How does black hair reflect black history?

- Published

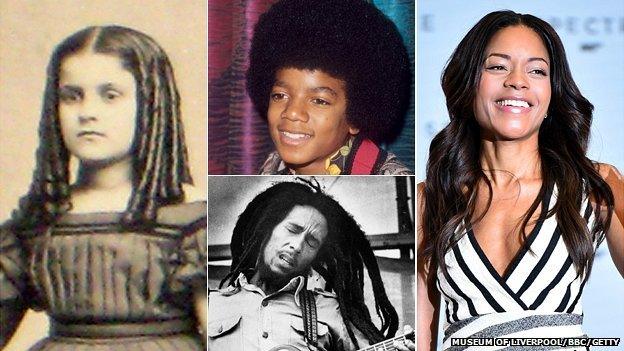

Black hairstyles are the subject of a new exhibition - (from left) a freed slave girl, music stars Michael Jackson (top) and Bob Marley, and James Bond actress Naomie Harris

Black hair has been an integral feature of black history - from African tribal styles to dreadlocks and the afro. As an exhibition in Liverpool explores the significance of hair in black culture, BBC News takes a look at some of the key styles.

African origins

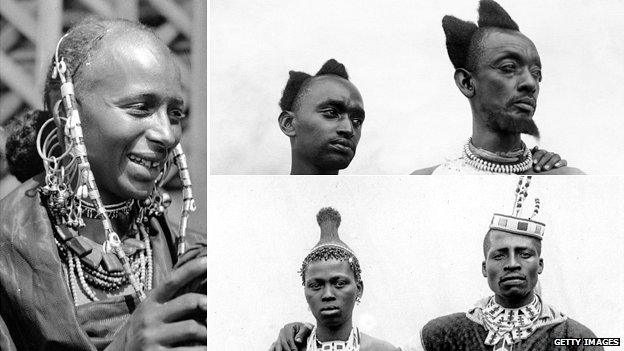

Headdresses and hairstyles indicated status and identities across Africa, including Cameroon (left), Ivory Coast (top) and southern Africa

In early African civilisations, hairstyles could indicate a person's family background, tribe and social status.

"Just about everything about a person's identity could be learned by looking at the hair," says journalist Lori Tharps, who co-wrote the book Hair Story about the history of black hair.

When men from the Wolof tribe (in modern Senegal and The Gambia) went to war they wore a braided style, she explains. While a woman in mourning would either not "do" her hair or adopt a subdued style.

"What's more, many believed that hair, given its close location to the skies, was the conduit for spiritual interaction with God."

Slavery and emancipation

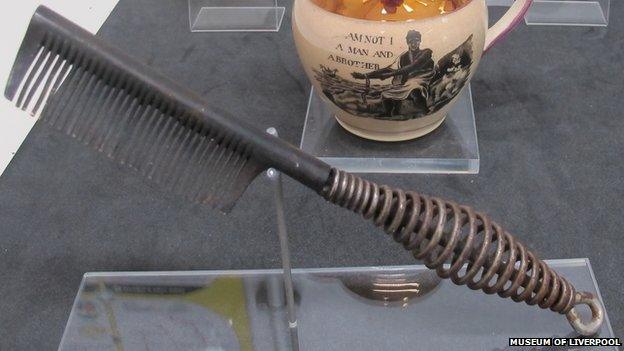

A comb and jug from the post-emancipation period at the exhibition

It is estimated that 11,640,000 Africans left the continent between the 16th and 20th Centuries, external due to the transatlantic slave trade.

These slaves took many of their African customs with them, including their specially-designed combs.

"Their key is the [bigger] width between the teeth because African-type hair is very fragile," says Dr Sally-Ann Ashton, who curated an afro comb exhibition at Cambridge's Fitzwilliam Museum in 2013.

"Out of all the different [hair] types, it's probably the most fragile so if you're yanking a fine tooth comb through it, you're going to do an awful lot of damage."

During the 19th Century, slavery was abolished in much of the world, including the United States in 1865. However, many black people felt pressure to fit in with mainstream white society and adjusted their hair accordingly.

"Black people felt compelled to smoothen their hair and texture to fit in easier, and to move in society better and in camouflage almost," says exhibition producer Aaryn Lynch.

Many black people, such as entertainer Josephine Baker, used products to straighten their hair

"I've nicknamed the post-emancipation era 'the great oppression' because that's when black people had to go through really intensive methods to smooth their hair.

"Men and women would put their hair in a hot chemical mixture that would almost burn their scalp, so they could comb it back and make it look more European and silky."

The industry grew to the extent that black entrepreneur Madame CJ Walker, who sold hair growth products, shampoos and ointments aimed at the African-American market, was recorded as the first self-made millionairess in the US by Guinness World Records, external.

Civil rights era

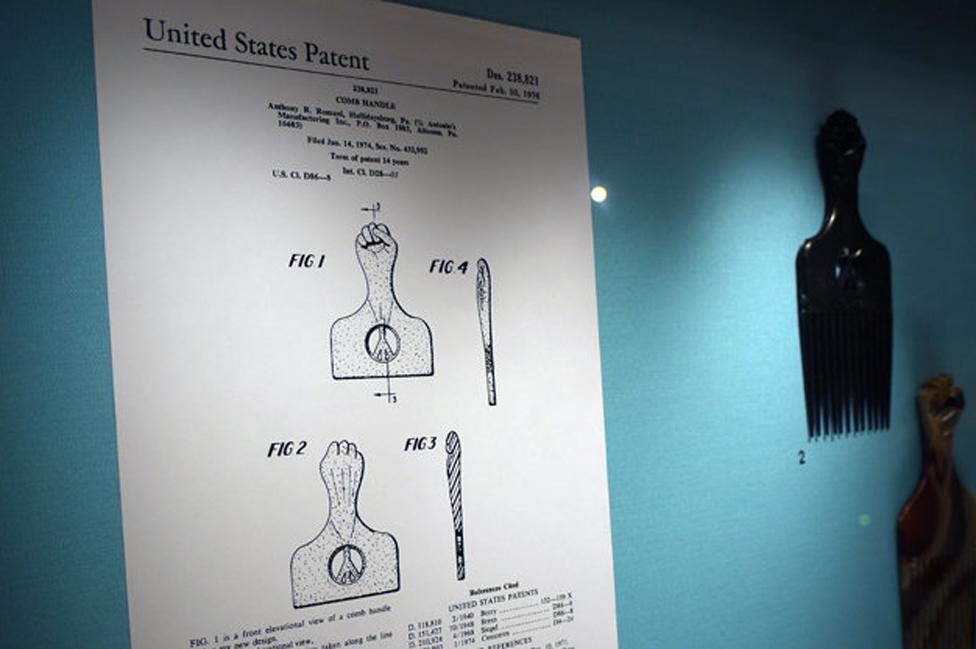

The clenched fist comb symbolised black pride along with afros

The afro hair style, which emerged in the 1960s during the civil rights movement, was "a symbol of rebellion, pride and empowerment", says Mr Lynch.

As black people protested against racial segregation and oppression, the eye-catching style took off - an assertion of black identity in contrast to previous trends inspired by mainstream white fashions. And with it the African (or afro) comb re-emerged.

"It was never lost in Africa of course," says Dr Ashton. "But this was with the advent of black power and politics.

"The afro hairstyle became very popular and for that you need a long kind of pick… it's quite high-maintenance."

In response to the racial politics of the time, the fist comb - with a handle shaped like the black power salute - was designed in the 1970s.

"A lot of people who were born in the 1980s and 90s think [the salute] is associated with Nelson Mandela, which it's not - it's just that he happened to use that salute when he was released from prison," says Dr Ashton.

Roots

A Liverpudlian woman sports dreadlocks around 1990

In the 1930s, Rastafari theology developed in Jamaica from the ideas of Marcus Garvey, a political activist who wanted to improve the status of his fellow blacks.

Believers are forbidden to cut their hair and instead twist it into dreadlocks. It is not clear where the style originates from, although there are references in the Old Testament and the Hindu deity Shiva is also sometimes depicted wearing them.

The profile of the religion grew significantly in the latter half of the 20th Century, as the "roots" movement developed, harking back to the origins of African-Caribbean culture.

Its profile increased following the success of musician Bob Marley in the 1970s, with dreadlocks becoming a common sight in British cities.

Along with the afro, dreadlocks remain the most distinctive black hair style among other ethnic groups.

"The problem remains however, that while we may style our hair to reflect our own individual choices, our hair is still being interpreted by a white mainstream gaze and that interpretation is often wrong as well as racist," author Ms Tharps says.

"Too many people still make assumptions that an afro implies some sort of militancy or that wearing dreadlocks means a predilection for smoking pot."

Contemporary culture

The singer Beyoncé popularised the glitter weave after attending the 2010 Grammys, while men - like actors David Oyelowo and Will Smith - often opt for the shaven or shorn look

Black hair care is now a major industry, conservatively estimated to be worth about £530m, external ($774m) last year.

However, there is often debate about whether some trends still symbolise a desire to fit in with a mainstream Western look, Mr Lynch says.

"Do we still feel like we're compelled to appropriate white culture or is it now a choice, whatever's convenient, whatever's in fashion?"

Among women, hair extensions known as weaves have been popular but there is also a reported revival in natural hair - usually interpreted as styles not altered by chemicals.

"It's a really important movement that's going on and in America it's a lot bigger than it's over here," says Dr Ashton.

"So if you go to the States, you see lots of African-American women with natural hair - you're starting to see that more in this country but there's still nowhere near the same number in Britain as there are in the States."

Many are browsing online to learn more about natural hair care - knowledge of which declined among black communities in the West after slavery.

But changes in working patterns in the past 60 years, especially for women, means there can be less time to spend on maintenance, says Dr Ashton.

"I think one thing a lot of non-black people don't realise is just how much maintenance African-type hair is. If somebody says I'm washing my hair tonight, it can be like a three-hour job - it's an excuse for why you wouldn't go out."

HAIR runs until 31 August at the Museum of Liverpool.

Liverpool's black history

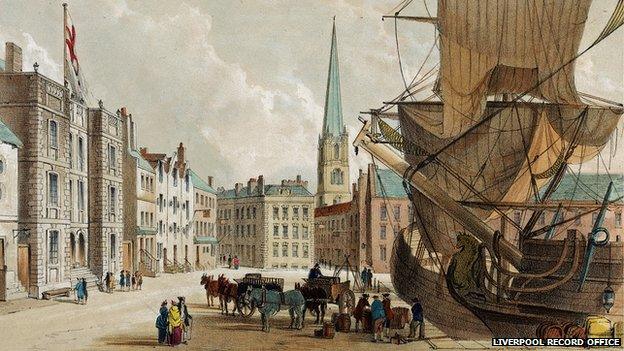

The city became the centre of the Atlantic slave trade in the late 18th Century

Liverpool's black community began with the slave trade and is among the oldest in Europe

In the 1750s, black residents of the city included sailors, freed slaves and the student sons of African rulers

By the 1780s, the port was seen as the European capital of the transatlantic slave trade with profits boosting the city's development

In total, Liverpool ships transported some 1.5m slaves from Africa

After World War One, 5,000 black people lived in Liverpool but tensions and riots erupted as servicemen returned looking for jobs

Riots also broke out in inner-city Toxteth in 1981 involving black and white youths against the police following economic and racial problems

- Published16 March 2015

- Published11 December 2014

- Published14 February 2013

- Published6 June 2014