

He was nicknamed "Red Ken" in the press and Private Eye ran a cartoon series comparing him to Lenin. Margaret Thatcher was regularly briefed on what her policy unit called "the left-wing extremists" in London.

Mrs Thatcher herself was circumspect in her public remarks about Livingstone, but she told the Commons as early as 1981: "It is quite clear that some defence is needed against the reported activities of Mr Ken Livingstone."

But the GLC was merely the most conspicuous example of a wider theme across the country.

Conservative MPs were concerned about what they saw as "Marxist experiments" by Labour councils from Hackney to Liverpool, and Mrs Thatcher condemned them as "big spenders of other people's money".

Cambridge University's Prof David Runciman has written that "hard-left Labour councils" along with the IRA and NUM were "for Thatcher… all of a piece: each sought to supplant parliamentary government with direct action and threats of violence".

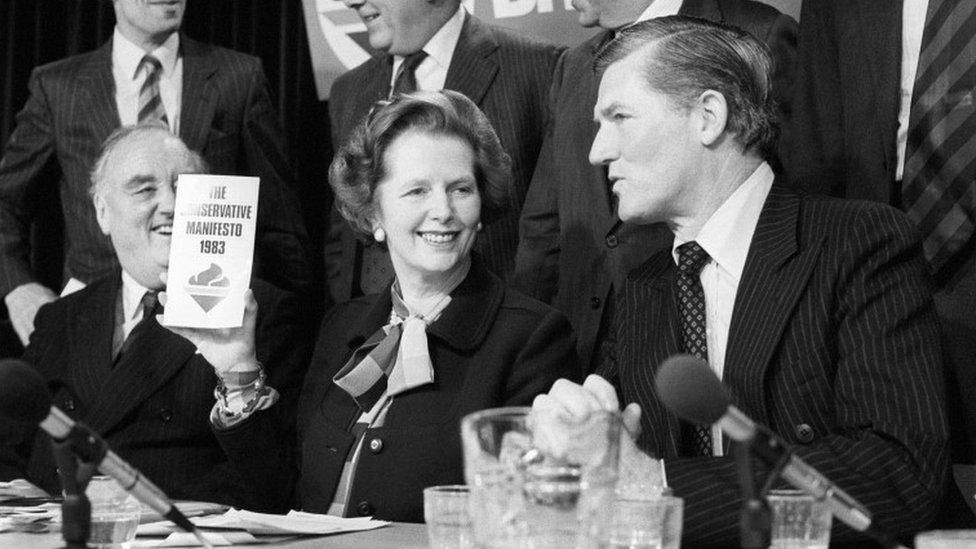

It was in this context that the 1983 Conservative manifesto promised to abolish the GLC, "a wasteful and unnecessary tier of government".

When Mrs Thatcher was re-elected and prepared to dismantle the GLC there were protests on both sides of the political divide. The House of Lords forced a delay. But in 1986 it met for the last time.

Failed experiment or future model?

But the locked chamber at County Hall is not all that remains of the GLC.

The most obvious legacy is the Greater London Authority, the system of an elected mayor and assembly created by Tony Blair's government after a referendum in 1997.

"One of the most crucial innovations of the GLA was the devolution of Met Police oversight to the mayor - and that can be traced back to the GLC's efforts to scrutinise the police informally," says Prof Davis.

It is a formula which the government is now trying to replicate elsewhere in the country, through police and crime commissioners, city region mayors and combined authorities.

The philosophy behind the GLC also seems to be enjoying something of a renaissance.

"The creation of the GLC was a real attempt to start from scratch on a blank page and say, our city is growing, how do we manage it? Something similar is being attempted now with the government's 'Northern Powerhouse' idea."

Prof Davis points out there are differences between the two ideas. The current government's commitment to big transport projects was not a hallmark of the GLC's work.

The current drive for devolution is an effort to deliver more power to existing local structures rather than designing a new body from scratch.

Perhaps most surprisingly of all, it is not just the ethos of the GLC which is making a comeback but its starring members.

When Boris Johnson was elected mayor of London, the BBC was not alone in commissioning "end of an era" political obituaries of Ken Livingstone. The consensus was his central role in London government dating back to the 1970s was over.

Ken Livingstone on winning the mayoralty in 1999, and Boris Johnson in 2008

But then Mr Corbyn was elected Labour leader and Mr Livingstone came to the fore again as part of the party's defence policy review. Shadow cabinet positions were also given to Diane Abbott and John McDonnell, an unlikely second coming for the political movement born in the London Labour Party of the 1980s.

Bob Neill laughs as he confesses to "a sense of déjà vu".

He adds: "But I am very worried, because it was a type of ideological municipal socialism which didn't really deliver efficient services. It's worrying that that hardline doctrinaire approach has returned."

Even Mr Livingstone admits he was surprised to see Mr Corbyn elected but maintains that in him voters see "someone who'll stand up for us".

Critics of the GLC experiment may have classed it as "Marxist", "mad" and "doomed" - but it's not quite over yet.

- Published7 March 2016

- Published25 December 2015

- Published10 April 2013

- Published21 May 2018