Sir Henry Segrave: The legacy of the 200 mph record breaker

- Published

Sir Henry Segrave was the joint holder of the land speed and water speed record

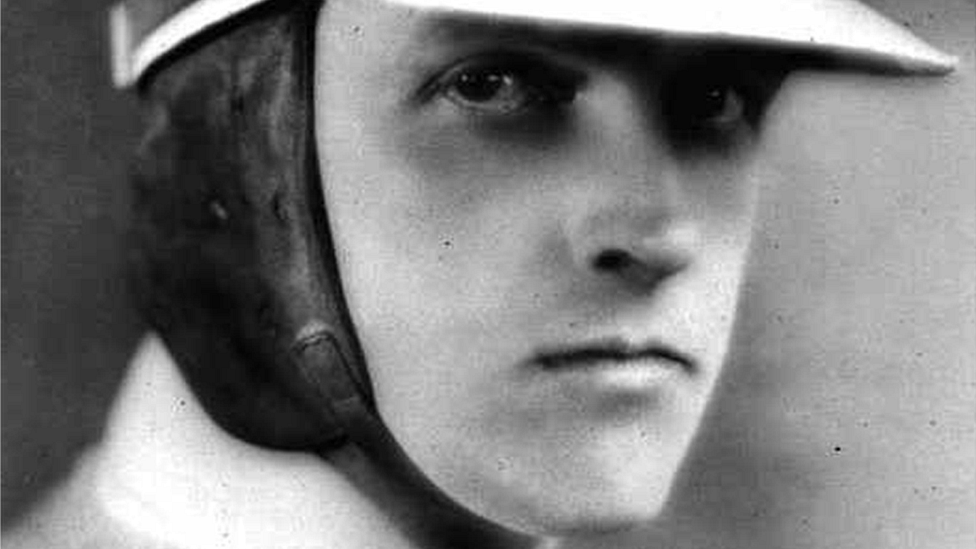

With his racing goggles and determined expression, Sir Henry Segrave epitomised a derring-do British hero from another age. But although he was the first racing driver to break the 200 mph barrier, he is not a household name. Why?

In the aftermath of World War One in the 1920s, when vehicles were becoming more reliable and crucially, faster, Sir Henry Segrave was at the top of his game. A star British driver.

Motor racing was in its infancy and many British roads were little more than dirt tracks littered with debris that threatened to scupper any record attempt, with disastrous consequences for both driver and car.

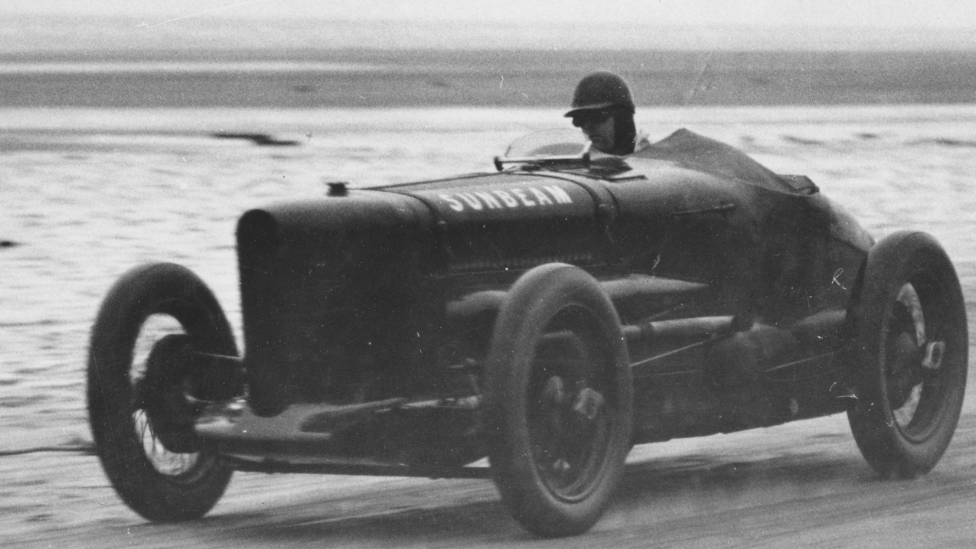

So on 16 March 1926, Sir Henry pulled on a pair of white overalls and took his four-litre British-made Sunbeam on to the sands of Ainsdale Beach in Southport.

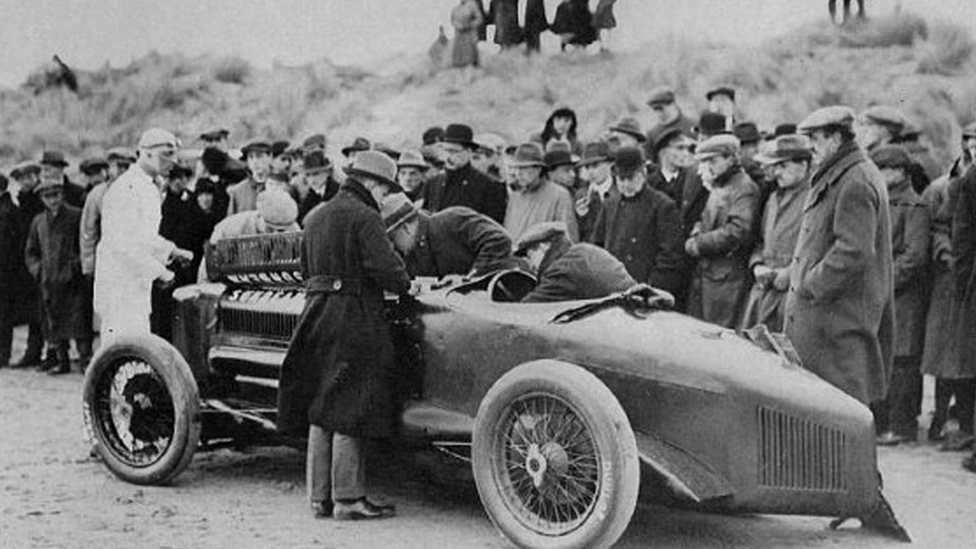

Watched by a large group of spectators, his car roared along the smooth, flat surface and reached a speed of more than 152 mph, seizing the world land speed record from his great rival, Malcolm Campbell (father of Donald Campbell).

His star was rising.

Sunbeam in action on Southport beach in the 1920s

Henry O'Neil de Hane Segrave was born in Baltimore in 1896 to an Irish father and American mother. A British national, he spent his childhood in Ireland and went to Eton.

He served as a fighter pilot in the Royal Flying Corps in World War One and became fascinated by racing cars once he left the forces through injury in 1919.

But although every flight during the war was potentially fatal, Sir Henry took a more measured approach to risk in his racing exploits.

The beach had been selected as the perfect venue for the record attempt as it was free of obstacles that could have lethal consequences - the slightest camber could have upended his car.

According to motor racing expert Ben Cussons, this was because at the time roads were in poor condition and there were "still horse-drawn vehicles being used". Many carriageways were "little more than dirt tracks with nails and other debris", he adds.

Sir Henry was unique in that he held both the land and water speed records at the same time, and tragically it was his pursuit of the latter that led to his death.

He sustained fatal injuries on Windermere at the age of 33, when he struck a log shortly after breaking the water speed record in 1930.

Sunbeam car driven by Sir Henry Segrave returns to Southport

His wife, Lady Doris, was determined to carry on his legacy and established an honour called The Segrave Trophy, awarded by the Royal Automobile Club (RAC) in his name to motor racing champions from 1930 onwards.

Previous recipients include Stirling Moss, Amy Johnson, Barry Sheene and Damon Hill.

Ben Cussons, who is on the trophy's committee, says Segrave was "multi-talented and very good at what he did", as well as being a self-made man.

Sir Henry was motivated by a desire "to be the best" at what he did, he says. "He earned his peers' respect because he funded his endeavours and found the funds and did not rely on family money."

"Segrave was not too bad an aviator, then he went into motor racing before land speed records, then water. He was always looking for the next new technology, which is what inspired him," he adds.

The fact a wider legacy eludes his name is more down to timing than talent, Mr Cussons believes.

He was simply not as well known as Malcolm Campbell because Campbell was Britain's first professional sportsman, backed by sponsorship (luxury watch brand Rolex) and with a strong identifiable brand in the Bluebird, says Mr Cussons.

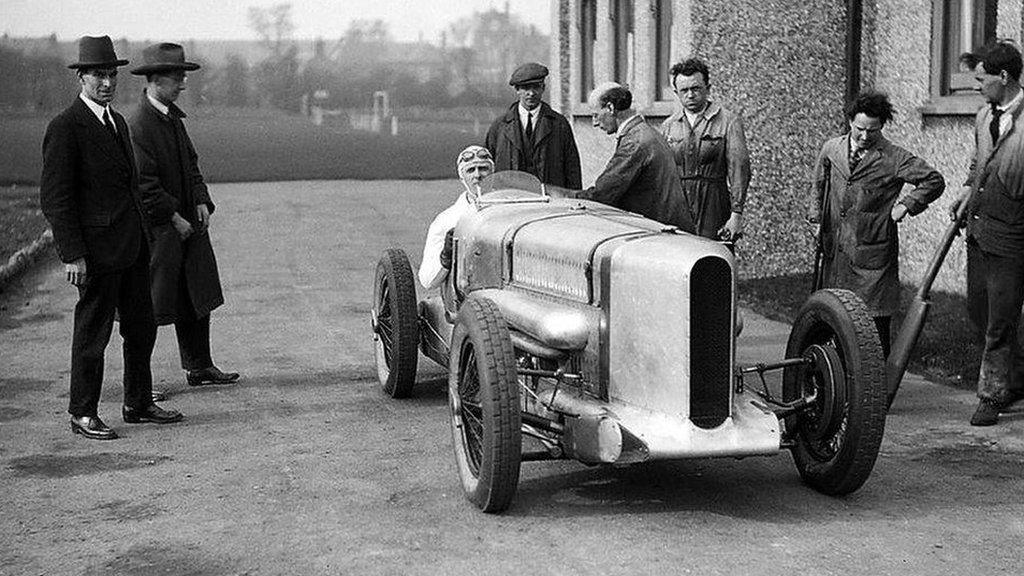

The Sunbeam on the sands at Southport before the record attempt

Nevertheless, Sir Henry - who was wounded twice in the war - was a "truly remarkable man" who achieved "an incredible amount in a relatively short life", according to historian and racing enthusiast Peter Cowley.

"He was a gifted racing driver and won many races, including five Grand Prix. Prior to Segrave's victory in the 1923 French Grand Prix, no British [team] had won a Grand Prix."

Sir Henry roared to success in a British car - Sunbeam. The next Briton to win in a British car was many years later, in 1955, when Tony Brooks raced to success.

More than 80 years have passed since his untimely death and now an independent documentary, called One Five Two at Ninety, is being made to bring his achievements to a wider audience.

What is known is that he had a fierce yet "gentleman-like" rivalry with Malcolm Campbell. Sir Henry liked to tell people he was the first man to travel more than 200 mph (320km/h) and he was clearly fascinated by speed.

Sir Henry's record was surpassed just over a month later by JC Parry-Thomas, in a car called Babs. Undeterred, Sir Henry snatched the record back in March 1927 in Daytona, taking the Sunbeam to 203mph - sealing his crown as the first man to exceed 200 mph.

The Sunbeam Tiger will be on Ainsdale Beach in Southport and is on display at the Atkinson gallery

Mr Cowley says that when Sir Henry died he was mourned by King George and Queen Mary, who described him as "one whose intrepid adventures on land and water were the admiration of the entire world".

Not only was he a speed king, he was a "highly accomplished" engineer who designed the Hillman Straight 8 Segrave Coupe and the Blackburn Segrave Meteor aircraft, Mr Cowley says.

Carol Spragg, editor of Historic Motor Racing News, says: "Sir Henry was a great pioneer of motoring and was a vast contributor to the progress of the motor car and the prestige of the British motoring heritage."

She believes the fact he died "so young" contributed to the fact he was not as well known as the Campbells, who had a very high profile and "playboy lifestyle".

"Segrave came from more of an engineering background and seemed to be more cerebral in his achievements," she adds.

The Segrave Trophy is awarded on merit and the next ceremony takes place in London later in March. It is a fitting tribute on the 90th anniversary of his land speed record achievement.

The Sunbeam was being driven down Ainsdale beach again on 16 March as part of a commemorative event to mark the anniversary of Sir Henry's record.

- Published16 March 2016