Moby Dick on the Mersey: The history of whaling in Liverpool

- Published

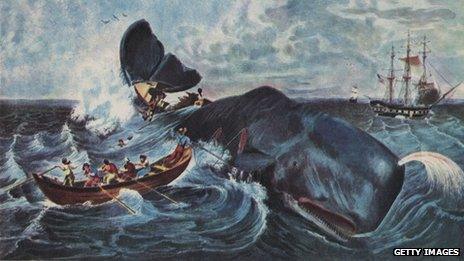

Sperm whales like Herman Melville's Moby Dick were hunted for their oil

At the Moby Dick on the Mersey festival, external (4 - 6 May), Liverpool celebrates its links to the author Herman Melville with a marathon reading of his novel. Dr Chris Routledge, from the University of Liverpool, reveals the city was once a key whaling port.

From slavery and cotton to Irish emigration and shipbuilding, Liverpool is key to some of the most important maritime stories in British history.

But there is one important trade for which Liverpool is not well known: Arctic whaling.

In the late 18th Century, small numbers of British ships began hunting Bowhead whales for their oil around Greenland and Spitsbergen alongside a huge Dutch fleet.

Worried that Britain was too reliant on foreign oil, the British government doubled the whalers' bounty, or subsidy, to 40 shillings per ship ton in 1750 to encourage the development of a domestic whaling fleet.

Famous whaling ports like Hull and Whitby reached their peak in the early 19th Century, but Liverpool's whaling heyday was from around 1775 to 1790, possibly because the supply of oil from the American colonies had been cut off by the revolutionary wars.

From their base in the newly-opened Queen's Dock, 21 Liverpool whale ships sailed for the Arctic in March 1788.

They returned at the end of the summer with a total of 76 whales. By comparison the Whitby fleet numbered 20 ships that year.

Liverpool was not an ideal port for Arctic whaling - the prevailing westerly wind often prevented ships leaving the Mersey for days at a time and the short Arctic summer meant that whalers had no time to lose.

Even so, whaling was important to Liverpool's economy. With a crew of between 40 and 50 per ship, around 1,000 Liverpool men went to the Arctic each year.

Their work supported oil traders, bone cutters, stay makers and many others who turned whales into fuel, lubricants, and consumer items such as umbrellas, corsets, knife handles and even furniture.

Moby Dick

As Hull, Whitby, Peterhead, and other northern ports expanded their whaling fleets, Liverpool's began a slow decline.

By 1820, when Hull's 60 ships earned the vast sum of over £318,000 between them, only three whalers sailed from the Mersey.

But the brief story of whaling in Liverpool has one final flourish.

In 1819 William Scoresby Jr, one of the most successful whalers and Arctic explorers of his generation, moved from Whitby to Liverpool to oversee the construction of a state-of-the-art whale ship, Baffin, by shipwrights Mottershead and Hayes.

Scoresby, the son of a whale ship commander, first went to the Arctic in 1800 at the age of 10, as a stowaway on his father's ship.

At 17, he began attending Edinburgh University in the winters between whaling voyages and soon made a name for himself as an Arctic scientist.

William Scoresby Jr, one of the most successful whalers of his generation

In 1820, he published An Account of the Arctic Regions, a standard text on the Arctic for a century, and one of Herman Melville's factual sources in writing Moby Dick (1851).

Whaling allowed Scoresby to sail to the Arctic, but catching whales got in the way of his research; the Admiralty refused to support him.

The solution came from Liverpool's financiers, in particular his friend William Rathbone.

Rathbone insured the Baffin on very generous terms, allowing Scoresby to take more risks with the ship than he might have done on a routine whaling voyage.

The result, in 1822, was an accurate chart of the East coast of Greenland. Scoresby called it the 'Liverpool Coast' and named islands and inlets after his friends in the city. Most of them were renamed by later expeditions.

Scoresby's 1823 voyage was the last Arctic whaling voyage from Liverpool.

He retired from whaling to become a clergyman and campaigner for better conditions and education for factory workers. He continued his scientific research into magnetism and electricity right up to his death in 1857.

The Baffin, the last Liverpool whaler, transferred to Peterhead in 1825 and was lost in the Davis Strait in 1830.

Dr Chris Routledge is Programme Director for Continuing Education in English Literature and Language at the University of Liverpool and a freelance writer and editor. He is working on a book about William Scoresby Jr. and Greenland's Liverpool Coast.

- Published31 January 2013

- Published26 October 2012

- Published2 July 2012