Breaking the cycle of poor literacy standards - one step at a time

- Published

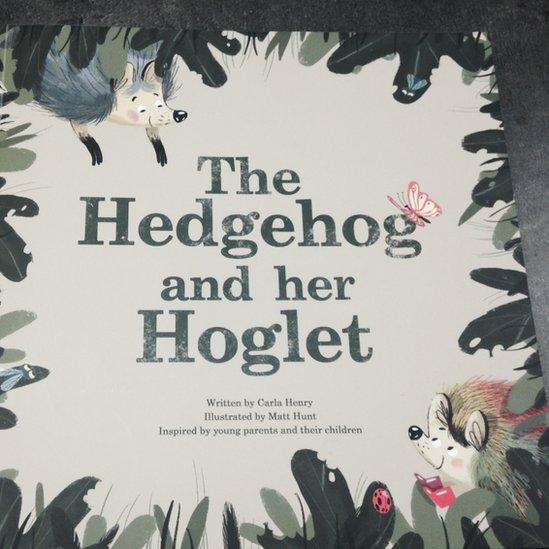

Hedgehog and her Hoglet was produced by a team of parents in Salford

Each year across Greater Manchester, two out of every five children are defined as being "not school ready" when they're assessed at the end of their Reception year.

While some of those 16,000 youngsters may eventually catch up with their peers, independent research, external carried out for the government suggests the majority will struggle to do so.

Literacy problems often go down through the generations, prompting education ministers and educationalists to pose the question: "What can be done to break the cycle?"

In order to encourage families to spend more time reading together, one scheme has seen a group of young parents from Greater Manchester producing their own children's book.

The Hedgehog and her Hoglet is based on the experiences of new mothers and fathers in Pendleton and Little Hulton in Salford.

Many struggle to read themselves and own few, if any, books.

David Stanley is a 24-year-old father of four from Charlestown.

"I'm not a strong reader and I'm not a person who'd read a book," he said. "But we do get a lot of books for the kids and we try our best to teach them to read."

Lynsey O'Sullivan, from the Lowry Arts Centre, hopes to break the intergenerational cycle of poor literacy

The project, funded by the Lowry Arts Centre and Salford council, aims to raise literacy standards.

"A lot of young parents told us they didn't necessarily have books in the house because they get ripped and they're expensive," said the arts centre's Lynsey O'Sullivan. "Now they're able to walk into a shop and see their book on the shelves."

Parts of Salford have been identified as having severe levels of deprivation, with poor educational attainment contributing to wider underachievement and poverty.

In Manchester, 36% of children assessed at the Early Years Foundation Stage had only "emerging" levels of reading in 2014, while 39% reached the same standard in writing by the end of their Reception year.

Those children were at a greater risk of being left behind throughout their school lives, said Dame Clare Tickell in her 2011 report, The Early Years: Foundations for life, health and learning.

Such problems often lead to low levels of economic activity, increased public spending and an intergenerational cycle of poverty.

Salford's experience is not a local one, though. The problem is nationwide.

In some pockets of the United Kingdom, up to 40% of the adult population lack the literacy skills expected of an average 11-year-old.

And, if nothing is done to tackle the literacy gap, the annual financial cost to the UK could be £2.5bn, according to accountancy firm KPMG.

Nick Gibb, Education Minister for England, said: "Tackling literacy failure is a priority for the government, and our plan for education is designed to ensure every single child leaves school prepared for life in modern Britain."

The Conservative MP's opposite number for Labour, Kevin Brennan, said: "It is vitally important that every child should leave secondary school with the literacy skills they need.

"It is up to the government, charities, schools, parents and communities to ensure that all children receive the best possible start in life."

According to government figures, 130,000 children every year in the UK leave primary school without being able to read well.

The National Literacy Trust says low literacy levels and poverty often go hand in hand.

Once established, both can be hard to crack.

If your parents leave school without any qualifications, you are more likely to follow in their footsteps.

Dame Julia Cleverdon, who chairs of the Read On, Get on campaign, said: "Two in five disadvantaged children are leaving primary school without vital literacy skills.

"This is the unacceptable consequence of child poverty in the UK, which is exacting both a life sentence on these children and a terrible toll on our society."

The early years of a child's life are vital when it comes to tackling illiteracy. According to specialists, the crucial period for child development is between late pregnancy and the age of three, by which time a child's brain is 80% functioning.

The Millennium Cohort Study looked at some 19,000 children born in the year 2000.

Researchers found that, by the age of five, children from low-income households were typically more than a year behind those from high-income backgrounds when it came to vocabulary.

Other studies have also demonstrated that the literacy gap emerges before children start school.

David Stanley says he tries to read with his four children as much as possible

One found that, by the age of three, children from the most prosperous households have heard 30 million more words than children from impoverished households.

Access to technology is thought to be another reason why poorer children are sometimes left behind - the internet now plays a huge part in children's learning.

A recent Ofcom survey of parents suggests 28% of three-to-four-year-olds now use a tablet computer at home.

While that may be great for those children, what about the families who simply do not have the money to buy such devices?

According to a report last year, children who are read to every day by their parents will be almost 12 months ahead of their age group by the time they start school.

Even reading to them two or three times a week gives them a six-month head start.

There's also a strong link between parents' interest in their child's education and the likelihood that their children will escape poverty.

Those who are poor at the age of 30 are significantly less likely to have been read to by their parents when they were children.

Viv Bird, chief executive of the Booktrust charity, which has been promoting reading for 90 years, said: "Reading together strengthens family bonds and helps children do better at school, whatever the family background."

Now, in some of the poorest parts of Salford, parents are taking pride in reading their own book to their own children.

Can such a small but practical step help break the cycle?

David Stanley certainly hopes so.

"I don't want them to struggle when they're older," he said. "So I try and spend as much time as I can with them, reading a book."