Penny Lane: Museum finds 'no evidence' of slavery link

- Published

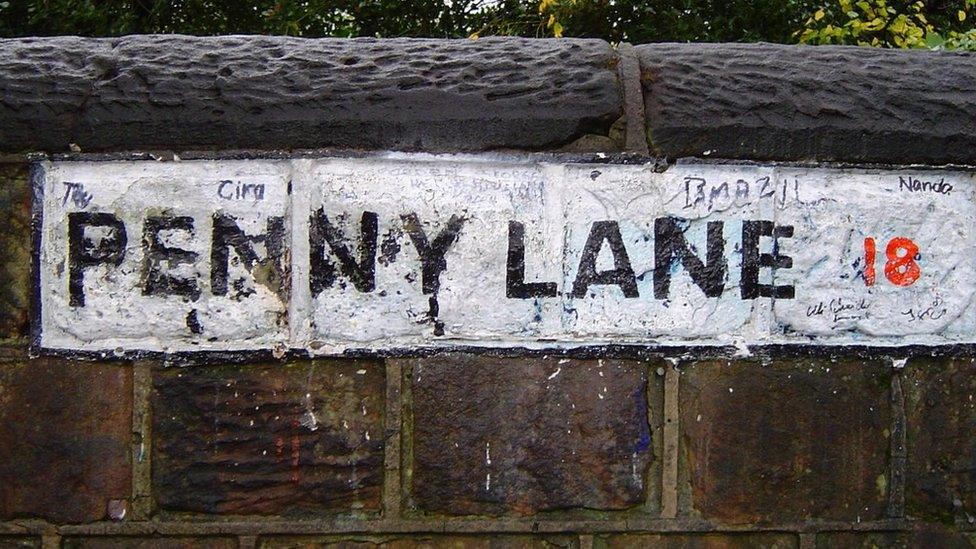

Penny Lane was immortalised in a song by The Beatles in 1967

There is "no historical evidence" to link Penny Lane to Liverpool slave merchant James Penny, the city's slavery museum has said.

The International Slavery Museum (ISM) included the street in a display when it opened in 2007, as the link to Penny "was in the wider public domain".

The truth of the link has been debated ever since and recently, belief in it led to street signs being defaced.

The ISM said "comprehensive research" had now shown there was no connection.

Janet Dugdale, National Museums Liverpool's executive director of museums and participation, said that after reviewing the display with historians and local schoolchildren, "we anticipate that our first action will be to replace the Penny Lane street sign with another".

Much of Liverpool's 18th Century wealth came from the slave trade and, by the 1740s, the city was Europe's most-used slave port.

Many of the city's streets have names linked to slavery, including Sir Thomas Street, named after the co-owner of one of the first slave ships to sail from Liverpool, and The Goree, which shares its name with an island off Senegal that was used as a base to trade for slaves.

'Mistake repeated'

In a statement, Ms Dugdale said there had been "much debate" about the origins of Penny Lane, which earned international fame in 1967 thanks to its use as a title for a Beatles song, but it was not clear how the name had originally come to be included in the display.

"We believe that the idea Penny Lane was named after... Penny was in the wider public domain during the time of the original Transatlantic Slavery Gallery, opened in 1994 within Merseyside Maritime Museum, well before the conception of the International Slavery Museum."

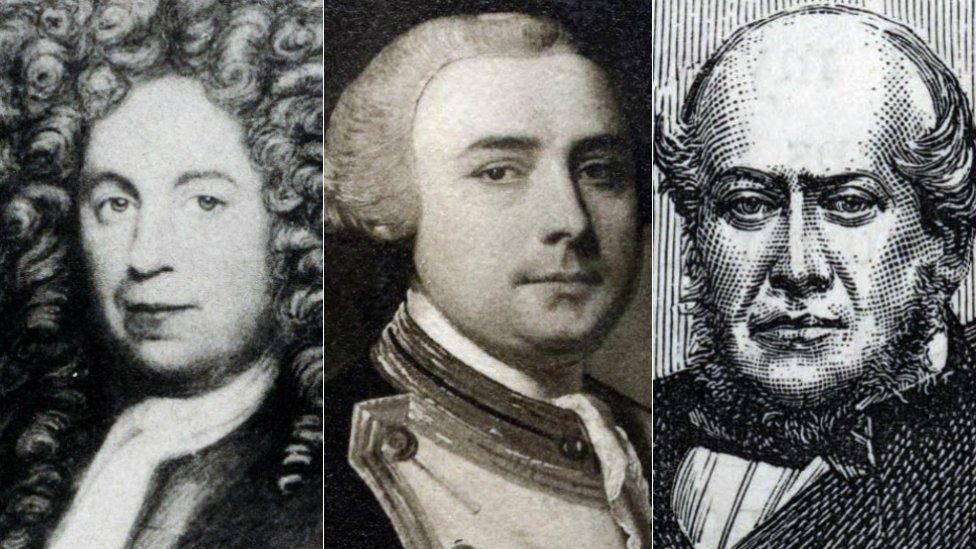

Who was James Penny?

Liverpool merchant James Penny captained 11 voyages carrying slaves and had his own shipping company, James Penny & Co

He was one of several Liverpool traders who spoke in favour of slavery at a parliamentary inquiry into the slave trade set up in 1788

In evidence, he claimed slaves on his ships were allowed to play games, dance and sing and would "sleep better than the gentlemen do on shore"

When Penny returned to Liverpool, the city's corporation, which was dominated by those with slaving interests, presented him with a silver-plated table centrepiece in gratitude

However, she said a review of the names included in the display, which had taken into account "new sources of information available to us since the museum opened", had concluded there was "no historical evidence linking Penny Lane to James Penny".

She added that "as an organisation which prides itself on learning and participation, we encourage debate around our collections to bring attention to the bigger issues in society".

"As historians and storytellers, we believe we have a duty as a museum to review, reflect on and respond to new information when it becomes available."

The possibility of a link led to street signs on Penny Lane being defaced

The chairman of the Association of Liverpool Tour Guides, Paul Beesley, said he had never seen any evidence linking it to James Penny.

"The road was named about 50 years after he died and although the origin is confused, none of the possibilities relate to James Penny.

"We believe that in 2007 when the museum opened, a mistake may have been made and that mistake has been repeated."

Historian Glen Huntley, who helped with the research, said he was "delighted" that the museum had "cooperated and responded to the research in such a positive manner".

- Published12 June 2020

- Published8 June 2020

- Published15 January 2020