Covid: 'Young medics have seen more deaths than some do in a career'

- Published

Junior doctors Gita and Rita Deb - who are twins - say their mum is proud that both of them have kept going during the pandemic

Dozens of the nurses and doctors at Ealing Hospital in west London are at the start of their medical careers. About a third of the workforce is under the age of 30.

How have these young medics coped in a year of unprecedented strain on the NHS?

'I found myself in the middle of it'

Fathma Shabbir says she feels grateful to be able to give back to the community

On 14 May 1995, Fathma Shabbir was born at Ealing Hospital. Now she spends many hours every week running around a coronavirus ward helping to care for patients who are very ill with Covid.

"Ten intensive care beds doesn't sound like a lot," Fathma says. "But when we have a patient who dies or who moves on to another ward for recovery, that space gets filled with a fresh patient who needs to be cared for.

"During the peak in the first wave, we extended our ward to 16 patients and the turnover was still really fast.

"There were patients on a list waiting to come in. When one passed away or got better, another one could come in.

"I was a student nurse not long ago and then worked a year on intensive care, after which Covid started. I found myself in the middle of it.

"I work here three to four days a week and it's been really tough. Over the past 12 months I have seen so many people die. I had a shift where three people died."

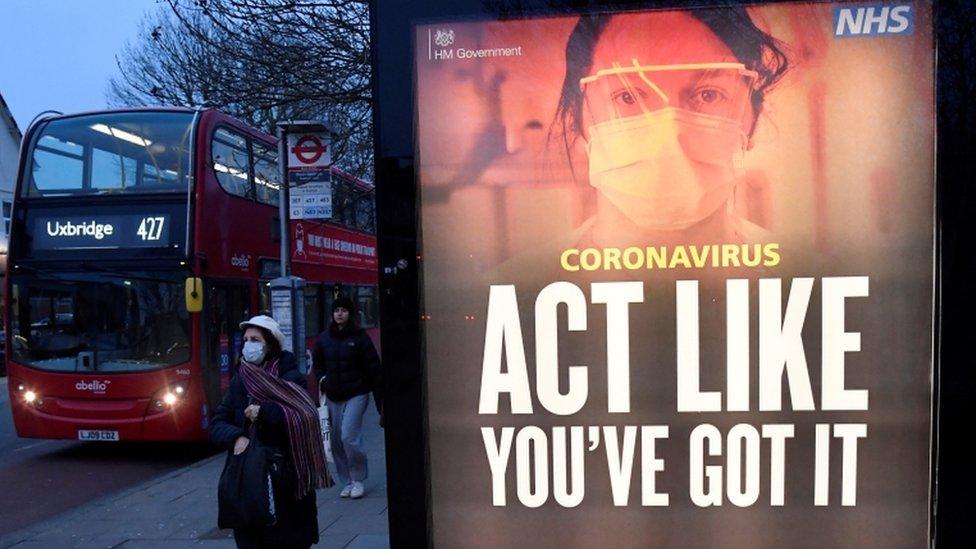

Ealing has been one of the worst affected boroughs in London during the coronavirus pandemic

"Sometimes it really gets to me," she says. "I look after patients who have multi-organ failure secondary to Covid-19; we support their lungs and many times their kidneys and heart.

"At the end of the shift I'm exhausted, but I know it's all worthwhile. I was born in this hospital so I feel grateful to be able to give back to the community I was raised in."

'I have seen staff crying in silence'

Dr Harmandeep Singh: "We are in a war against an unknown enemy"

Harmandeep Singh is the operational lead dealing with the Covid response at Ealing. He says the increased workload has left him and his colleagues exhausted and traumatised.

"PTSD is what a lot of war veterans suffer from," he says. "It is similar here, we are in a war against an unknown enemy which you can't fight off with guns but only fight off with science.

"For young nurses and doctors, who let's say have graduated last year, they come into the job and have seen so much sickness and people dying in front of their eyes. It can be psychologically traumatising. I have seen staff members cry in silence because they have seen so much death.

"The amount of sickness and death which our young staff have seen is probably a lot more than compared to a whole lifetime of some of the clinicians."

The 37-year-old consultant fears that what's happened over the past 12 months will have a significant effect on the mental health of young nurses and doctors.

"I can already see a lot of senior members of staff retiring early; a lot of members of staff discussing options to move out of their careers because of the impact it has had on their mental health.

"These younger members of staff have been the ones who have been holding hands with these patients on their way to recovery, so we should be proud of their hard work.

"But, at the same time, we should be careful about what they have been through, and what is coming up in the future, so they are supported through their careers so they don't desert us if we need them again."

'The patient was dead but still getting texts'

One of Dr George Hulston's responsibilities is to pronounce patients dead

George Hulston was always good at science at school and liked the idea of going into medicine. After five years at university, he became a junior doctor and has worked his way up to the position of registrar.

This time last year, the 29-year-old found himself dealing with the pandemic at one of the UK's hardest-hit hospitals, Northwick Park, which is part of the same NHS trust as Ealing.

"We had a lot of sick patients," he says. "The shift I most remember, and I will never forget, was a night shift on a Tuesday.

"I was going around the ward seeing patient after patient, seeing oxygen levels dropping, people requiring more and more oxygen and I was going to see people when they died."

One of George's responsibilities is to pronounce patients dead. He does this by listening to the heart and lungs for three minutes, checking for signs of life.

"It's not a nice thing to have to do and I did six in one night, which I couldn't fathom," he says.

"There was a man with a phone that had missed messages from family and I just thought: 'These are human beings, people who were very much alive a few hours ago and now they are not'.

"When we normally see people die, they slowly get worse with a chronic disease or they are frail and it is something that has been coming for months or sometimes years. But these were people who two hours before had been reading a book, receiving messages from their family and now they were dead. It was really horrible."

The doctor is pictured here with a patient who is about to have a continuous positive airway pressure therapy mask fitted

George finds it hard to switch off when he leaves work. Turning on the news or scrolling through social media serves as a reminder of the scenes he has just left in Ealing.

"It is very tough being on the front line," he says. "I want to carry on what I am doing but I think some people have changed their mind based on what has happened.

"That hasn't happened to me, I like my job, but it has had an impact on people's training.

"If you spent a year of your training as a doctor looking after Covid patients and not looking after your relevant speciality, you miss that period. So people are going to have to gain a lot of experience very quickly in the normal stuff and non-Covid stuff."

'My dead colleague's photo was still on the wall'

Dr Dervla Ireland says at one point there were as many as 10 deaths a night

Fresh from university, Dervla Ireland had just started out as a junior doctor last March.

The 25-year-old, who is now based at Ealing Hospital, was working at St Mary's Hospital in the early stages of the pandemic.

Patients were initially being transferred by people wearing hazmat suits, Dervla recalls.

"We had patients on the highest amount of oxygen you could deliver and they just weren't getting better," she says.

"Sadly, one of the nurses on the ward [Melujean Ballesteros] got Covid and died very quickly. The whole team was in shock. I was on a night shift going back to that ward and still seeing her photo on the wall and having to go verify another death. We were seeing several deaths a night, up to 10 a night.

"She was a similar age to my mum, who is a nurse, and that could have been her had she been working in London. They did a memorial and so many people wanted to go, but we couldn't at that point."

Dr Ireland's colleague Melujean Ballesteros worked and died at St Mary's Hospital in central London

Dervla has now endured two coronavirus waves, and worked at two different hospitals during the pandemic.

The young nurses and junior doctors at Ealing survive in the job by supporting one other, she says.

She sometimes does locum shifts to support the colleagues she knows would do the same for her.

"I hope the worst of it is over," she says. "If there was a third wave next winter I would have some time to recover, but if it was, say, in May I really don't know as it would be exhausting.

"Even once we are through this, I know I want to do general medicine and that will involve working as a registrar, and that is an intense job.

"I'm signing myself up to a life which has these pressures, but the passion is still there - it is hoping we have enough colleagues to run the service and look after ourselves."

Mental health support services are available to NHS staff, external, including a hotline that is operational seven days a week.

- Published2 June 2020

- Published15 January 2021

- Published22 January 2021

- Published9 February 2021