Three Queens: How Cunard transformed travel

- Published

Cunard's ocean liners were at the forefront of a boom in transatlantic travel, which began in the mid 19th Century

Three famous ocean liners are meeting in Liverpool for a majestic display to mark the 175th anniversary of the shipping line Cunard, which revolutionised transatlantic travel in the 19th Century.

The year is 1842 and Cunard's impressive new steam ship, the Britannia, is making a stormy Atlantic crossing from Liverpool to Boston.

In the middle of the night, a group of nervous female passengers, lurching from side to side, are approached by a young man who offers them a calming drink of brandy and water.

However, he trips and struggles to reach them as the listing vessel leaves them staggering and falling about the cabin.

That man was one Charles Dickens, making the voyage with his wife and a female servant.

At the height of his fame on both sides of the Atlantic, according to records at the University of Liverpool, he paid the princely sum of £20 and nine shillings for his ticket - the equivalent of more than £1,600 ($2,500) in today's money.

For that amount you might expect the height of luxury - but the reality was very different.

Conditions were basic and Dickens did not seem a very happy passenger.

Describing his experiences in American Notes, the novelist said his companions were in "ecstasies of fear".

"By the time I did catch them, the brandy-and-water was diminished, by constant spilling, to a tea-spoonful," he added.

The Queen Mary 2, the Queen Elizabeth and Queen Victoria are meeting for a display on the River Mersey

The Cunard shipping company was founded in Liverpool and its liners retain close ties with the city

But although these early journeys could be unpleasant, steam ships were transforming transatlantic travel in the mid-19th Century.

They added speed and safety to journeys which, until that time, were made on far less reliable - and often dangerous - sailing ships.

Cunard, with its headquarters in Liverpool, was at the forefront of this oceanic revolution.

It was founded in 1839 by Samuel Cunard, a Canadian businessman who won the first British steamship contract to deliver mail across the Atlantic. For the first time, posting a letter to America was not simply a fanciful gamble.

The company then embraced passengers and grew rapidly. Within 30 years it was employing some 11,500 people and had amassed a fleet of 46 ships.

It was said that everyone in Liverpool either worked or knew someone who worked for Cunard.

The Cunard Building, which remains today as one of Liverpool's "Three Graces", was the company's headquarters

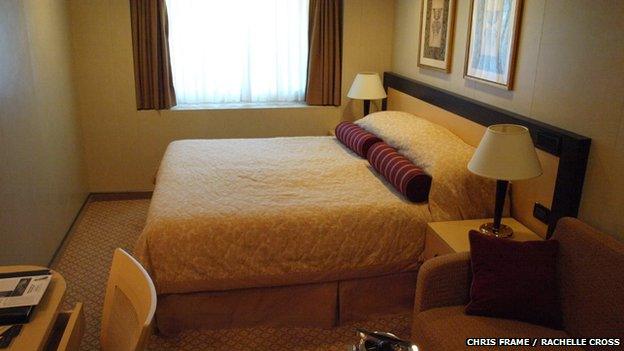

A standard cabin on the Queen Victoria

Cunard would eventually become a byword for luxury, but not for quite some time.

"It is said that a passenger once complained to a ship's officer that water was coming down the stairs, and he replied 'madam, we only worry when water is coming up the stairs," says historian Michael Gallagher.

"It was a very conservative company and safety was the priority. The reputation still stands - in 175 years Cunard has never once been responsible for the loss of a single life.

"Cunard would always wait until new technology had been properly tested before adopting it, whereas other companies could be vulnerable to accidents with things like new propellers.

"But although the early voyages could be uncomfortable, you knew Cunard would get you there."

Author Chris Frame, who has co-written several books about Cunard ships, added: "Britannia and her sister ships had no refrigeration, so they carried livestock aboard for fresh produce - cows for milk and chickens for eggs and meat.

"The ships also used to carry a cat, which was there to handle the rats."

Cunard at 175: Facts and figures

Since the first scheduled service across the Atlantic, Cunard ships have crossed and re-crossed the Atlantic, in peace and war, without fail every year

More than 109,000 bottles of red wine are consumed every year on board Queen Victoria

The annual sugar consumption on Queen Mary 2 is enough to make eight million scones

Britannia was a reasonable sized ship for her day, but Mr Frame said things have come a long way since then.

"The Britannia could fit inside the Queen Mary 2's main restaurant. That gives you a sense of how large ships have become."

The company soon became a household name, not least due to the famous role played by the Carpathia, the Cunard ship which helped rescue hundreds of survivors during the sinking of the Titanic in 1912.

In another disaster three years later, Cunard's Lusitania was torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat, causing the deaths of 1,198 passengers and crew. It was one of the biggest outrages of World War One. Carpathia was also lost in the conflict.

In 1919, Cunard ships began operating mostly from Southampton, taking advantage of the port's more favourable tidal and navigational bearing.

By this time, the ships offered a much smoother, sumptuous service for passengers and were commonly referred to as "floating palaces".

In 1940, the newly launched Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth were painted grey and called up for the war effort.

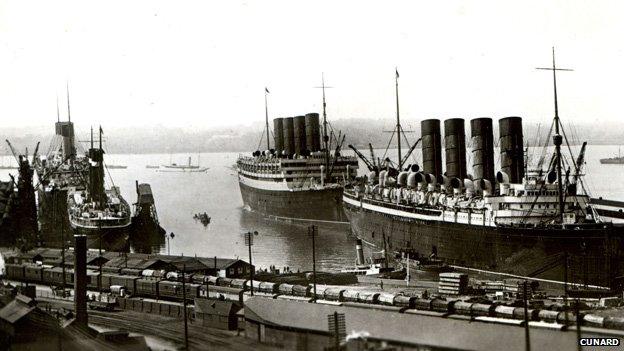

In 1919 the Mauretania inaugurated Cunard's new express service from Southampton to New York.

They transported more than a million troops including thousands of American GIs from the United States to the UK. They would go on to prove decisive during the D-Day invasion.

Hitler offered his U-boat captains the equivalent of $250,000 and the Knight's Cross to anyone who sunk either ship - about $4m (£6,250,000) in modern money.

"Winston Churchill said the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth helped shorten the war by at least a year. You don't get a bigger compliment than that," says Mr Gallagher.

"They were bringing over 15,000 troops every week ahead of D-Day. The Queen Mary still holds the record for the most people ever to be carried on a ship - 16,500."

The post-war boom years were also hugely profitable for Cunard, which by then was enjoying what is widely regarded as the golden age of ocean liner travel.

Not only were the ships making round-the-clock voyages to take American troops home, but also their new wives and families.

According to GI Brides author Nuala Calvi, by 1946 about 70,000 British women had married American soldiers, with many of them travelling to begin new lives in the US.

The Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth in Southampton shortly after World War Two

Ironically, it was the same post-war boom that prompted the gradual decline of the ocean liner, with the advent of modern air travel.

Before the war, aircraft posed little commercial threat to the industry. Most pre-war planes were noisy and vulnerable to bad weather. Few had the range needed for transoceanic flights, all were expensive and had very limited passenger capacities.

But as planes became bigger, safer, more popular and affordable, the need for regular, large-scale transatlantic liner crossings diminished. Passenger ships did not disappear but many began operating as cruise liners and struck deals with flight operators in order to survive.

"It certainly wasn't the end. In the 1980s for example, you could sail out to New York on the QE2 and fly back on Concorde," says Mr Gallagher. "Cunard actually bought more Concorde tickets than anyone else at the time in order to provide this service.

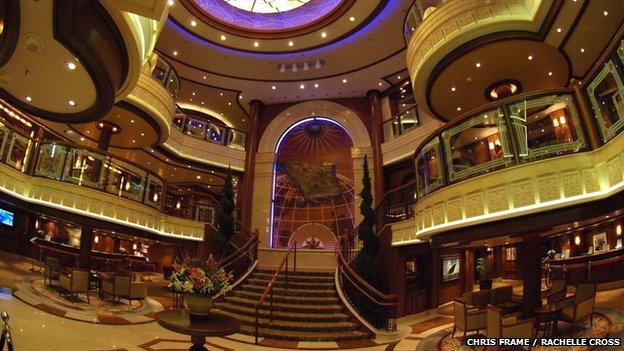

The lobby of the Queen Victoria

Author Mr Frame said: "Interestingly, there was a boom in cruise travel off the back of James Cameron's movie Titanic. People saw the romantic ocean voyage that was depicted in the early parts of the film and wanted to experience this romance for themselves.

"Today the line has three large ships, all of which exceed in size even the largest of the liners of days gone by. Queen Mary 2, the flagship of the fleet, was the largest passenger ship ever built when she entered service in 2004 and cost £550 million to build."

Perhaps nothing underlines how times have changed more than the fact that QM2 is the only true transatlantic liner left in service.

Mr Frame said: "An ocean liner is different to a cruise ship in the way it is built to undertake deep ocean voyages such as Liverpool to New York. QM2 is built strong to withstand high seas on the Atlantic and is also the fastest passenger ship in service."

Ocean Queens: The History of Cunard and will be shown on BBC 1 in the North West on Friday 29 May at 20:00 BST.

- Published3 May 2015

- Published24 February 2015