Commonwealth Games 2002: Ex-council boss proud of legacy

- Published

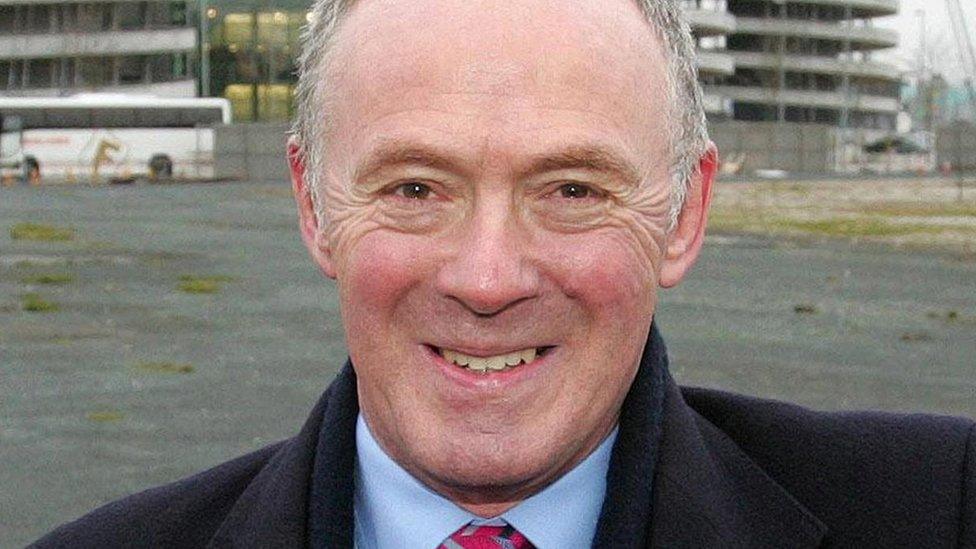

Sir Howard Bernstein said east Manchester had had a "remarkable regeneration" since the games

The £300m cost of Manchester's Commonwealth Games was "undoubtedly" worth it, as it led to "one of the most successful regeneration stories" ever seen, the man behind it has said.

Sir Howard Bernstein, who was the council's chief executive, said the event was an "important part" in the city's "evolution" after the 1996 bomb.

He said it was not a "panacea", but it brought growth, jobs and civic pride.

"We should celebrate that and continue to build on that success," he said.

The games saw the building of major new sports venues, including the Manchester Aquatics Centre, the National Squash Centre and the City of Manchester Stadium, which became the home to Premier League champions Manchester City.

Away from sport, it also led to the areas around those venues, particularly in Beswick, Ardwick, Ancoats and New Islington, being transformed, with new homes, schools, shops and amenities being built in the two decades since the event.

'Significant economic growth'

Sir Howard, whose endeavours earned him a knighthood a year after the games, said it built on Manchester's existing international recognition in sport and culture and paved the way for the city hosting major events, such as the Manchester International Festival, and being home to the likes of British Cycling and the Rugby Football League.

He said more than anything though, it acted as a springboard for a "remarkable regeneration" of east Manchester.

"It was not a panacea; there are still challenges [but] people are choosing to live there and businesses are choosing to locate there," he said.

The City of Manchester Stadium was the centre of a huge development, known as Sportcity

Once the home of the city's heavy industries, much of the area was derelict by the 1980s.

Sir Howard said after the games, there was "significant economic growth and development, thousands of jobs, better housing and [it] fostered civic pride to people in the city".

"East Manchester is probably one of the most successful regeneration stories to be found anywhere in the western hemisphere," he said.

"We should celebrate that and continue to build on that success."

'Not an accident'

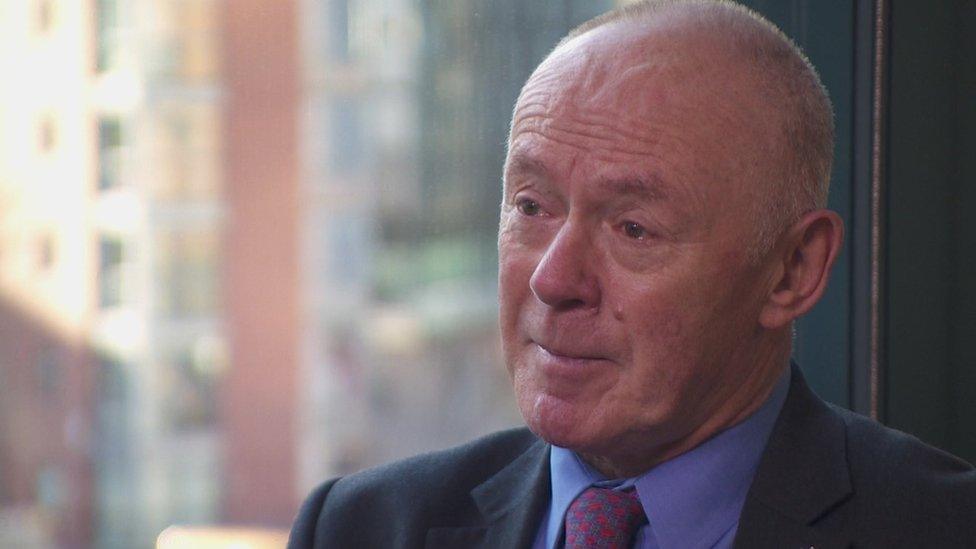

Sir Richard Leese, who led Manchester City Council from 1996 to 2021, said it was possible to still see the impact the event had on the city, as the "sporting and cultural legacy is enormous".

He said the sporting facilities and events like the Great Manchester Run, which came out of the games, were the "catalyst" to east Manchester's regeneration".

He said before the event, the area did not have a high school or a mainstream supermarket, leaving people without transport having "to pay premium prices at local convenience stores", but the opening of Asda at Eastlands, which was followed by other supermarkets, had fostered "a positive community for people who want to live there".

Sir Ricahrd said the fact people still spoke about the games showed how "very special" they were

He said the legacy "was not an accident" and the games were actually "built into a regeneration plan" which started seven years beforehand.

They were "baked into a broader strategy" and not a "one-off" event where everyone has a "fantastic time" and goes home, he added.

He said the council had looked at regenerating the area since the 1980s, but work had been stalled by the banking crash and recession in 2008.

"In the last four to five years, it has got going again and it is fantastic to see [but there is] still much to do," he said.

However, he said the fact people from Manchester still talk about the games 20 years on "with immense pride" showed how "very special" they were.

Since the games, east Manchester has seen many new buildings go up, such as the East Manchester Academy

Community charity 4CT has run the Grange Community Resource Centre in Beswick since 2005.

Its chief executive Claire Evans, who has worked in east Manchester since 1996, said the regeneration had "massively improved the area physically, socially and economically".

She said some businesses had thrived thanks to the arrival of Manchester City and the increase in footfall on matchdays and some measures, such as alley gating, had cut crimes like muggings.

However, she said "some amazing things couldn't be sustained", such as the community warden patrols which supported the police, and not all residents were happy with the transformation.

She said some were "put out" by the investment being concentrated on social housing, as well as stadium traffic and noise.

Dr Chris Mackintosh, senior lecturer in sport development at Manchester Metropolitan University's Institute of Sport said initial indications were that the legacy of the games "did not lead to an increase in sporting activity in the area".

"However, the economic regeneration for new East Manchester led to new local pools, increased community sport and infrastructure for volunteering, coaching and physical activity," he said.

He added that the Sportcity development around the City of Manchester Stadium was "an iconic success story for Manchester and the UK economy".

"Provision of wider transport, leisure, retail and sport economy multiplier effects from events have provided a blueprint for other bids," he said.

"New East Manchester still remains an area with stubborn social inequalities and poverty, which remains a challenge for all agencies [but] sport and physical activity's multiple roles in addressing health problems is starting to become a reality.

"The residents of 2022 now face many of the same issues as in 2002, but many infrastructure and initiative innovations are far better placed to deal with the complexity and ingrained economic and social divides."

Why not follow BBC North West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external? You can also send story ideas to northwest.newsonline@bbc.co.uk

- Published2 December 2021

- Published2 April 2017

- Published26 July 2012