Holocaust Memorial Day: On the run from the Nazis

- Published

Judy said she was "very proud" of her mother's story of survival

Judy Wertheimer has had to live with the legacy of the Holocaust all her life, even though she was born long after it happened. On Holocaust Memorial Day, she tells the story of her mother Helen Taichner, a Polish Jew, who spent years alone and in hiding from the Nazis.

As a child, most of Judy's friends went to the seaside for their holidays. But for her, as the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, summer breaks involved trips to find out what happened to her relatives in the Nazi war camps.

Her mother, Helen Taichner, spent years evading capture by the Nazis in Poland - hiding anywhere she could find including in a toilet and coal cellar.

She told the BBC: "Nowadays children are taken to Disney in Paris as a trip to entertain them, but I was taken to Terezin to look for a family that may have died."

Judy's childhood was punctuated by the "burden" of hearing stories about the Holocaust and the relatives she had lost.

Her mother spent the first part of the war with her first husband and their young child, fleeing from town to town. Malnourished, she was unable to feed her baby, who died in around 1939 when Helen was 25.

In 1943, the couple decided to separate to maximise their chances of survival. It is not clear what happened to him after that but they never saw each other again. He died during the war.

Helen Taichner, born as Rachel Rosenberg, died in 1993

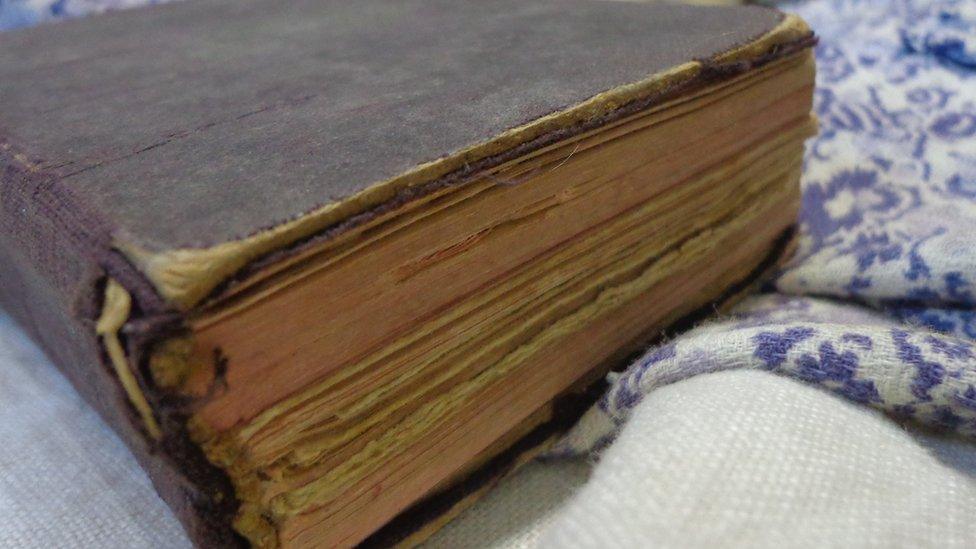

Later that year, when she was 29, Helen stayed with a family who gave her a missal and taught her how to behave in a church and how to pray.

"She was pretending to be a Catholic," Judy said. "If anybody stopped her, she knew the blessings, she knew the prayers."

Helen slept under trees and in churchyards until she met a maid who offered to shelter her in the house where she worked - a building divided into apartments.

The maid allowed Helen to sleep in one of the toilets without her employer's permission.

Judy said: "Anybody who looked after a Jew was putting themselves in a very great danger. These people were putting their lives on the line to save my mother. If they had been caught, they would have been killed."

But that was not the end of the struggles for Helen. She hid for five months in a coal cellar, where she survived mainly on bread and water.

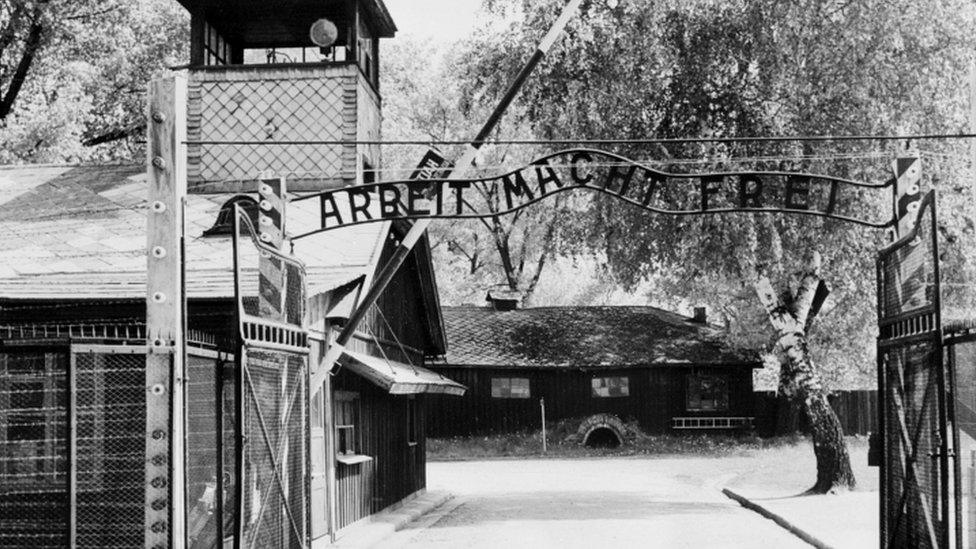

Life in Warsaw during World War Two

Soon after the war ended, Helen moved to Manchester to live with relatives, she had holidayed in the city before the war and wanted to start a new life.

She remarried and a few years later gave birth to her daughter.

Judy, who lives in Cheadle Hulme, Greater Manchester, said the Holocaust has cast a long shadow over her life but she is determined the same should not happen to her family.

"I can't pass it on to my children," she said of the family history. "It wouldn't be fair. They have to know but they mustn't feel the burden."

Helen died in 1993 and Judy has now decided to donate some of her mother's possessions to the Manchester Jewish Museum, where they will be permanently stored and passed on to future generations.

It is a part of the museum's appeal which aims to "find those treasures" that could tell the stories of Jewish people in Manchester.

Judy said she wanted to raise more awareness about the Holocaust by donating some of the possessions her mother had during her life on the run from the Nazis

Alex Cropper, curator at the Manchester Jewish Museum, said: "The appeal is really about going out to the community and finding out if there is anything in people's attics and backrooms that could be in our galleries in the future."

She added Helen's story was "really special" and the museum would be privileged to store some of her belongings.

"The items are incredible. Helen's story is not the survival story many people think about. She is not in a camp. She is not in a ghetto.

"She is by herself and she really relies on other people to help her hide throughout the war. It is an incredible story."

The donated items include a sock Helen wore while in hiding, a dress she wore on trips out of the cellar, a missal she used to disguise herself as a Christian and wooden shoe stretches hollowed out to hide gold.

The dress was made by the non-Jewish maid who hid Helen in a toilet and coal cellar

Judy is concerned people do not know enough about the Holocaust and there are many "non-believers who say it never happened".

"One of the main reasons to give my mother's things to the museum is so that it can be there as a permanent record and people can go in and actually see it," she said.

"The bottom line is this should not happen again. Nobody should rise up and try to take over people and just kill them for the sake of their religion."

Helen carried the missal every day she was in hiding

- Published24 January 2016

- Published7 May 2015

- Published22 October 2015