Slave shackles put in Liverpool gallery to 'expose colonial links'

- Published

Ms Patterson said the decision to display the shackles was made "to show that slavery does not only exist in history"

A set of shackles that were used to imprison slaves have been permanently relocated to a major art gallery to "confront and expose the colonial links between slavery and art".

The irons, which were in Liverpool's International Slavery Museum, have been moved to the city's Walker Art Gallery.

They will be displayed with portraits of the slave-owning Sandbach family.

Assistant curator Alex Patterson said the restraints would help to tell the "uncomfortable truth" about the pieces.

A National Museums Liverpool (NML) spokeswoman said the move followed a project which had looked at how the Sandbachs' wealth influenced the city's "cultural, political and social development".

She said the family were part of a "dynasty" of "shipowners, merchants, bankers, politicians and plantation owners", who exported goods from the Caribbean and "became extremely wealthy through the enslavement, trafficking and forced labour of many tens of thousands".

The family were also awarded large claims in compensation after the abolition of slavery in 1833.

'Purposely omitted'

The shackles were used in what was called the "Middle Passage", the second section of the transatlantic slave trade.

The trade generally followed a three-part triangular route, with ships journeying from Europe to Africa to swap goods for people, before travelling on to the Americas, where those who survived the voyage were sold into enslavement and commodities such as sugar, cotton and tobacco were loaded for the return trip to Europe.

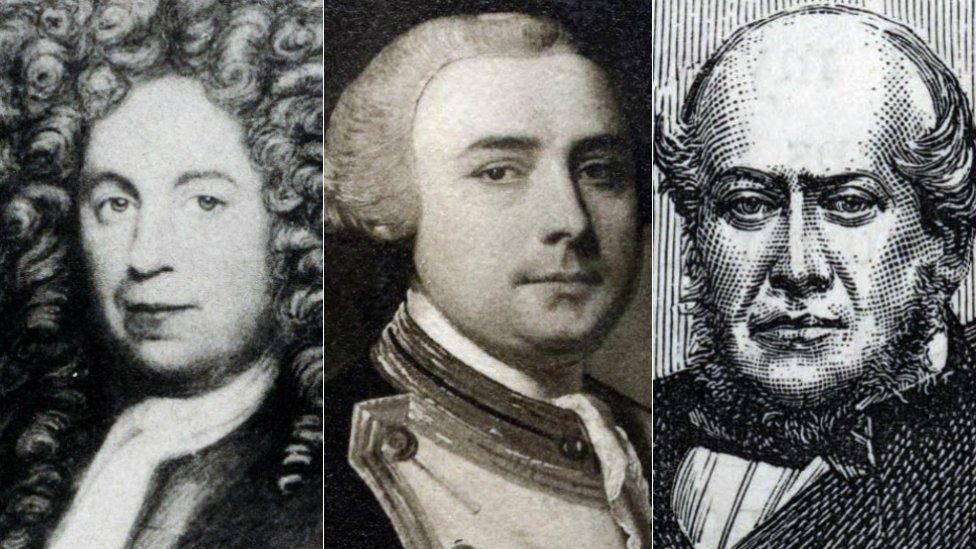

The Sandbach family appears in a number of portraits attributed to renowned 19th Century sculptor John Gibson

A steering group has led a project to "address the history and legacy of slavery" across NML's venues

The NML spokeswoman said the decision to display them beside the sculptural portraits was made "to show that slavery does not only exist in history... but that its legacies are still present in our streets, in our buildings and in our culture today".

Ms Patterson said it would help to tell "the uncomfortable truth about these objects".

"In the past, these histories have been overlooked, ignored, or purposely omitted from public view [and] this has meant we have only been telling one side of the story," she added.

The project was led by a steering group of "marginalised young people" and was part of the organisation's "ongoing work to address the history and legacy of slavery, empire and colonialism across its venues", NML said.

Steering group member Hatou Tangikora said the project presented "an opportunity to learn and educate yourself about black history, and the importance it had on the past, and the impact it still has on the present and future".

Liverpool and the slave trade

During the 18th Century, Liverpool made about £300,000 a year from the slave trade, which was about the same as the rest of Britain's slave trading ports combined

In the 1780s, Liverpool-based vessels alone carried more than 300,000 Africans into slavery and by 1795, the city controlled more than 60% of the British and more than 40 % of the European slave trade

Although Liverpool merchants engaged in many other trades and commodities, involvement in the slave trade occupied the whole port and by 1800, almost all its 78,000 citizens, including many of the mayors, were involved

Source: BBC Bitesize

Why not follow BBC North West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external? You can also send story ideas to northwest.newsonline@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published5 April 2022

- Published15 January 2020