Greater Manchester Police officers allege force failing crime victims

- Published

Greater Manchester Police was placed in special measures in December 2020

"I wouldn't feel confident reporting a crime to my own police force."

These are the words of a serving Greater Manchester Police (GMP) officer who has chosen to speak to BBC Newsnight to allege serious failings within England's second largest force.

A number of officers, past and present, have also come forward to voice similar concerns.

In December, Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) found GMP failed to record about 80,000 crimes in a 12-month period and closed cases without proper investigation.

Former chief constable Ian Hopkins resigned after the force was placed in special measures, and successor Stephen Watson told a recent press conference vital improvements would be made rapidly.

"That is not to say GMP is a failing force," he said. "It is a force comprised of many thousands [of] genuinely hard-working, committed, brave, talented, professional people."

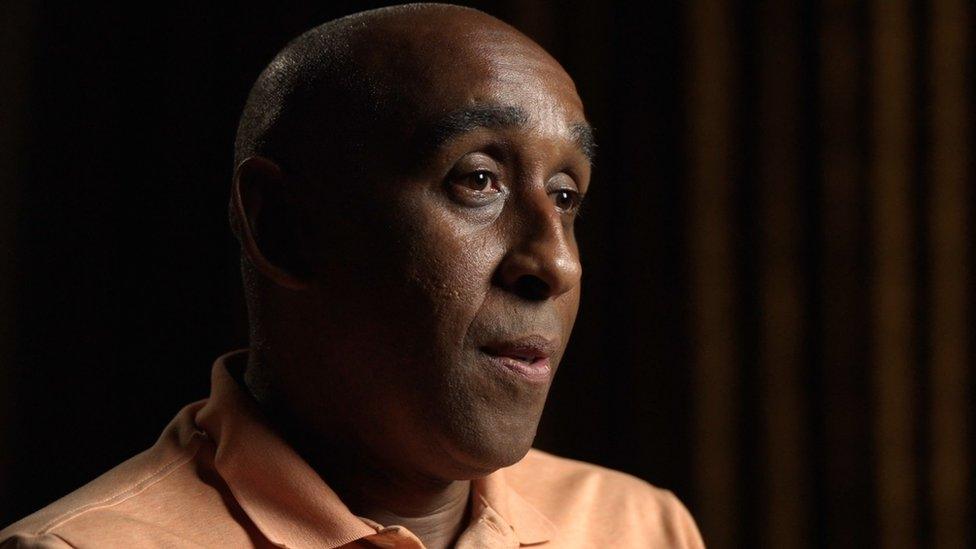

Scott Winters claims GMP puts its reputation ahead of tackling problems

Former GMP officer Scott Winters said he could not wait to leave the force in 2017 after 28 years of service.

In 2015, he took the force to an employment tribunal, later reaching an out-of-court settlement.

He claimed the force he loved working for had become one that put its reputation ahead of tackling problems.

Mr Winters described the police watchdog's findings as "dire", "unforgivable" and "abysmal".

And it is the public who suffer as a result, he said, with victims being let down.

"They are a victim of crime and they've not either had the crime recorded [or] a chance of the perpetrators being brought to justice and punished," Mr Winters said.

Some serving police officers say the situation within GMP has not improved, either.

One, who asked to remain anonymous, told Newsnight that criminals "are luckier now" as they are "literally walking the streets [and] not being arrested".

Chief Constable Ian Hopkins resigned days after a highly critical report into GMP

Almost two years ago, Patricia (not her real name) walked into Rochdale police station with her daughter who had finally found the courage to report allegations that a man had groomed and raped her.

Her daughter had been so desperate that she had twice tried to take her own life.

"We went in and the detective we spoke to already had a pile of papers on his desk and a photograph," said Patricia.

"He asked us 'is this the man in question?' and we said 'yes' and he said 'yeah, we know a lot of stuff about this man'.

"So I just thought: 'Brilliant, they already know who he is so it will be dealt with really, really well'.

"My daughter gave a really lucid account, and at one point I had to leave the room because I couldn't hear what had happened, what he had done. I just couldn't bear it."

'Absolutely incompetent'

But her daughter would then have to go on to retell the distressing account again. Since making the report, four different officers have been in charge of the case.

The phone her daughter handed in as evidence also temporarily went missing.

"To me they are absolutely incompetent, there's no other word to sum them up," Patricia said.

"What this man did has ruined probably the best years of her life," said Patricia.

"It's given her such bad anxiety that she's on antidepressants. Maximum dose. She can't sleep. She's just not the girl she used to be.

"He's caused all that and he's still out there. He's not even been arrested."

Stephen Watson (centre) was sworn in at a ceremony attended by Beverley Hughes, Deputy Mayor for Policing and Mayor of Greater Manchester Andy Burnham

The family are being supported by the Maggie Oliver Foundation for victims of sexual violence after not receiving the response they expected from the police.

Many have pointed to GMP's new computer system, which went live two years ago, as the catalyst of some of the failings.

Called the Integrated Operational Policing System (iOPS), it has been dubbed iFLOPS by many insiders.

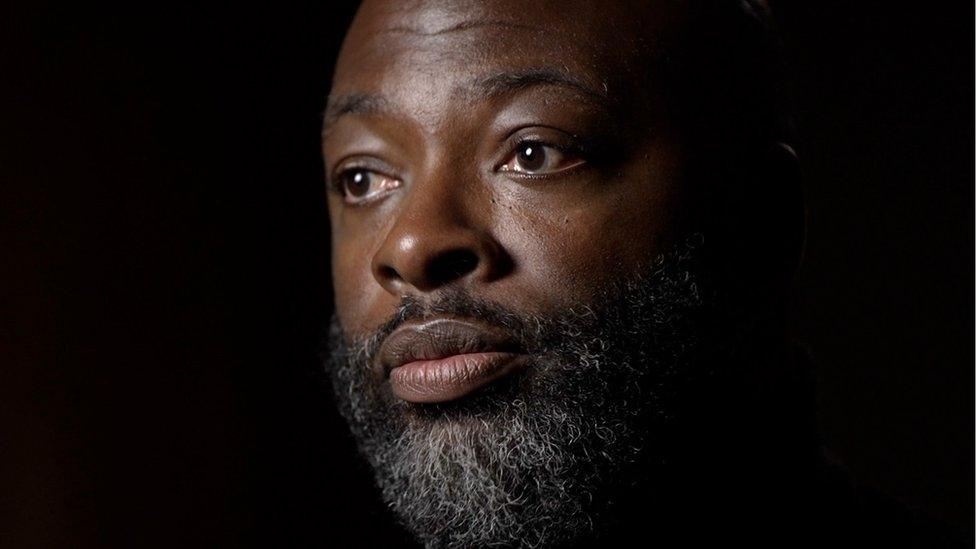

Until last year, Paul Bailey was a GMP detective working on major incidents. He remembers the frustrations of using iOPS.

"It felt like it had been designed by someone who had never been a police officer and never worked on the streets," he said.

"A simple example is if there was intelligence regarding firearms at an address or premises and officers were sent to that address and didn't know that, then maybe the outcome could be a poor one for everyone involved."

Paul Bailey has since retired from the force

The radio panic buttons linked to the system have also been a cause for concern, as Mr Bailey discovered when a colleague pressed it by accident during a shift.

The system should have located their car but it failed, he said.

"We could have been dying in a ditch and no-one would have known about it," he said.

With mounting concerns about public protection, the HMICFRS reviewed iOPS and published its findings in March 2020.

A catalogue of serious issues was identified.

But, 15 months on, some serving police officers say the system is still not fit for purpose.

"You could be dealing with gangster number one in Salford - major organised crime gang players - and there's a black hole where the recent intelligence should be," one told the BBC.

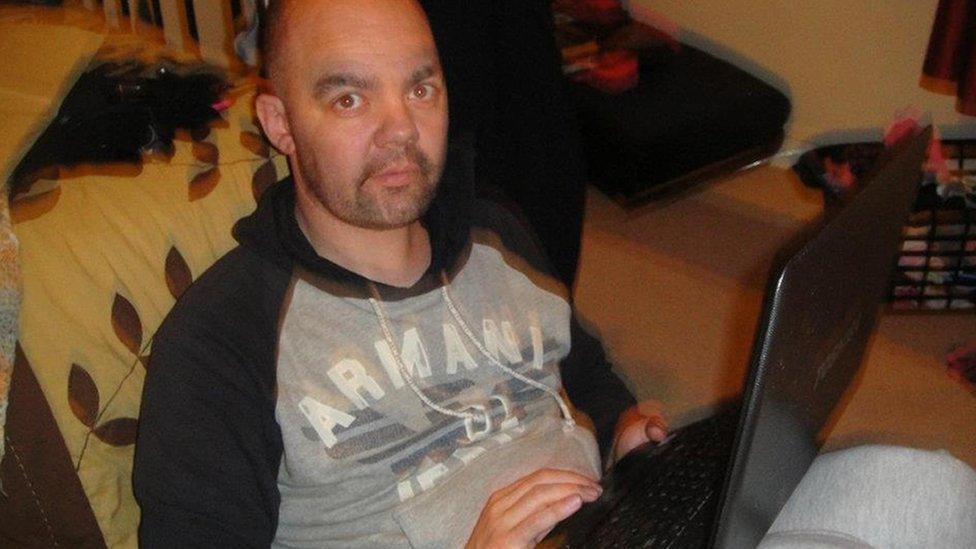

Anthony Grainger, 36, was shot dead in 2012 by a firearms officer

Gail Hadfield Grainger, whose partner Anthony Grainger was killed in a botched GMP firearms operation, said "it just seems like one failure after another".

Mr Grainger, from Bolton, was shot through the windscreen of a stolen Audi in a car park in Warrington in 2012. He was unarmed at the time.

A public inquiry found a "catastrophic series of failings and errors" including inaccurate information given to firearms officers.

"Anthony lost his life. The intelligence system was flawed [and] GMP were ordered by the judge to ensure that this doesn't happen again," Ms Hadfield Grainger said.

"I think these are serious, systemic changes that need to be changed from the root of the problem. I don't think this is a quick fix."

In a statement, Chief Constable Watson acknowledged that part of the iOPS system had "presented significant challenges" to GMP but it was under review and upgrades and improvements had been made.

He said the force "remains absolutely committed to protecting children, young people and all vulnerable people in our community.

"Some of the historic investigations, by their very nature are distressing, time-consuming and present multiple and complex difficulties for all involved and affected by the case.

"We are nonetheless determined to conclude our investigations thoroughly and to the evidential standards required to bring offenders to justice," he said.

You can hear more on Gail Hadfield Grainger's story in the documentary One Night in March on BBC Sounds and watch the Newsnight episode on iPlayer.

Related topics

- Published26 March 2021

- Published18 December 2020

- Published10 December 2020

- Published4 March 2020

- Published3 March 2020

- Published5 February 2020