James Chadwick: The Brit chief who worked on the nuclear bomb

- Published

James Chadwick won a Nobel Prize for his discovery of the neutron

The Oppenheimer movie has inevitably ignited interest in one of the most contentious episodes of modern history - the birth of a nuclear weapon which unleashed unprecedented destruction.

While the film focuses on the eponymous American physicist spearheading Allied efforts to make the atomic bomb, the team also involved British Nobel Prize winner James Chadwick.

Yet little is known about Chadwick when compared to his peers, whose names read like a who's who of school science lessons.

The shy but steely scientist is credited with discovering the neutron, before going on to lead the British contingent in the Manhattan Project, that was set up to build the atomic bomb.

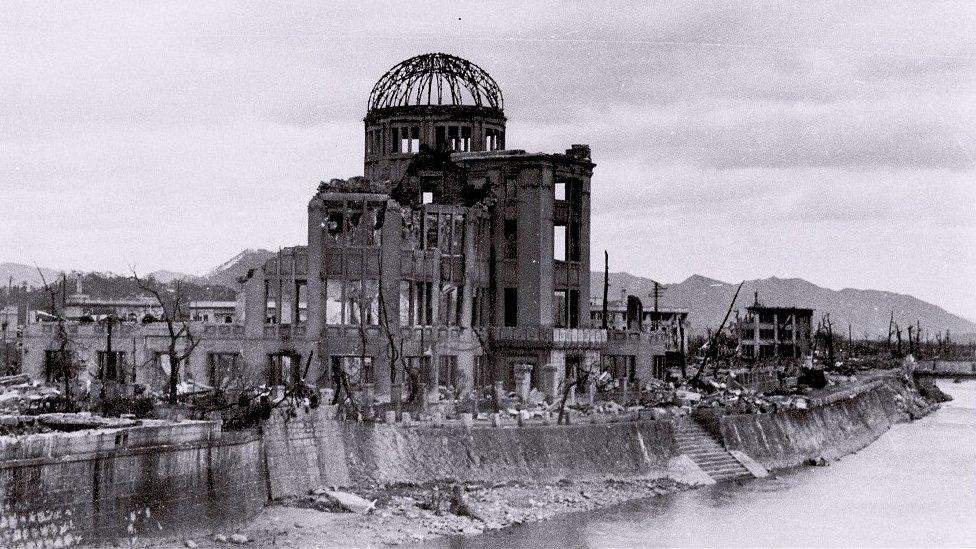

As World War Two drew to a close, American bombers would drop the devices over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, instantaneously killing more than 100,000 people.

During their development, Chadwick was the only non-American with access to all of the group's research and production plants, according to experts.

He famously admitted his "only remedy, external" on realising the inevitability of the nuclear bomb was to take sleeping pills, which he ended up doing every night for more than 28 years.

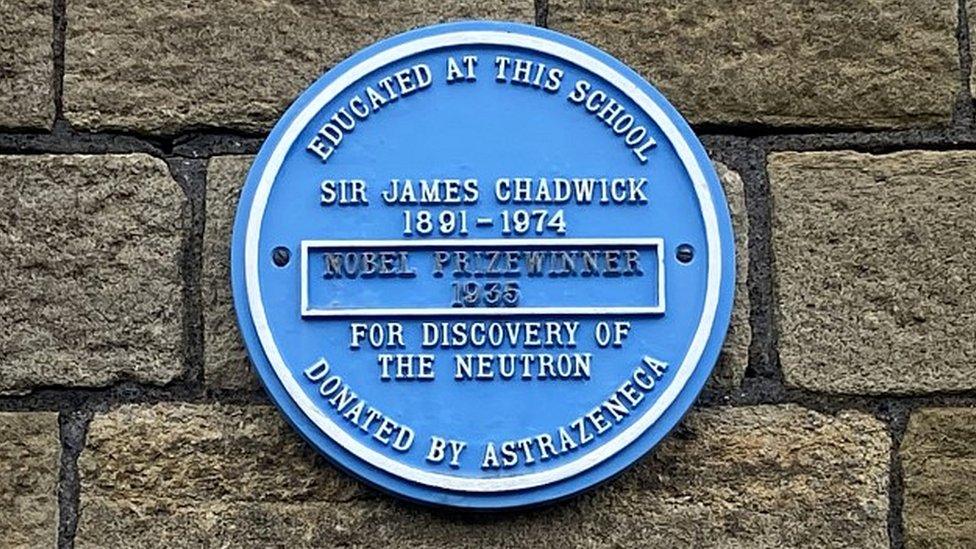

James Chadwick's school in Cheshire now has a blue plaque in tribute to him

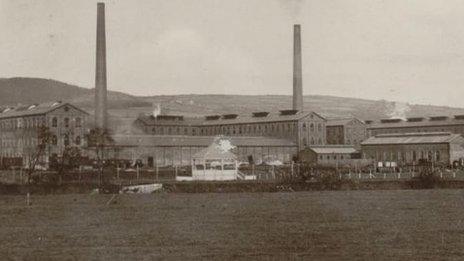

Before his tenure at Los Alamos, Chadwick's career had developed in Manchester, often described as the birthplace of nuclear physics.

The city had become a hub of science and engineering from the onset of the Industrial Revolution in the mid-18th Century.

But Chadwick's origins 20 miles away never indicated what he would later achieve.

"He was not from any kind of wealthy background," says Dr James Sumner, a historian of technology at the University of Manchester.

"He was certainly not from a traditional academic background."

Born in the Cheshire village of Bollington in 1891, Chadwick himself described his family as poor, with his father failing to set up a business in Manchester.

During an interview later in life, he admitted losing contact with a younger brother, adding: "I'm afraid I don't have a great family feeling."

He "didn't take school very seriously" and recalled playing truant one day with his friend - the headmaster's son - "to go bird-nesting".

"I have quite a vivid memory of being caned very severely for it."

Despite this less than promising start, he later moved to a school in Manchester where he benefited from "extremely good" teaching and gained a university scholarship.

The University of Manchester became known as the birthplace of nuclear physics

"Manchester then, as now, is a very progressive city indeed," Chadwick recalled, saying he wanted to study mathematics with "no intention whatever of reading physics".

But a mix-up, which involved sitting on the wrong interview bench and being "too shy" to ask for a subject change, inadvertently led to a successful career in physics.

He studied under Prof Ernest Rutherford, the Nobel Prize-winning New Zealander whose model of the atom is still used in schools worldwide.

"You don't let undergraduate students near the monumental, partly because the professors want all the relevant glory for themselves," says Dr Sumner.

"At that time, there were just far fewer physicists and there was more glory to go around, so people like Chadwick could make a difference very early on."

Chadwick (seated left) was one of Rutherford's (seated right) prolific students, along with Hans Geiger (seated centre) and Otto Hahn (standing right), who won a Nobel Prize for discovering nuclear fission

Manchester had been steadily attracting scientific prestige after John Dalton pioneered studies in atomic theory and colour blindness, while fellow student James Joule became a household name after his work in energy conservation.

"Once you've got a big name there, everyone else goes in and makes more discoveries," says Dr William Bodel, who researches nuclear technology at the university in Manchester.

Others to pass through the university included J.J. Thomson - who is credited with discovering the electron - quantum physicist Neils Bohr and Hans Geiger, co-inventor of the radiation counter.

"Chadwick was one of several who did forefront cutting edge research," says Dr Sumner.

"He is publishing forefront discoveries in the hot new science of atomic physics and that's really when his career took off."

He met Albert Einstein on occasions at a Berlin laboratory, where Chadwick was undertaking research with Geiger.

But after World War One broke out, he was imprisoned at a camp when all Englishmen were interned. He still managed to pursue his scientific interests, making a magnet as the German officers - whom he described as "extremely lenient" - turned a blind eye.

Chadwick (left) gained the trust of Lt General Leslie Groves (right), who was in charge of the Manhattan Project

On returning to Manchester much weakened and poorer after the war, he was offered work by Rutherford and the pair soon took up opportunities at the University of Cambridge.

His life underwent another change in 1925, when he married Aileen Stewart-Brown in Liverpool and two years later, the couple had twin daughters.

As the science of physics continued to develop, Chadwick proved the existence of the neutron in the early 1930s after some speculative - or "quite silly" as he called it - experiments, following years of believing it was a main constituent of the nucleus.

"When I did the experiments, as I did off and on, they were done at odd moments and sometimes when nobody was about," he said.

Yet Dr Bodel describes the discovery as "fundamental enough to teach to school children".

"Before him, it was known there was an extra particle, but it was difficult to detect."

Chadwick said "it hadn't crossed my mind" that the breakthrough would earn him the 1935 Nobel Prize for Physics but, in his typically succinct way, he said he was "naturally, extremely pleased".

Oppenheimer features Matt Damon as Lt Gen Groves and Cillian Murphy in the lead role

The prize came at a parting of the ways with his mentor Rutherford, as they differed about new equipment to advance their research.

Chadwick took up the offer as chair of physics at the University of Liverpool, saying he also wanted "more contact with other people with different interests".

Following the outbreak of another world war, his expertise saw him join a British working group to study the possibility of developing a nuclear weapon.

A destructive legacy

Hiroshima was targeted because of its military value as the headquarters of the Japanese Second Army

The US declared war on Japan after the latter bombed an American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii in December 1941, following a decade of deteriorating relations

Four days later, Nazi Germany and Italy declared war on the US - two years after World War Two began

Some months before the start of the conflict in 1939, scientists confirmed the discovery of nuclear fission, where the nucleus splits while releasing huge amounts of energy

Efforts were undertaken to use its force for military purposes, culminating in the "airbursts" of atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945 respectively

On 10 August, Japan offered to surrender, thus bringing six years of war to an end

Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica

In 1943, Chadwick travelled as head of the British mission to Los Alamos in the US, where scientists were developing the first atomic bomb.

But he felt "much more needed in Washington to keep in touch with our people there and to see what was happening in different places".

He worked closely with project chief Lt General Leslie Groves, played in the film by Matt Damon, and spoke rarely about laboratory director Oppenheimer or "Oppie" as he called him.

However, there were concerns "other countries would take up the business", according to Chadwick.

"I was quite sure, you see, that the Russians could not be far behind in knowing about the project."

James Chadwick died at the age of 82

Chadwick believed British participation was "helpful", even though "perhaps we had not many contributions to make".

The explosions over Hiroshima and Nagasaki killed more than 100,000 people, with more dying from the impact by the end of 1945.

"It completely changed the way we operate," says Dr Bodel. "The world was not the same after the Hiroshima bomb. We can't underestimate their contribution."

Despite Chadwick's discomfort at the devastating impact, he went on to lobby for the UK to have its own nuclear arsenal after the war.

"I don't have any doubts that the bomb had to be used. And I don't feel any guilt in having taken part in producing it. Why should I? Far worse things happened than that — perhaps not many," he said.

Additional research by Isobel Fry

Why not follow BBC North West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external? You can also send story ideas to northwest.newsonline@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published19 July 2023

- Published6 August 2020

- Published9 August 2015

- Published6 August 2015

- Published4 July 2015