From crew to crockery: Liverpool's links to the Titanic

- Published

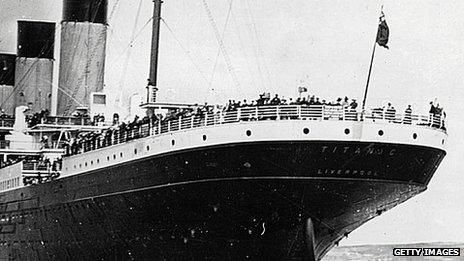

The name of the city of Liverpool was written on the stern of the Titanic

Liverpool's spectacular waterfront is dominated by monuments to the city's golden age of maritime and commercial power.

But one of the greatest monuments to that power is not here - it is lying a couple of thousand feet down at the bottom of the Atlantic.

The Titanic may have had Liverpool painted on its stern but the ship never visited the city. Even so, Liverpool can lay claim to be the doomed ship's spiritual home.

Titanic was born and took shape in Albion House, the headquarters of the Liverpool-based White Star Line. The building, with its alternating rows of red and white bricks, still stands at the corner of James Street and The Strand.

White Star was engaged in a fight with rival Cunard over the hugely lucrative Atlantic passenger trade. It was a battle where size - and luxury - did matter.

Cunard had nosed ahead by building the Mauretania and the Lusitania.

"White Star's president J Bruce Ismay had to hit back, so he came up with this plan to build three new ships bigger and better than Cunard's - the Olympic, the Britannic and the Titanic," said David Hill, from the British Titanic Society.

Substantial contribution

The Titanic was designed in Liverpool but the city never enjoyed the sight of it steaming up the Mersey.

"There was a plan for Titanic to visit Liverpool before she sailed down to Southampton for the maiden voyage," said Mr Hill.

"But the sea trials were delayed by bad weather and there was a rush to get her into service so she went straight down to Southampton."

Titanic might never have visited the city but Liverpool's contribution to the ship was substantial.

About 90 members of the crew came from the city, including the two lookouts who spotted the iceberg.

In fact, there were so many Scousers on board, the main crew passageway on the ship was nicknamed Scotland Road after the famous North Liverpool thoroughfare.

The Stoniers company, still prospering today, supplied 50,000 pieces of glass and crockery to the ship and and the engine room telegraph was built by J W Ray of Liverpool.

The musicians, who played on as the ship sank, were booked by Blacks, a Liverpool agency.

The company was publicly criticised after the sinking when it demanded payment for "loss of uniforms" from the families of the dead men.

One of the victims was a Liverpool man, Fred Clarke, who lived on Tunstall Street, just off Smithdown Road. The musicians are commemorated on a plaque in the city's Philharmonic Hall.

No Titanic mention

News of the ship's sinking and massive loss of life filtered through slowly. Mr Hill has a facsimile of a letter sent from the Liverpool offices to the Board of Trade claiming all passengers were safe.

A Titanic monument became the Engineers' Memorial

"It was a mix up of telegrams but sadly the good news didn't last long," he said,

"Less than 24 hours later, they sent a second letter reporting the loss of the ship and the rescue of six hundred survivors."

An appeal was launched to build a memorial to the Titanic's engine room crew, which now stands down by the landing stage on the waterfront.

It is an impressive sculpture, an obelisk surrounded on four sides by the figures of stokers and engineers.

Oddly though, it is a Titanic memorial without any mention of Titanic on it.

"By the time the monument was unveiled, it was 1916 and there had been huge loss of life in the world war and ships like the Lusitania and the Empress of Ireland had been sunk," said Mr Hill.

"It was felt that to commemorate just the Titanic engineers would be a bit insensitive so the memorial is to all engine room crews who'd died."

- Published10 April 2012

- Published10 April 2012

- Published29 March 2012