Titanic disaster: How history has judged Bolton's sea captains

- Published

Sir Arthur Rostron (L) and Stanley Lord, captains of the Carpathia and Californian

Every great drama needs a hero and a villain. In the Titanic drama, the town of Bolton provided both.

According to the history books, Sir Arthur Rostron was the hero and Stanley Lord the villain. But how fair is that verdict?

On the night of the disaster, Rostron and Lord - both from Bolton - were in charge of two of the closest ships, the SS Carpathia and the RMS Californian.

As water poured into the stricken ship, the Titanic's crew fired off distress flares and hammered out SOS messages on the ship's wireless.

The Carpathia, more than 50 miles to the south-east, picked up the messages and raced to the rescue through the ice field.

All non-essential power on the ship was shut down as Rostron pushed his ship to the limits, ordering his crew to prepare hot food, blankets and medical care for the survivors.

Titanic author Lindsay Sutton said: "Rostron and his crew were magnificent. They couldn't have done more.

"There's a story that as the needle went into the red, the chief engineer [of the Carpathia] dropped his cap over the dial so no-one could see."

The Carpathia reached the scene three hours after the sinking. More than 700 people were rescued.

Bodies floating

Meanwhile, just 20 or so miles to the north was Captain Stanley Lord in the Californian.

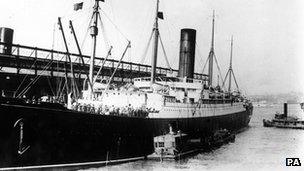

The Carpathia rescued more than 700 passengers

Lord, unlike Captain Smith on the Titanic, had halted his Boston-bound ship for the night because he was caught in the ice field.

Earlier, he had told his wireless operators to alert other ships in the area to the icebergs.

The Titanic's wireless operators told Californian's operator to "shut up" and they ignored the warning.

Later that night the Californian spotted the flares from the Titanic.

Lord was woken - twice - but said the flares were probably "company rockets" - signals between ships from the same line.

He took no action. His wireless office had shut down for the night and couldn't receive the Titanic's SOS messages.

It was only when the office re-opened that morning that the signals were picked up.

By the time the Californian reached the scene, the Titanic had sunk and there were just bodies floating in the water.

'Honour the Rescuer'

The Board of Trade inquiry into the disaster was critical of Lord's inaction on the night. He wasn't charged but his employers, the Leyland Line, dismissed him later that year.

The Carpathia reached the site of the sinking in three hours

Lord wasn't allowed to present his case at either the British or American inquiries. In the aftermath, he became, in the public's eyes, the villain of the hour.

Meanwhile, Rostron was feted on both sides of the Atlantic.

He was given a Congressional Medal of Honour and was knighted by George V. He rose to become Commodore of the White Star Line.

He was an old boy of Bolton School where they still celebrate his heroism.

A picture of an elderly Rostron talking to a group of entranced schoolboys in the 1930s is included in small commemorative exhibition at the school.

Former pupil Ann Willams is campaigning for a permanent memorial and has set up a website called 'Honour the Rescuer'.

"Arthur Rostron was celebrated at the time but I would love to see a proper memorial to him," she said.

"Perhaps a lifeboat could be named after him because the Carpathia was, I suppose, the greatest lifeboat ever."

'Harshly treated'

There's no doubt Rostron deserves the praise. But does Lord deserve the blame?

In the 1958 film A Night to Remember, Lord was once again portrayed as the villain. Lord demanded a new inquiry to clear his name.

After his death in 1962, his cause was taken up by the then Bolton East MP Bow Howarth.

"I thought it was worth looking at the evidence again because I just cannot believe that a man of his experience in that environment would have just ignored anything that could have been interpreted as a call for help. It doesn't ring true," he said.

The evidence was reviewed in the 1990s but once again Lord was criticised: Why didn't he react to the flares? Why didn't he wake his wireless officers and get them to investigate?

They suggested that if Lord had reacted, another 200 could have been saved.

However, Mr Sutton believes that Lord was harshly treated.

"The Board of Trade inquiry needed scapegoats because they didn't want all the blame rebounding on them," he said.

"Their own regulations on numbers of lifeboats, on 24-hour wireless cover, on ice patrols in the North Atlantic were found wanting," he said.

"Lord isn't blameless by any means but circumstances conspired against him."

- Published11 April 2012

- Published10 April 2012