Liverpool students aim for world's fastest bike record with ARION1

- Published

No blood, but there was sweat and probably tears from the candidates undergoing testing

Can man and machine combine with science and engineering to produce the world's fastest human-powered vehicle? We visit the test lab in Liverpool where peak design meets peak fitness and where cycling dreams are distilled from sweat and tears.

Despite the triumphs of British cycling in recent years, the country has never held the record for the fastest bike.

But the University of Liverpool Velocipede Team, external is hoping to push the limits of two-wheeled endeavour to a new level with a NASA-style bicycle and the ultimate human engine.

In the last few weeks, they have tested 35 candidates - including former cycling champion Rob Hayles - in their attempt to break the male and female records for a human-powered vehicle.

The students are designing a velocipede - a "fancy name" for a bike, according to team leader Benjamin Hogan - designed to propel its rider at a speed in excess of 83 mph (134 km/h) at an event in September next year.

To put this in context, the world's top cyclists in the Tour de France, external hit a top speed of around 60 mph (100 km/h) - and that's downhill.

As part of the selection process, prospective riders have to cycle at their maximum speed in two "peak power" tests of 10 and 30 seconds. They then undergo an endurance test in which resistance is steadily increased until the rider can no longer continue.

The rider can only see where he or she is are going via an external camera

Three-time Olympic medallist Rob Hayles, was one of those who took part in the final day of fitness testing at Liverpool John Moores University.

After a "grim" endurance test, he managed to get enough breath back to say it "rated pretty high on the pain scale".

He even said the exhaustive procedure has forced him back to peak fitness after retiring from professional cycling in 2011.

With its resemblance to a space pod, missile or pocket Tippex, Mr Hogan admits ARION1 doesn't look like a conventional bicycle.

But the specific design of the £60,000 velocipede, made of carbon fibre and Kevlar, is "top secret".

Fit like a glove

"It has two wheels, it has steering, it has a seat and it has brakes. It has all the components that a normal bicycle would have but they've just been rearranged," the engineering student says.

"They're cycling in what's called a recumbent position, where the rider is sort of lying down on his back."

Wedged in the enclosed pod, the rider will only be able see where they're going through a monitor linked to an exterior camera.

The velocipede should fit the cyclist like a glove so he or she can combat the "main enemies" of aerodynamic drag and cut through the air, Mr Hogan adds.

"This competition is purely human-powered - no engine or anything like that [...] we don't have much power to play with so we have to make it as efficient and aerodynamic as possible."

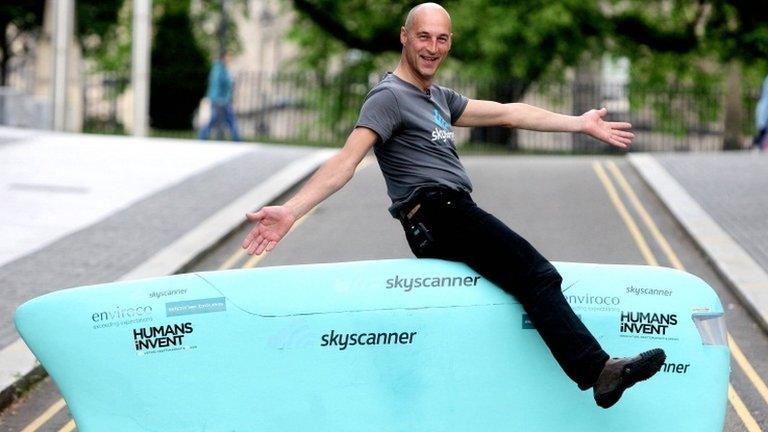

Former Olympic medallist Rob Hayles says the selection process for the record attempt is "grim"

The students reckon their "innovative" ventilation through the velocipede's nose - to cool the 45-50C heat inside the bike - will have them leading the field.

Better than a Bugatti

Computer modelling to improve the bike's aerodynamics and sensors placed on the rider will ensure that "human and machine work in harmony", says Mr Hogan.

He claims the bike, named ARION1, is "about 40 times more aerodynamic than a Bugatti Veyron sports car".

It will compete against other contraptions next September at the World Human Power Speed Challenge, external, held annually for 14 years in Nevada.

One of the smoothest roads in the world allows competitors to accelerate over four miles (6.4 km) to a maximum velocity before being timed over a 200m distance.

The current male world record stands at 83.13 mph and the fastest speed by a woman at 75.69 mph (122 km/h).

Graeme Obree, now aged 49, won world titles for the 4km pursuit in 1993 and 1995

The record attempt has seen all three universities in Liverpool collaborate for the first time.

Around 16 mechanical engineering students from the University of Liverpool are working with sport science undergraduates and staff at Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) and Hope University.

"If you look at it this way, the University of Liverpool is providing the bolts, and LJMU and Hope are providing the engine - the humans going inside it," says Mr Hogan.

Quest for speed

The engineering students decided to build the velocipede for their degree project, after teams from TU Delft and VU Amsterdam universities in the Netherlands set the record last year.

"We're renowned around the world for our cycling capabilities - [so] why can't we do this?" says Mr Hogan.

"The thing that's powering this is a set of legs, and I wouldn't want any other than a British cyclist pedalling this thing because it's a tall order."

But the Liverpool team aren't the only Brits going for glory next year.

After failing to break the record in 2013, former world champion Graeme Obree, also known as the Flying Scotsman, is building a bike, external he hopes will propel his son Jamie to victory.

However Mr Hogan is confident about the Liverpool attempt and hopes universities around the world will take up "this ultimate quest for speed".

"Before the Netherlands' students broke the record, people built the bikes in their back sheds.

"It was backyard engineering - we are just at the point where modern technology and science and engineering are taking over."

- Published10 September 2013

- Published14 September 2013

- Attribution

- Published31 October 2011