Museum of London Docklands: 'The past is problematic in this country'

- Published

The Museum of London Docklands, which was first called the Museum in Docklands, is based in a warehouse built in 1802

In 2003 a new museum opened in a Grade I-listed Georgian warehouse in London's docklands to explore the history of a part of the capital which at its height was the busiest port in the world.

"There were 700 acres of waterways here when they had the whole dock system and there were 50 acres of warehouses. It was massive - 35 miles of quayside, 1,000 ships a week coming in and coming out.

"It must have been incredible," says Douglas Gilmore, managing director of the Museum of London Docklands.

The surrounding area of Canary Wharf has changed radically since those days and has continued to do so over the two decades since the museum opened, with new skyscrapers popping up to dramatically alter the skyline.

The Port of London was once the busiest in the world with goods arriving from all over the globe

Yet Mr Gilmore says nothing about the museum's mission has altered.

"The area has changed dramatically but we still tell the story of trade, of migration, of this part of London and its development," he says.

Part of that story includes the exploitation of people. The museum has one of only three permanent galleries in the UK dedicated to the history of transatlantic slavery. It also looks at the lives of the dockworkers who worked in the port.

"There were 200 call-on points where the foreman would come out in the morning and just throw chips down and on the floor and you'd have to fight for them, and if you got one you could go and work that day.

"This was this is how we treated our workers," he explains.

The port was badly damaged in the Blitz and further declined from the mid 20th Century as ships became too large for it

In recent years, the museum has found visitors are increasingly keen to explore this sometimes troubled history.

"The past is problematic in this country," says the museum's senior curator Jean-Francois Manicom.

"It's our responsibility in the coming years, in the coming months, in the coming decades, to make the audience... understand that this is your story."

He points out that life in Britain today is still affected by the transatlantic slave trade, such as the railway line built in the 1800s between Birmingham and Liverpool that was partly funded by the compensation paid to slave owners when slavery was abolished. (Although the UK did outlaw slavery several decades before the US, albeit an achievement that's seen by some as being viewed today with "a slight whiff of self-congratulation".)

"All the physical landscape of UK is impacted by slavery," says Mr Manicom, who grew up in the French-Caribbean island of Guadeloupe.

Plans for a new museum began when the London Docklands Development Corporation was set up in the early 1980s

It is these stories about how the past affects us today the museum is planning to carry on telling as it looks towards the next 20 years.

New exhibitions are in the works - one in October will look at the impact of London's Jewish designers on the fashion world - while there are also plans to increase the numbers and diversity of audiences, such as by offering more family weekends featuring the popular Mudlarks gallery.

What goes on display inside the museum and how it is shown is also being considered carefully. Mr Gilmore says he pictures the building as being empty while he and his team work out how to develop the venue.

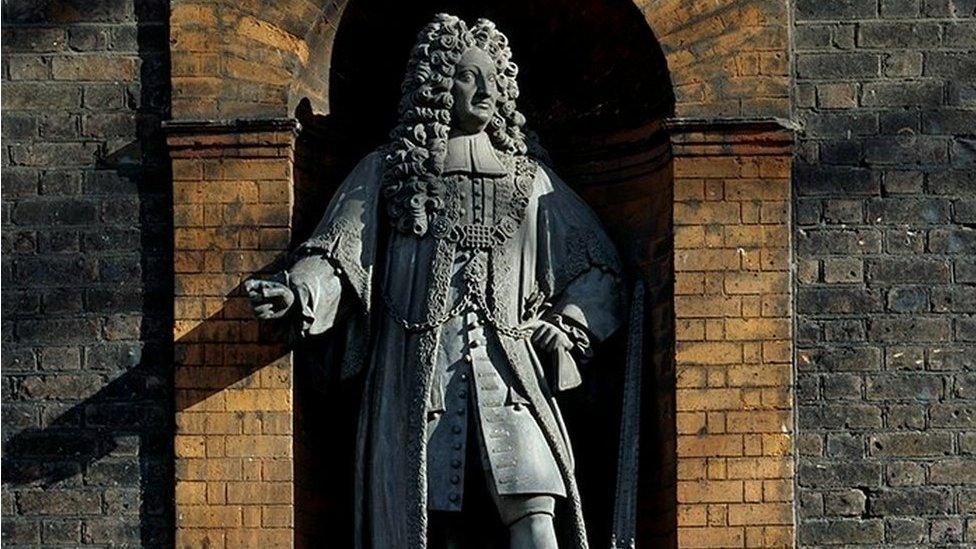

One item the museum is trying to work out what to do with is a large statue of slaveholder Robert Milligan.

The statue of Robert Milligan was removed by the Canal and River Trust to "recognise the wishes of the community"

Until 2020 the monument stood on a plinth outside the museum's front door but was removed by Tower Hamlets Council and the Canal and River Trust in the wake of a statue of slave trader Edward Colston being torn down in Bristol.

"They did a public consultation and that's what was decided, to have it removed, and then it just sat sort of in limbo for a while and there was a whole debate because no-one knew who owned it; it was really bizarre.

"That's when we decided to take it into the collection because it's part of the story of London," Mr Gilmore says.

While no decision has been taken about what to do with the statue, Mr Gilmore thinks having such an item "can create difficulties but I think you do embrace it" - even if this approach will require some creativity.

"The thing is, it's a huge object so it looked so big outside this great big building. But if you brought it into the gallery, it would dominate the gallery and I don't think that's what you want to do."

The museum was opened by Queen Elizabeth II in June 2003

Back outside on the docks, the museum is working with City Hall to create a very different memorial - this one to the victims of the transatlantic slave trade.

"We're giving information and knowledge, but people wanted more than that and they're waiting for more than that from us," Mr Manicom says.

"This memorial, it's supposed to be the missing part of what we're offering."

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published17 June 2022

- Published22 November 2022

- Published24 January 2023

- Published4 December 2022

- Published24 March 2023