Miscarriage: 'I just felt like it was my fault'

- Published

An estimated one in four pregnancies ends in miscarriage - although there are no official statistics and the true figure could be lower or even higher. Many couples will never reveal they have had a miscarriage, but here, three women and one man describe the shock, guilt and distress they felt after losing their babies.

When Emily Daft described being left heartbroken by a miscarriage and her treatment by the hospital it prompted many other women to share their own experiences, external.

Mrs Daft started bleeding but was told she could not be seen by the hospital that day, and the miscarriage was only confirmed by a scan at a private IVF clinic. She later passed her baby "in agony" at home.

Many couples suffer "silent grief" after losing their babies, according to Ruth Bender Atik, national director of the Miscarriage Association, external.

"It's the loss of a baby however early in the pregnancy it was, and they sometimes carry that around with them, either because they are embarrassed or because they feel like they must have done something to cause it," she says.

Partly because of this silence, Ms Bender Atik believes many couples do not realise how likely miscarriage is.

"When you start learning about biology and pregnancy - you may learn for example about how not to get pregnant - there's not often much talked about what happens when pregnancies go wrong," she says.

"Few people know how common it is and most people are really shocked if it happens to them, really, really shocked."

However, people cope with miscarriage differently.

"For some people miscarriage is absolutely devastating, and for some people at the other extreme miscarriage is just a blip in their pregnancy history and they move on," says Ms Bender Atik.

"But it also has to be said there are some people for whom miscarriage might be a relief if this is a pregnancy they really didn't want and they were thinking of terminating."

Here, one woman describes the devastation of her first miscarriage, another explains how a miscarriage contributed to the breakdown of her marriage, and a couple explain how talking openly has helped them both.

'I thought it might come back alive'

Jackie Fretwell, from Ilkeston in Derbyshire, went on to have a daughter after having a miscarriage

"Some people say it's not really a baby if it's not fully grown but it is. It is still a child. It still had a heartbeat. It was still inside me growing."

Jackie Fretwell was 18 years old when she had her first of seven miscarriages in 1999.

When she became pregnant Jackie did not consider the possibility of losing her baby. Nobody talked about miscarriage back then, she says.

Even when she started bleeding from her vagina Jackie did not think she might be having a miscarriage. Even when she had a scan, and was told her baby had no heartbeat, Jackie refused the offer of surgery to remove it.

"Even though I was 10 weeks pregnant its heart had stopped at nine," she says.

"They offered to remove the baby. I think I actually thought it might come back alive and I said 'No, not yet'."

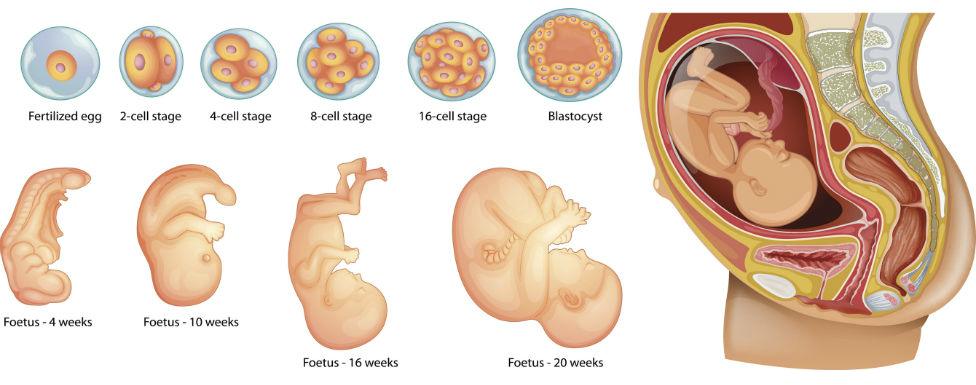

Miscarriage is the loss of a baby up to, but not including, 24 weeks of pregnancy. After this it is classed as a stillbirth

Jackie left the hospital and went home with her baby still inside her. It would have been her first child and she was utterly devastated to lose it.

"I had already chosen my pushchair and my Moses basket. I had gone overboard because I had never thought about miscarriage ever," she says.

"Your world falls apart right there and then. Things go through your head, like you are worthless, you can't do anything, you can't even carry children."

Jackie says she received no support from the health system because she was "just classed as miscarrying a foetus", but she found that talking to family and friends helped her get through it.

"It took a lot because I was a mess. I would cry and cry," she says. "You think that there might be something wrong with you as a person."

Jackie Fretwell now has three daughters and two sons

Jackie became pregnant again and had a daughter, now 17, and despite having a further six miscarriages she has given birth to a further four healthy children.

She now makes a conscious effort to talk more openly about miscarriage, and she no longer blames herself.

"I think you get stronger and you just want to be there for people because then some of my friends went through miscarriages," she says.

"I knew what they were feeling so I could relate to them and speak to them about it. And it helps, it helps to talk."

Miscarriage: The loss of about one in four pregnancies

Miscarriage is the loss of a pregnancy up to but not including 24 weeks of pregnancy. If the baby is lost after this point it is classed as a stillbirth

Unlike stillbirths, miscarriages do not have to be registered or recorded anywhere so there are no official statistics, but it is estimated that about one in four pregnancies ends in miscarriage

The majority of miscarriages happen within the first 12 weeks and by far the majority of those happen within the first eight weeks. When a woman gets to the second trimester - the middle three months of pregnancy - there is a much smaller likelihood of miscarriage

About half of miscarriages are thought to happen because something has gone wrong with the early development of the egg cell or sperm cell. Miscarriages can also happen because of a blood clotting problem which can starve the baby of oxygen, hormonal problems, a problem with the shape or strength of the uterus or cervix, large fibroids (non-cancerous growths) in the uterus, or infection

The main two risk factors for miscarriage are a woman's age and the number of miscarriages she has had before. As women age, their eggs too get older and there are more likely to be abnormalities

'I just felt like it was my fault'

Laura Bellamy, from Gedling in Nottinghamshire, said she "got on with things and cried privately"

Laura Bellamy says she still does not know how her ex-husband feels about the loss of their baby. They separated two years later, in March 2015, and she feels the miscarriage contributed to this.

"We didn't talk about it at all," she says. "It felt like I had done something wrong - I ate something, I lifted something heavy I shouldn't have. I just felt like it was my fault, that I lost our baby.

"I know he cried because he came home and did have a cry and then as he said he 'manned up and got on with stuff'."

The couple already had a son together, now aged 11, but had been trying for another child for at least two years.

"It just felt like I couldn't carry another child for him," Laura says. "It got to the point where I couldn't stand him in the room. I couldn't stand him touching me or anything.

"It was like a delayed reaction to what happened."

10 miscarriages in 10 years: One couple's heartbreak

Are men forgotten in miscarriage?

Losing a pregnancy in Iraq changed how I see miscarriage

Research has suggested that the standard of care for mothers experiencing the end of a pregnancy varies widely, external, and academics have called for a "standardised approach".

Laura feels her miscarriage was more distressing because of how she was treated by the hospital.

"I was stuck in A&E for eight hours while I was heavily bleeding and all they gave me was two paracetamols for the pain," she says.

Laura thought it was inappropriate for a heavily pregnant woman to scan her after her miscarriage

She was six to seven weeks pregnant at that point. The hospital did a test which indicated she was still pregnant, so she was sent home to rest.

"Two days after I went home I went to the toilet and that's when I miscarried because it landed in the toilet and like the silly girl that I was I scooped it up and put it in a box," she says.

"My friend took me back to the hospital and they said it was a blood clot, but I knew in my mind that was my baby."

She returned to the hospital again the following day for a scan, but the woman who called her name was heavily pregnant.

"I didn't think that was right at all," she says. "I stood there and said I wanted somebody else to scan me, and they got somebody else to scan me, and that's when they told me I had miscarried."

Before her miscarriage, Laura did not know how common they are.

"I would have been able to talk to people if I'd known what other people had gone through," she says.

"I felt very sad, I had a couple of weeks off work. I had a son to look after so I just put it in the back of my mind and got on with things and cried privately.

"I didn't go to any support groups or anything, I just carried on."

'This is a possibility, not a pregnancy'

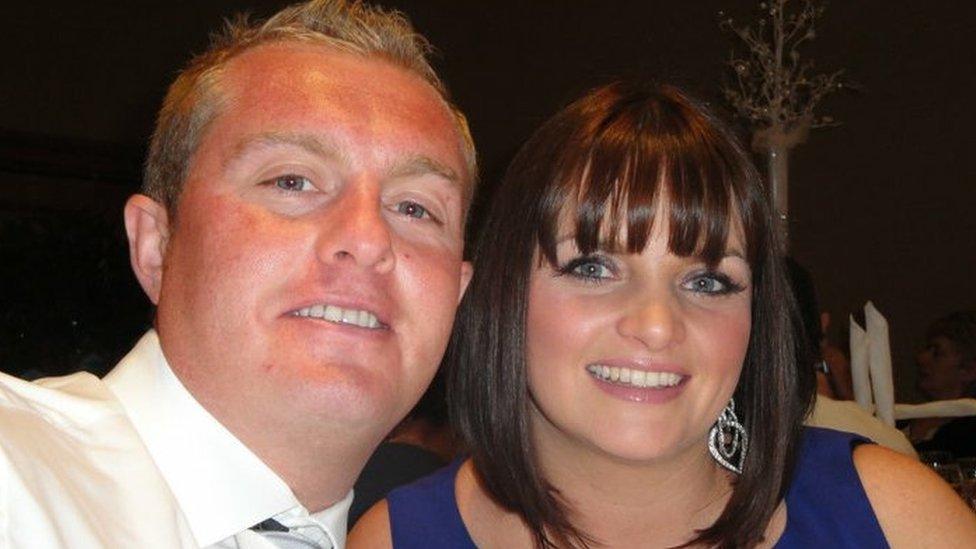

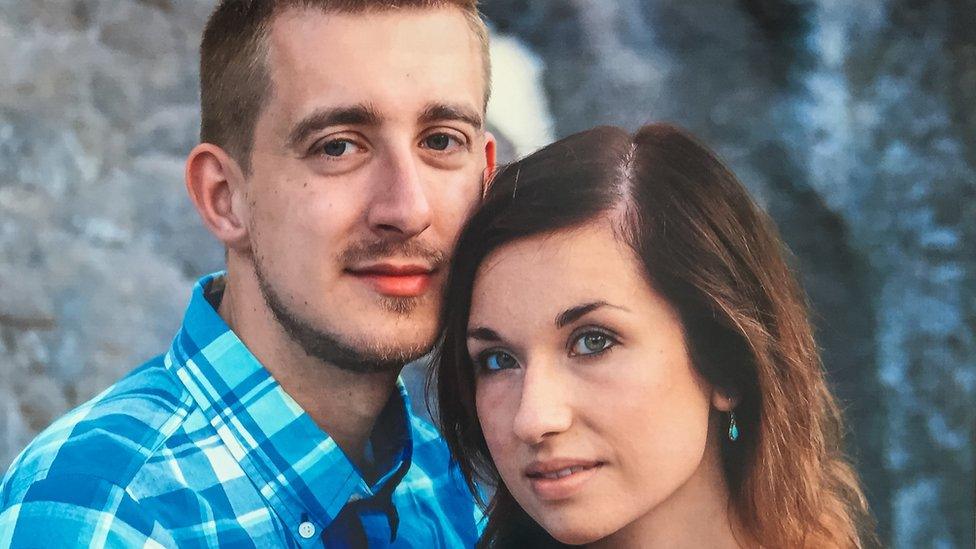

Alice and Phill Johnson, from Clifton in Nottingham, have a two-year-old daughter together

Phill Johnson should have been celebrating his birthday when his wife Alice was lying in a hospital bed, having lost their baby and almost bled to death.

He found the experience in December so "horrific" he does not want Alice to tell him if she becomes pregnant again.

"Personally it kind of tore me apart inside but you can't show your missus that because you've got to be strong for her."

"I don't want to know until she's at least four months," says Phill. "I don't want to get excited about having a new baby and then something like that happens. I can't deal with that again."

Alice's experience was particularly difficult because she had to make her own way to hospital by tram, after being told she could not get an ambulance.

"The tram was covered in blood," says Alice. "I had got members of the public trying to keep their eyes down trying to avert their attention.

"It was incredibly embarrassing. The pain was nothing in comparison. It felt like my dignity had been torn away from me.

"It was the blood and where it was coming from. It's just undignified. Childbirth isn't the most dignified thing in the world, but I wasn't having a child, I was losing one."

Alice Johnson had a very public miscarriage - on a tram in Nottingham

Alice had lost five pints of blood by the time she got to hospital, due to a tear in her womb, but despite the huge physical trauma she has coped surprisingly well emotionally.

She attributes this to already having known about the risk of miscarriage.

"My sister has been through miscarriage a few times," she says.

"So as soon as I had that little bit of bleeding I knew there was something going wrong. Then when it completely burst I knew that was it. There was no chance that a child was surviving that."

She believes miscarriage would be "less devastating" for younger women in particular if they were aware of how common it is.

"They would be less anxious about their pregnancy knowing that you've got to think of it as 'this is a possibility, not a pregnancy'," she says.

Phill does not want his wife Alice to tell him if she becomes pregnant again

Phill has talked to "maybe one friend" about the miscarriage.

"Men should be able to talk about these sort of things but society has kind of groomed you not to," he says.

"I've seen young men where the loss of a child has made them lose the plot. It sends them mad upstairs, they become disconnected from friends, from family, from their girlfriend, wife.

"Men shut down and it's not a good thing for a man to shut down because it's very difficult for a man to open up again.

"A loss of a child is obviously a horrible thing to feel, but men don't talk about this sort of thing and it drives you crazy in your head, simply because you have to be tough, you can't show emotion."

He also believes it's crucial for couples to support each other through it.

"Families break up because of this and it shouldn't be like that at all," he says.

"She becomes depressed because the closest person to her would have been her husband and he probably doesn't talk. He probably shut down, switched off, didn't want to talk about it because it's too painful. But you can't do that.

"You have to talk about these things, no matter how much it hurts. Cry on each other's shoulders. Hug each other until you fall asleep. Both of you have got to remain and stick with each other and keep that close bond with one another, otherwise you will drift apart."

- Published2 February 2018

- Published5 January 2018

- Published11 October 2017

- Published25 June 2017