Victorino Chua: My meeting with Stepping Hill poisoner

- Published

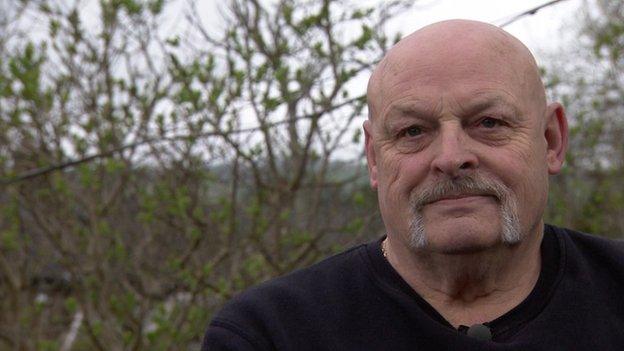

Chua invited BBC News into his home in Stockport six months after being arrested and spoke of his "anger, injustice and struggle"

Months before his conviction for murdering two patients and poisoning others, Victorino Chua unexpectedly invited the BBC's North of England correspondent Ed Thomas into his home. But what did the nurse, who it later emerged had written of a "devil inside" him, reveal during their encounter?

"I want to wear a placard around my body and walk to Stepping Hill. I want it to read: 'I'm Victorino Chua, accused of poisoning patients.'"

It was the first of many protestations of innocence from Chua, six months after his arrest for murder.

I could hardly move inside his terraced house in Stockport. All his belongings were in boxes. He told me he was selling up and moving to the Midlands to be with his wife and children.

His deep frustration was obvious.

"My doctor has told me to go to the gym to get rid of my anger," he said.

The technique was working, he told me, as he sat with his gym bag on his lap, arms crossed.

Chua's home was dark, every curtain drawn. He told me he was deeply religious. Pictures of Jesus and the Virgin Mary stared down from every wall.

He had become paranoid. The press and police all had an "agenda", he said.

I'd been sitting in his living room for half an hour when I finally asked the Filipino nurse for the first time if he had poisoned his patients at Stepping Hill Hospital.

He was calm and composed, staring directly at me as he considered his answer.

"I didn't hurt anyone," he said. "I only came into contact with two of the 21 patients, I would never harm anyone."

Did you tamper with medical records?

His answer was barely coherent, difficult to follow, but the quote I remember was: "I don't know who these patients were, I had nothing to do with it."

'Broke down and cried'

Chua said he enjoyed his work at Stepping Hill - his first job was working night shifts. He revealed he had a problem with one of his managers at the hospital but said patients "loved him".

"One woman, said 'Vic, I want to marry you'," he told me.

I then asked whether, if he was innocent, he was worried the poisoner was still inside Stepping Hill?

It was the moment Chua broke down and cried, the first sign of emotion. But he never answered the question directly.

"This is putting too much pressure on my family. I miss my children, my wife," he said.

"Bail conditions mean I'm only allowed to visit them once a week. My children miss me, they paint me pictures, they want to come back to Manchester."

The separation, he said, had caused him great pain, plus the added worry of his children hearing about the crimes their father was accused of.

After two years on bail, he began helping out at a local pet shop to pass the time and keep him calm, he said.

"What else could I do?" he asked. "I've been caring for people for 20 years."

Chua was first arrested in January 2012 and released on bail which was extended a number of times

Looking back, only one aspect of my first meeting with Victorino Chua stands out now as it did then.

As I sat there listening to him talk of anger, injustice and his struggle against thoughts of suicide I thought to myself: "He's not mentioned his patients, he's not said he didn't do it."

When I finally asked the question, the answer began with the story about the placard and his visit to Stepping Hill with a message of innocence.

After his conviction, Chua will never get the opportunity to parade himself in front of his former colleagues and staff, to seek their attention and play the role of a victim.

- Published18 May 2015

- Published18 May 2015

- Published18 May 2015