People's March for Jobs: The protest that saw hundreds walk to London

- Published

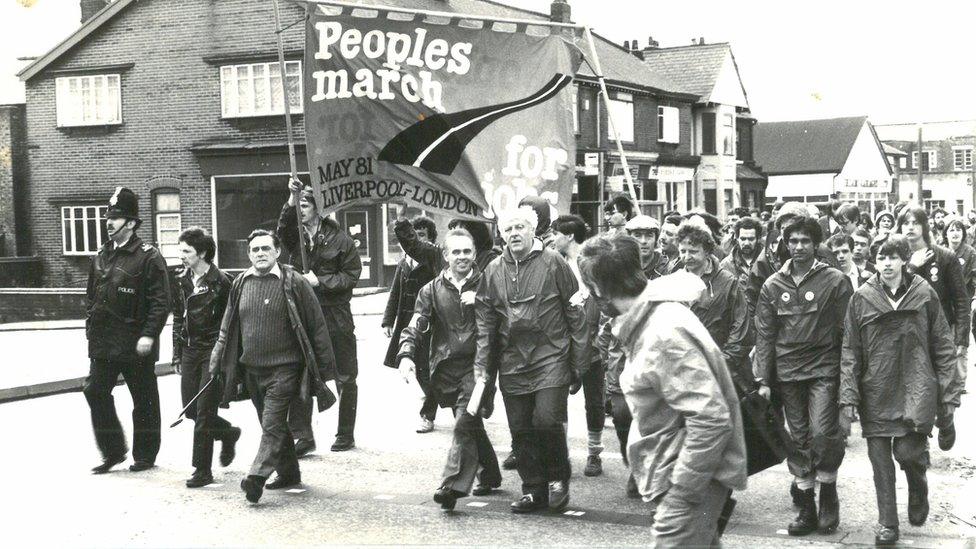

The month-long march weaved its way through England's industrial heartlands before arriving in London

In May 1981, 18-year-old John Williams set off on foot to London from Liverpool with a gang of mates and about 500 others to protest about unemployment.

Once the great port of the British Empire, Liverpool had lost almost 80,000 jobs since 1972 as the docks closed and its manufacturing sector shrank by 50%.

The city was not alone in its predicament.

More than 2.5 million people across the UK were out of work at the time and the marchers had had enough.

Mainly jobless people in their late teens and early 20s, they had attended a rally at the city's Pier Head, after which they began the People's March for Jobs, a long walk south to deliver their demand for jobs to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government.

As a new community project seeks to cast new light on what is now a largely-forgotten piece of Liverpool's history, John spoke about his involvement and how it changed him as a person.

"It was sold to me that there would be girls everywhere and loads of parties," he said.

"Two weeks in, I realised it was much bigger than parties and having a good time.

"When I came away from the march, I became a lot more political, there was a bigger picture."

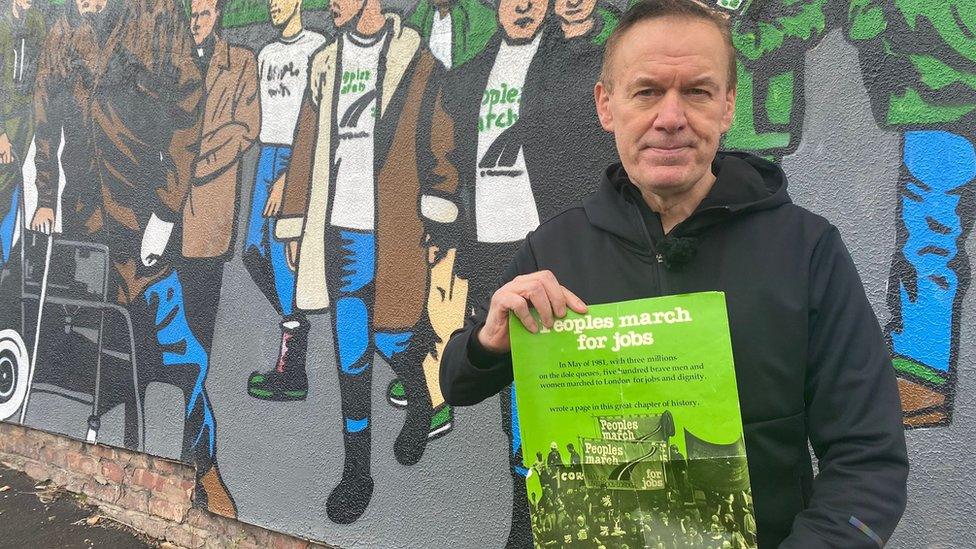

Keith Mullin (left, with George Allen and John Williams) said it was a "really important march that politicised so many"

Fellow marcher George Allen said he joined it because the decimation of manufacturing in his local community.

"Two weeks before, 2,000 people had been made redundant in Tate and Lyle's factory in Vauxhall," he said.

"A week before that, 600 people had been made redundant in Tillotsons.

"[That was] hundreds of people being made redundant half a mile away from where I lived."

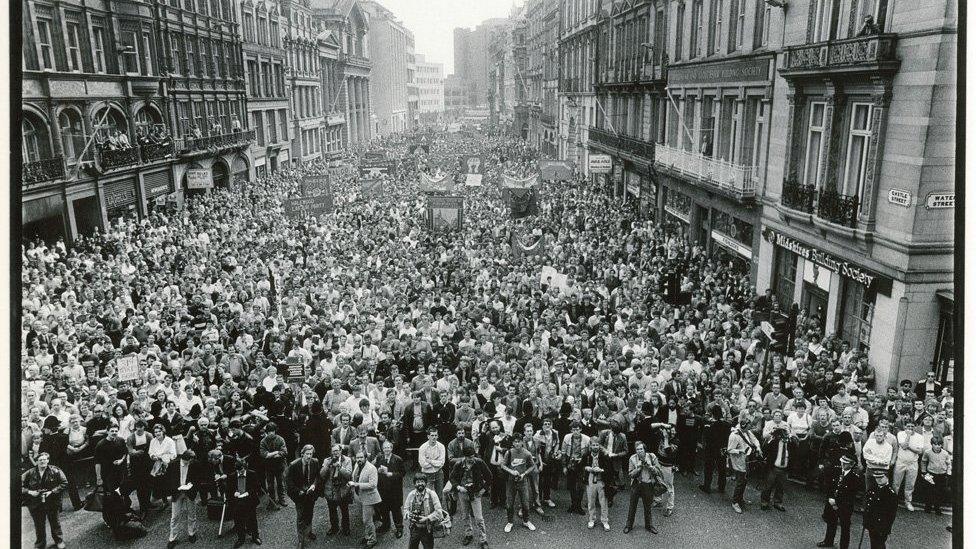

The month-long march weaved its way through the industrial heartlands of Stoke-on-Trent, Wolverhampton and Luton and arrived in London to a reception from the Greater London Council and its new leader Ken Livingstone.

There was also a Rock for Jobs concert, headlined by The Who's Pete Townshend and reggae stars Aswad, and more than 100,000 people joined a rally in Trafalgar Square.

The march passed through 22 towns and cities on its month-long route to London

George said the reception the marchers received "in the towns and cities was amazing".

"People embraced us and when we got to London, it was like a carnival - it was like a shot in the arm."

Keith Mullin, who would later find fame as a member of chart-toppers The Farm, was 19 when he joined his friends on the journey.

"I was part of that generation leaving school into what you considered a desolate climate," he said.

"[There was] not much in the way of jobs and all of your mates are unemployed."

"There were closures of factories all over the city."

The marchers were met in London by the new leader of the Greater London Council, Ken Livingstone

He added that it was not just his own predicament that spurred him on.

"My dad was a trade unionist and he'd been blacklisted and couldn't work," he said.

"That motivated me too."

Gary Rogers kept a scrapbook of newspaper clippings from the time and memorabilia, including a March for Jobs mug.

He said he "wasn't really into politics, but I wanted to make a stand, so me and my brother signed up and got marching with our boots on".

The hundreds who marched were of all ages, but most were unemployed

"It made me appreciate the hardship of what was going on across England," he said.

"We went to Hemel Hempstead and we walked past a factory where hundreds of people had been made redundant - and they came out to support us.

"I thought 'how good is that?'"

The project telling the story of the marchers takes its title from a phrase long associated with the era - Giz a Job.

It comes from Alan Bleasdale's landmark 1982 drama Boys from the Blackstuff and was uttered again and again by central character Yosser Hughes during his desperate search for employment.

The first part of the project is a mural on the end of a terraced street in Bootle, which features portraits of some of the marchers and their banners.

The mural is the first part of the Giz a Job project, which will tell the stories of the people who marched

Keith, who appeared on quite a few billboards while he was with The Farm, said it felt different to those pictures, adding that it was "where it deserves to be, on the side of a wall in a working class area".

"I am quite emotional seeing it," he said.

"The march has been lost in the mists of time, but it was a really important march that politicised so many people.

"I am immensely proud to be on it.

"I have a very different career now, but my heart still belongs there."

Gary Rogers collected newspaper cuttings and memorabilia from the march, including posters and a mug

Dr Greig Campbell, who is behind the project, said it was important because "unemployed people tend to be ignored by historians".

"They're often seen as marginalised people who are so focused on surviving that they don't actually engage in political activism," he said.

"That's not true.

"The march is an amazing case study where you can show that unemployed people aren't idle, they aren't unwilling, they haven't given up, they still fight for their own rights."

For John Williams though, the mural offers more than just memories.

"You wish you were 18 again, don't you?" he said.

"You don't realise you're 62 until you see things like that.

"I've said to a few lads in the pub, 'I'm on a mural in Breeze Hill'.

"I'm really proud to be on it."

Why not follow BBC North West on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external? You can also send story ideas to northwest.newsonline@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published8 November 2014

- Published9 April 2013

- Published9 April 2013