Stillbirth: 'Finding my baby’s grave gave me comfort'

- Published

Lilian Thorpe shares her heartache after years of not knowing what happened to her baby

In 1961, Lilian Thorpe gave birth to a stillborn baby boy, but she never had the chance to hold him in her arms or kiss him goodbye before his body was taken away.

For six decades, she did not know what happened to his body or where he had been laid to rest.

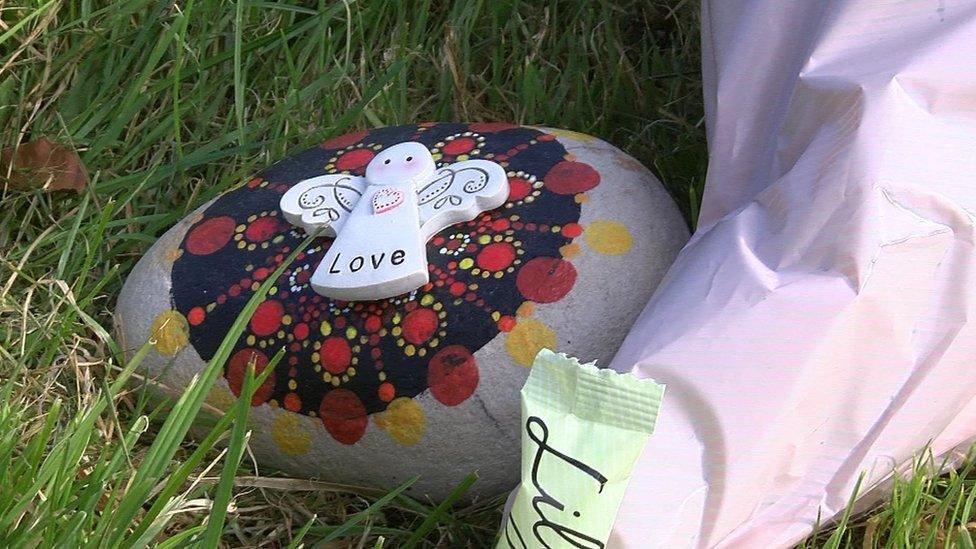

Standing in front of his grave, marked only by a number, she touches the ground.

"Your mummy's here," says the 86-year-old.

"Now I know where he is," she says, adding: "I just wish I'd have seen him."

Lilian, who lives in Stalybridge in Greater Manchester, believed her little boy's body had been "thrown away" after he was taken from her.

When he was born, it was the hospital which dealt with the arrangements after a stillbirth.

This meant Lilian, and many others who faced the same heartache, were never told what had happened to their children or where they were buried.

Lilian's son was buried on 1 December 1961 at Hyde Cemetery in Greater Manchester

Unbeknownst to her, she had spent many years living just two miles away from where her son was buried, in Hyde Cemetery, on 1 December 1961.

"I never thought this day would come," she says.

Lilian adds the sadness she felt after her son's death was "always inside", but was kept hidden.

"Even my friends didn't know what had happened."

She says she was treated "as if it was a nothing".

"To me, it was everything."

If you or someone you know has been affected by issues in this article, you can find support from BBC Action Line

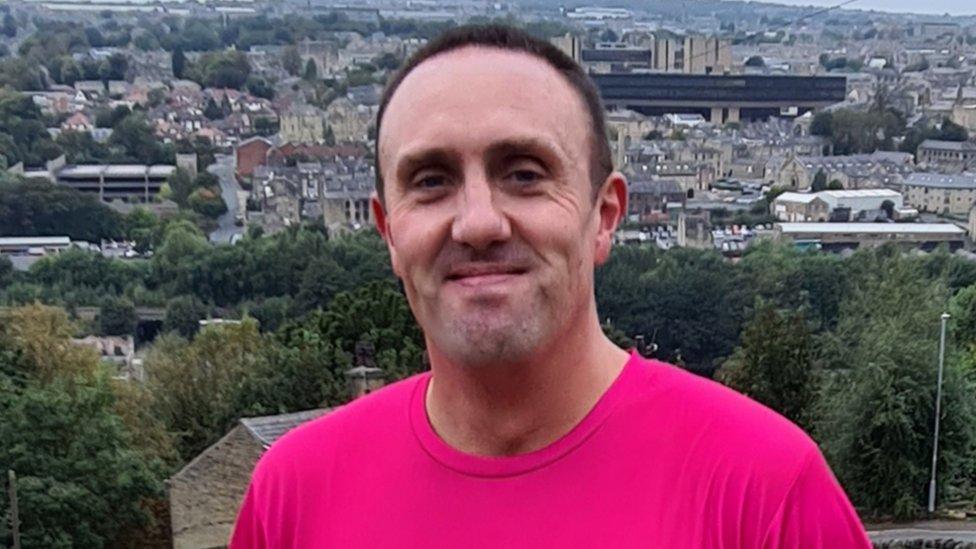

Lilian was finally able to visit her son's grave after BBC North West Tonight enlisted the help of Mike Gurney, head of bereavement services at Tameside Council, to find the answers she has always been desperate to know.

He searched grave records to find the baby, eventually discovering the details in the burial register for Hyde Cemetery.

He found there were eight other babies buried in the same grave, most of them stillborn.

"It's a privilege to be able to show people where their babies are [but] it's sad that they've not known," he says.

He believes the authorities at the time had been showing "a sort of stiff upper lip as they thought it was right for families to just get on with their lives".

He is encouraging others to come forward and access the records by providing the mother's full name at the time of the birth, their address and the date of their baby's death.

When Julie found where her son was buried, she spent every day at his graveside for an entire year

Julie Harrington was also never told what happened to her baby boy, who was born on 8 December 1979.

The 61-year-old says she was given a brief glimpse of her son before he was taken from her.

She says she also thought "they'd thrown him away".

"I know they did ask my husband 'do you want us to take care of things?' but he didn't know what things because nothing had been said."

Julie, from Hollingworth, spent four years thinking her baby, who the couple named Martyn, had been incinerated as medical waste.

"You weren't given a birth certificate or a death certificate, because it didn't exist so you just shut it off," she says.

She says the grief only caught up with her when she subsequently gave birth to a healthy girl and she was referred for counselling.

Her counsellor then contacted a local priest who found where Julie's son had been buried, just a few miles from where she lived.

Julie then spent every day at his graveside for an entire year.

"I just felt so sad that he was there, happy that I'd found him and it was nice to be able to come as well," she says.

Amie Reece said her baby daughter Charlotte was "beautiful"

Clea Harmer, chief executive of stillbirth and neonatal death charity Sands, says Lilian and Julie's stories are something the organisation hears "very often from those who have been bereaved a long time ago".

"The idea was if you didn't let the mothers see the baby and you didn't talk about it, then you wouldn't upset her and she'd get over it very quickly," she says.

Clea says the experience of stillbirth is very different now than it was in the past.

She says historically, parents would be "equally devastated" and the grief that they experienced was the same, but the way that they were helped to cope with that grief was "so incredibly different".

Data from the Office for National Statistics shows that in 2021, the stillbirth rate in England rose to 4.2 in every 1,000 births, compared with 3.9 in 2020.

On 7 April 2015, Amie Reece, from Stockport, gave birth to a baby girl named Charlotte.

She says memories of the birth remained vivid.

"There was no crying," she says, adding: "It's the silence in the room that weighs heavy."

However, unlike Lilian and Julie, Amie and her husband Ed were able to spend time with their daughter and say goodbye, making hand and foot prints, reading a book to her and cradling her in their arms.

"My husband bathed her [which] was lovely as he was really looking forward to bath times," she says.

"We picked out an outfit that we wanted to take her home in, so we dressed her in that.

"She had name bands as well - everything felt as if she was ours and we weren't rushed.

"We were told we could spend as much time as we wanted with her."

A funeral was also held for Charlotte.

Since then, Amie, who also has two boys, has set up a support group with the help of Sands for those who have endured similar heartache.

"I've got those memories and they are good memories," she says.

"Yes, they're sad - but I was still able to feel like a mum.

"I think that was the biggest thing for me, because she was my first and I was leaving hospital without a child but I was still a mum."

For Lilian, just having the chance to say goodbye offers a little solace.

"Just recently, I've spent a lot of time upset every time I've thought about it," she says.

"But I'm a bit better today, I think, because he's here and it's made a difference."

Why not follow BBC North West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external? You can also send story ideas to northwest.newsonline@bbc.co.uk

Related topics

- Published9 March 2022

- Published14 October 2021

- Published10 October 2021

- Published28 September 2021

- Published27 November 2020

- Published22 June 2017