How Kensington's Liverpool namesake fares badly in life

- Published

Victoria Road in Kensington, London, is starkly different to the tinned-up terraces of its Liverpool neighbour

They may share the same name, but the Kensingtons of Liverpool and London are separated by a lot more than 218 miles.

A boy born in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea - home to the most expensive street in England - can expect to live to the ripe old age of 83 - 13 years longer than one delivered in Kensington, Liverpool.

The life-expectancy gap has continued to widen since figures were first collated in 1991.

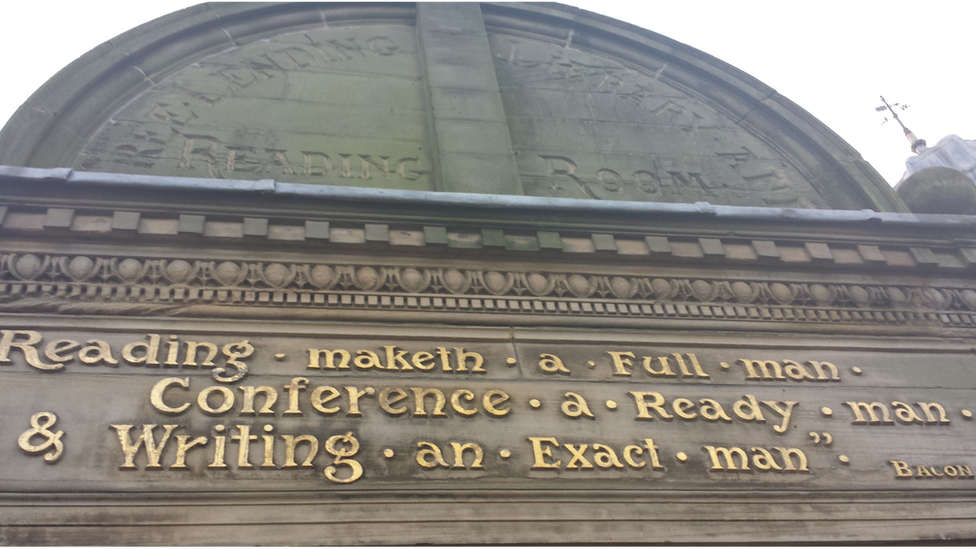

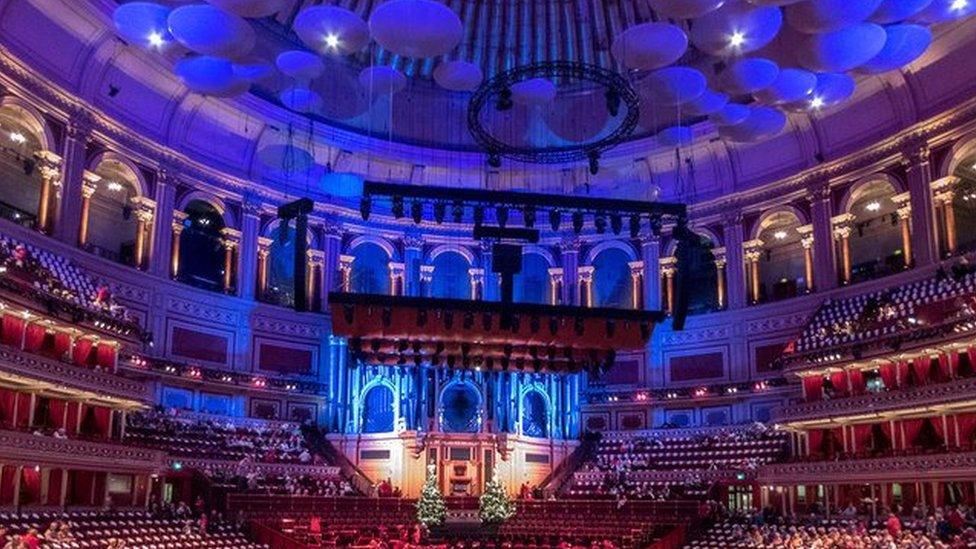

While the west London suburb of Kensington boasts the Royal Albert Hall and Kensington Palace, its northern inner-city namesake has the white-domed Kensington Picture Drome and a 19th Century library about to be taken over by volunteers following council cuts.

Nicknamed Kenny, it has a plethora of Victorian terraced houses and grander Georgian properties not too dissimilar to its southern namesake. Yet these homes do not command price tags of millions of pounds.

In Deane Road, the cockle pickers who died in the Morecambe Bay tragedy in February 2004 lived 10 to a room, while their neighbours were oblivious to their plight.

Actor David Morrissey was born in Kensington - the Merseyside version

Among the suburb's notable former residents are the actors David Morrissey and the McGann brothers, director Terence Davies and singer Natasha Hamilton of Atomic Kitten fame.

Lifelong resident Simon Huthwaite, who works with young people, said he knows some "who don't have a single family member in work".

He told the BBC: "For them, the Holy Grail is getting Disability Living Allowance. All the people they look up to are drug dealers who have nice cars and if you are young and in Kensington that can be your ideal."

Kensington v Kensington

Houses in Victoria Road, W8, cost more than £8m

In L6 and L7 some homes cost as little as £25,000 with Gothic-style villas costing £250,000

W8 has 12 of the 20 most expensive streets in England and Wales

According to the 2011 Census, the population of Kensington, London, is 64,681

Kensington in Liverpool has a population of nearly 16,000, according to Liverpool City Council

Unemployment in Kensington and Chelsea is 4.7% although 19% of those in work are paid below the London Living Wage

Paul McGann, who was also born in Liverpool's Kensington, played Doctor Who

So how can the yawning gap in life expectancy be explained?

Latest figures from indices of multiple deprivation, external show 98.2% of residents in Kensington, Liverpool - some 14,000 people - are in the most deprived 5% nationally - compared to a Liverpool average of 49.6%.

About four in 10 children live in low-income households - 1,295 are in poverty - which is more than double the national average. This has fallen from 49.5% a decade ago to 41%.

Average household incomes are £22,787 - £14,000 lower than the national average and just under £7,000 less than the city as a whole.

There are high levels of unemployment - more than 28% of working age men are jobless and 16.5% are claiming incapacity benefit. A third of the population aged 16 and over have no qualifications.

Crime levels top the city's average - 103 crimes per 1,000 people (91.1 is the Liverpool average) and 67.6 reports of anti-social behaviour per 1,000 population (51.2 is the Liverpool average).

Only a fifth of people are educated to degree level and only just over 1,000 residents are managers or professionals.

Local MP Luciana Berger is concerned about the gap between life expectancy in her constituency compared to London

In contrast, Kensington in London witnessed an influx of oligarchs and the super-rich and now has among the longest life expectancy in the world.

"Ultimately, this is also about wealth in the borough of Kensington, but there are also some inequalities within the borough, whereas Kensington in Liverpool has a lower base," a Public Health England spokesman said.

The latest life expectancy at birth figures for the Liverpool Kensington ward, which are from 2003, show on average males live to 70.4 years and females to 77.5, with an overall average of 73.8 years. This is almost 13 years lower than for their counterparts in the south born today.

Overall, Liverpool is 341st out of 346 local authorities for male life expectancy at birth and 338th for female life expectancy. A baby boy born in the city today would be expected to live to 76.

Kensington resident Simon Huthwaite said regeneration had made a "minimal" impact on his life.

A rebellious teenager, he has a criminal record, and said that he knows people stuck in the cycle of drugs that he was able to get out of. "If they work, they have low-paid jobs.

"For young people, if they have got money they graft and then go to jail and it's just part of life."

Kensington's library has intricate carvings with words picked out in gold lettering

Prof Mark Bellis, an academic who is an expert in public health and who has worked in the city for many years, said deprivation could impact on life expectancy - even from before birth.

He said there was a cycle of higher unemployment resulting in children having fewer life chances, the burden of health problems and poor housing.

"From early years onward, individuals in poverty have less resources to draw on, especially during times of difficulty, can have poorer access to professional and personal support and less opportunity and understanding about how to invest in their own long-term health," he said.

"In poorer areas things go wrong for everybody and they have less reserves - less money and family support."

It is difficult to chart why an area declines and another is regarded as up and coming. But he said it can become "self-fulfilling" once an area goes downhill. "People move out and you see a decline in property prices," he added.

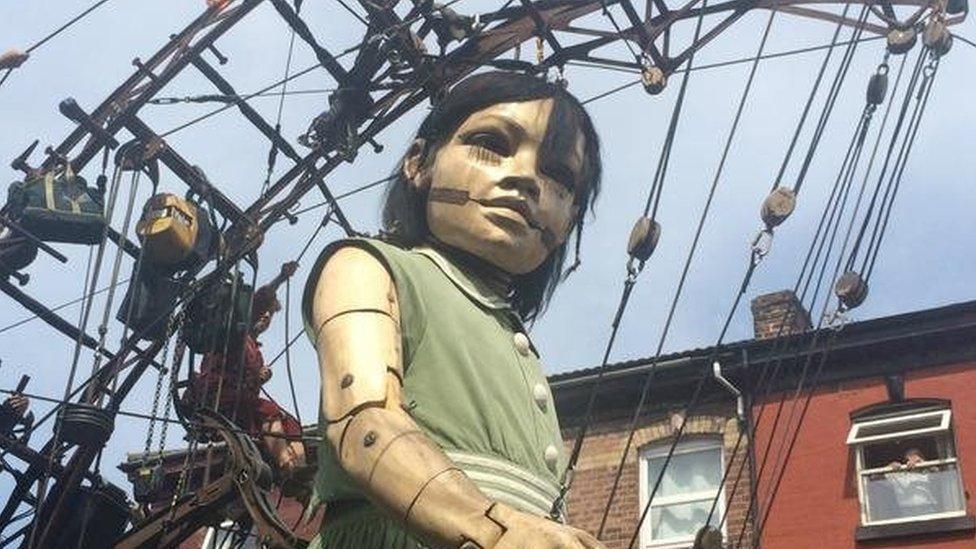

The Giants paraded through Kensington in July 2014

Kensington Picture Drome is a landmark in Liverpool

Luciana Berger, Labour MP for Liverpool Wavertree and shadow health minister, said: "It is appalling that in the 21st Century how long we live is still linked to where we live and how much we earn."

She said Liverpool faced "some of the toughest health inequalities in the country, yet this Tory government is inflicting some of the harshest cuts on our city, including to the public health budget".

Ms Berger called on the government to take urgent action to narrow the gap in life expectancy and "ensure that all children, regardless of where they grow up, have the same opportunities to lead healthy lives and fulfil their potential".

A Conservative spokesman said: "Contrary to the myth that Labour is keen on peddling, our long-term economic plan is actually delivering for the north of England.

"Employment is up, with almost three out of four jobs created since 2010 outside of London. There are also almost 119,400 more businesses in the north than in 2010 and nearly six million people in the region now have more money to take home each month as we have cut their income tax."

The Royal Albert Hall is one of the most well-known landmarks in the London version of Kensington

Councillor Wendy Simon, who has represented the area since 2006, said rogue landlords were an issue and the council had recently introduced a landlord licensing system that aims to combat the problem and improve conditions for tenants.

Sometimes, she said, residents got annoyed with the comparison with their wealthier southern neighbour. "They get fed up when they think it is being portrayed as all doom and gloom, when there are fantastic properties and beautiful streets. A lot of people are living quite positive lives."

The bandstand at Newsham Park in Kensington, Liverpool

In Kensington and Chelsea, the local council said it also had some social and economic challenges.

The commercial heart is Kensington High Street, and it houses many of Europe's embassies. It is famous for the Serpentine Gallery within Kensington Gardens and the Albert Memorial.

However, the area has faced competition from the opening of the Westfield shopping centre in Shepherds Bush, and it is the car theft capital of England and Wales.

Covent Garden in Liverpool city centre is also very different from its London namesake

It is also densely populated, with the high population partly a result of the subdivision of large mid-rise Georgian and Victorian terraces into flats.

A Kensington and Chelsea council spokesman said: "There's no doubt that many people enjoy a great quality of life in Kensington and Chelsea, and this has contributed to a longer average life expectancy in the borough.

"But that is far from the full picture. The council has a role to play alongside working with our local communities and our partners in health in helping to achieve better health for all our residents."

The council introduced public spaces protection orders earlier this month to crack down on supercars driven anti-socially.

Anyone breaching the order can be fined up to £1,000 for revving engines, racing, repeated sudden acceleration, performing stunts and sounding horns.

Tim Ahern, a councillor in the area, said he was aware residents "have suffered for some time with people racing around the streets, accelerating and braking and congregating on certain streets to show off their cars".

On the streets of Kensington in Liverpool, these problems seem like those taking place in another world.

- Published19 August 2015

- Published28 December 2013