'For liberty and righteousness': A chaplain at war

- Published

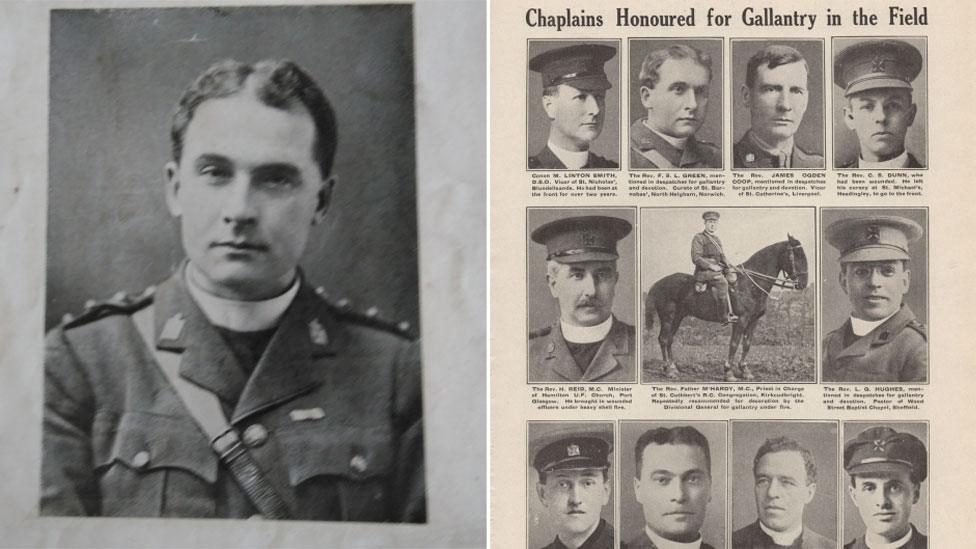

Between 300 and 400 Army chaplains were awarded the Military Cross during World War One - Samuel Leighton Green received the honour twice

Early on Christmas Day in 1916, a group of soldiers knelt on a rough floor in a candlelit barn in France to receive Holy Communion from their chaplain. The man tending to their spiritual needs was Samuel Leighton Green. He had swapped a quiet life as a Norwich curate to share in the physical and mental suffering of those on the World War One front line. Why?

Over the course of his time with the "blasphemous and foul-mouthed" 1/4th (City of London) Battalion (Royal Fusiliers), external, whom he had joined earlier that December and would remain with until war's end, Leighton Green lived in muddy, rat-filled trenches, under battle and bombardment.

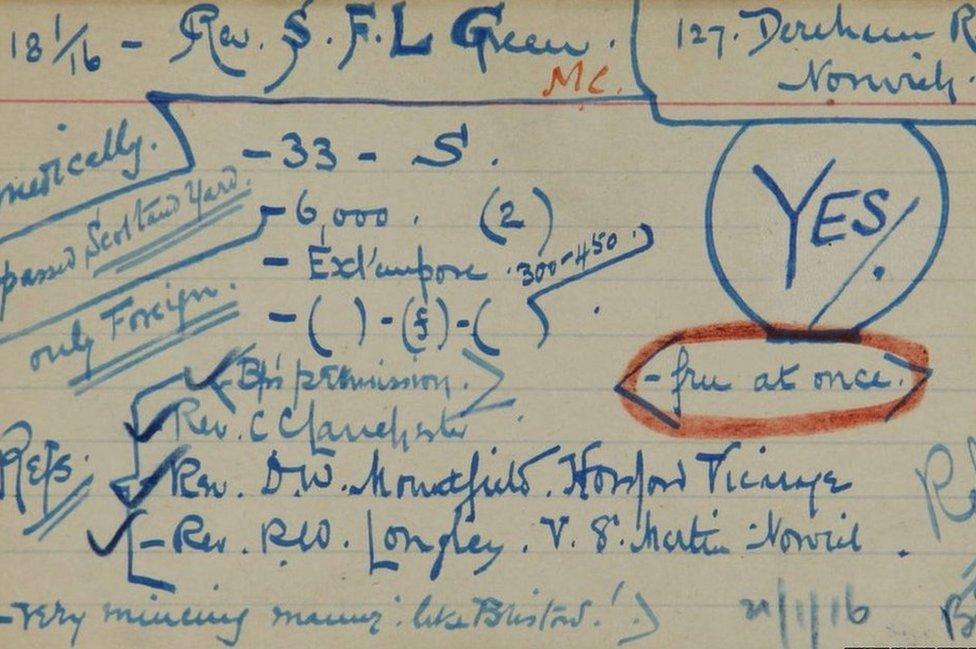

The chaplain - who had been derided by his interviewing officer Chaplain-General Bishop John Taylor for his "very mincing manner" - was gassed, injured, suffered trench fever and trench foot, and would be awarded two Military Crosses for his bravery.

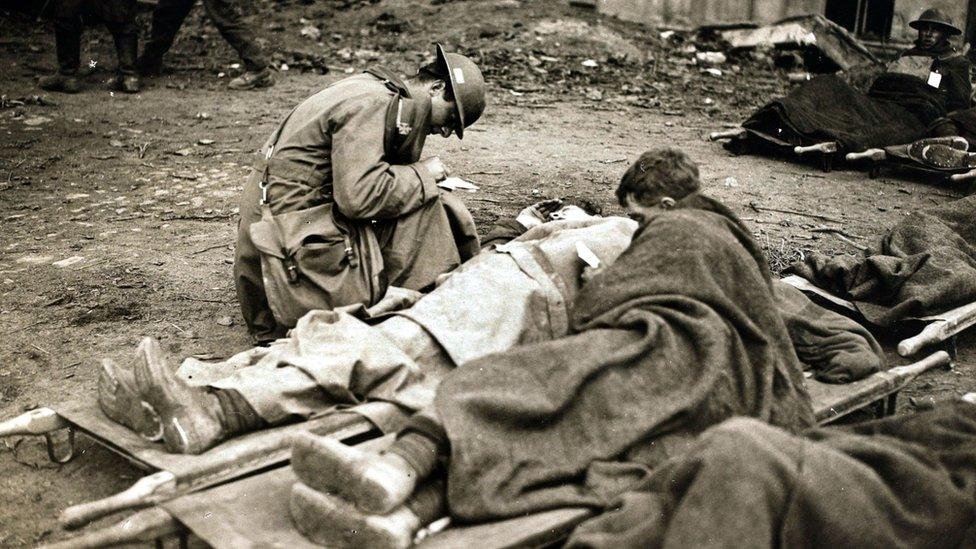

"When the men went over the top, he wasn't far behind with his first aid box - and then he would have to bury them," said his biographer Stuart McLaren.

The wretchedness and squalor of the battlefield at Arras were made worse by the snow, sleet and rain, Leighton Green wrote in May 1917

Leighton Green arrived in France in March 1916 aged 33, driven in part by a belief that the Allied cause was a just one. (He had volunteered - clergymen were exempt from conscription.)

He would begin documenting his experiences in missives sent back to his parish in Norwich. These monthly contributions to the St Barnabas Church newsletter left readers in no doubt about the "wretchedness and squalor" of the battle experience.

Rats "infest the trenches in huge numbers, so that as you walk along the trench at night you tread upon them," he wrote in March 1917.

"They run up and down the dug-out over your bed and everywhere."

On one particularly awful night he even woke "with a rat hanging on to my nose - I have never liked rats since".

On the padre's Army interview notes, Chaplain-General Bishop John Taylor scribbled a reference to Leighton Green's "very mincing manner"

On Easter Sunday 1917, Leighton Green was injured on the first day of the Battle of Arras as he watched "wave after wave of our men" go over the top.

"Presently the machine guns of the enemy began to open fire and one could see gaps here and there in the wave, but still they pressed on," he continued, later describing a mass burial.

According to Mr McLaren, the churchman volunteered because he believed in the "righteousness" of the British cause and felt a duty to bring Christian comfort to the troops.

He said: "Part of his job was to go through the horribly mutilated bodies, finding ID, and day after day he'd be burying these people, some days with 20, 30 or 40 burials."

He asked his Norwich parishioners to remember the men in the trenches, standing all night in the wet and cold, slush and mud

Leighton Green volunteered at a time when the chaplain's role was changing, following General (later Field Marshal) Douglas Haig's appointment as Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces in late 1915 and the introduction of conscription.

Michael Snape, the Michael Ramsey professor of Anglican studies at Durham University, said: "Haig understood the UK was a religious country and the clergy would have the moral authority to explain the causes of the war, which from the Battle of the Somme onwards they were progressively free to do."

This "recast the role of the military chaplain for the rest of the 20th Century and into the 21st Century", he said.

Prof Snape added: "The German, Austro-Hungarian or French chaplains were not expected to do what the British chaplains did, going round the trenches, talking to the men.

"Indeed, one of the many things chaplains made a point of doing was to speak to those on guard duty to help them keep awake, because to fall asleep was a capital offence.

"Britain didn't have the strong anti-clerical feeling experienced in Germany and France during the interwar period, and I believe this is in part because of what the chaplains did during World War One."

The chaplain's letters home described burying men on the battlefield, officers and their troops side by side in a long trench

And like so many of his contemporaries, Leighton Green believed the Allied cause was a just one.

"We are fighting for our homes, for liberty and righteousness in the world, for the safety and welfare of the generations yet unborn," he wrote in April 1918, after the London Fusiliers had endured "continuous and severe fighting" for several days over Easter.

"In such a cause we should all be willing to fight and suffer and if need be die."

Prof Snape said: "We've forgotten how contemporaries viewed the war, how righteous the cause was seen to be.

"By the 1960s, the play Oh! What a Lovely War was highly influenced by post-war myths and lies, and the parents of those who died were mostly dead themselves, so couldn't assert their sons didn't die in vain."

Life in the trenches demands incessant watchfulness, causing constant strain, the chaplain wrote in May 1918

Leighton Green also wished to bring the solace of faith to believers.

While the Army imposed a compulsory church parade on all Church of England soldiers, from which other denominations and faiths were exempt, chaplains could offer voluntary services, such as the ones Leighton Green held on Christmas Day 1916.

A typical Eucharist service attracted 70 or 80 men, while evensong was "usually overcrowded", he wrote home in July 1917.

He also held confirmation services for soldiers (to became full members of the Church of England). One such service in 1916 attracted 150 candidates, including "some fifty men direct from the trenches, covered in mud from head to foot and carrying the shell shrapnel-proof helmets".

Leighton Green suffered shrapnel wounds and was also gassed during the course of the war

And as well tending to his men's spiritual needs, the padre was also keen to cater for their practical ones.

He established a "Mag-Fag Fund", supplied by donations from his parish, urging those safely back at home in Norwich to send cigarettes - "they are always urgently needed".

"If only you could see the face of the recipients as I go round the ward with your cigarettes and magazines," he wrote on Palm Sunday 1916.

The Army did provide its troops with a weekly allowance - but 40 cigarettes a man would last "about 36 hours at most".

A parcel of 6,000 cigarettes, which arrived in May 1918, would "with strict economy last three days!" he wrote in May 1918.

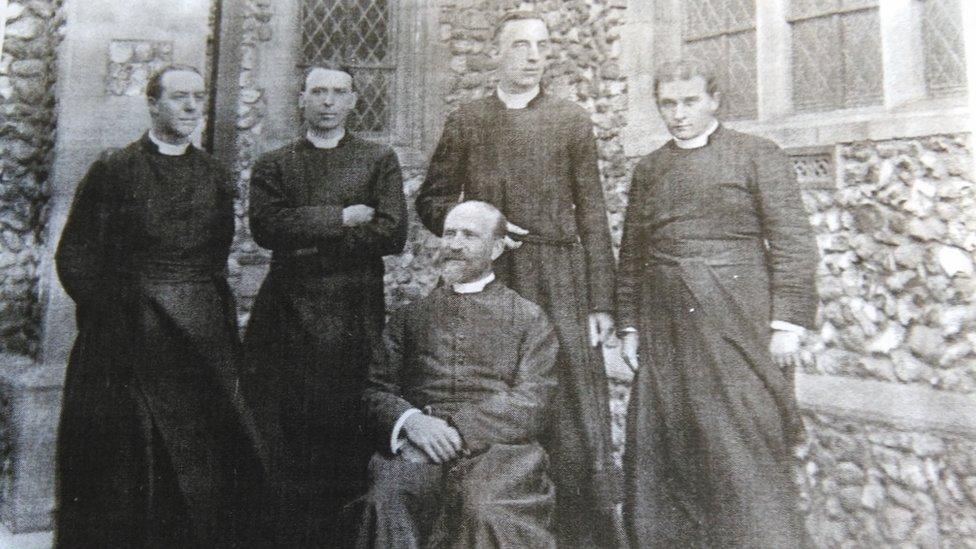

Samuel Leighton Green (far right) and his vicar the Rev Charles Lanchester (second left) at St Barnabas before the war. A year after his return he had a breakdown

Leighton Green would be awarded two Military Crosses during the course of the war, the second for staying "for over an hour with a badly wounded signaller lying out in the open under shell fire" at Sebourquiaux, on 4 November 1918.

When he was demobbed in 1919 the chaplain returned to St Barnabas, but in 1920-21 he had a breakdown.

"His legs were full of shrapnel when he was caught up in a bomb on Easter Day 1917 and he was gassed when he went through the Hindenburg Line in 1917-18, which prevented him from singing," said Mr McLaren.

"It would have broken a lesser man sooner."

Leighton Green recovered and became the vicar of the small fishing village of Mundesley on the Norfolk coast, where he maintained his connection with the men he had served by joining the British Legion.

He died aged 49 in 1929 and was buried with full military honours. An armed guard from the legion fired a volley over his grave.

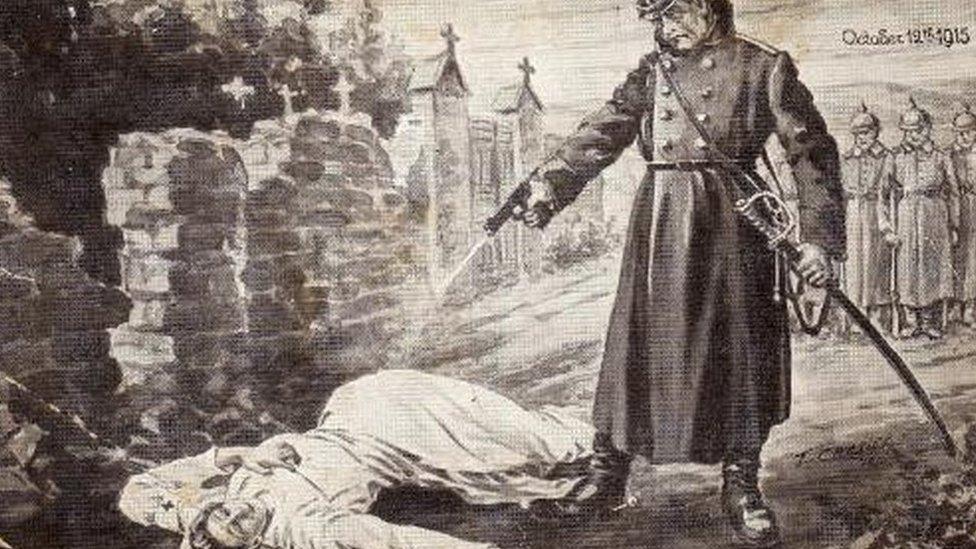

- Published12 October 2015

- Published14 November 2014

- Published10 November 2014

- Published29 August 2013