Beechwood: 'I can't believe the evil that happened there'

- Published

Survivors of the regime at Beechwood have described an environment in which sexual abuse was rife

For decades, young people at a Nottinghamshire children's home were subjected to a regime of sexual and physical abuse. Boys and girls were watched while washing, groomed and assaulted in their beds.

Laura was one of those children. One of the witnesses at the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA), external, she has been speaking to the BBC about her time at the notorious Beechwood Community Home.

This article contains details of child abuse some readers will find upsetting

Laura came home from school one day to find her suitcases packed and a social worker waiting for her.

Feeling "totally abandoned" and "absolutely heartbroken", she was taken into Enderleigh, one of the four units comprising the Beechwood children's home in Mapperley, just outside Nottingham city centre.

Even though she was only there for a matter of weeks, Laura - not her real name - became one of the many residents who were sexually abused.

Now in her 50s, she is telling her story in the hope it helps other victims of abuse in the care system, and highlights their fight for justice.

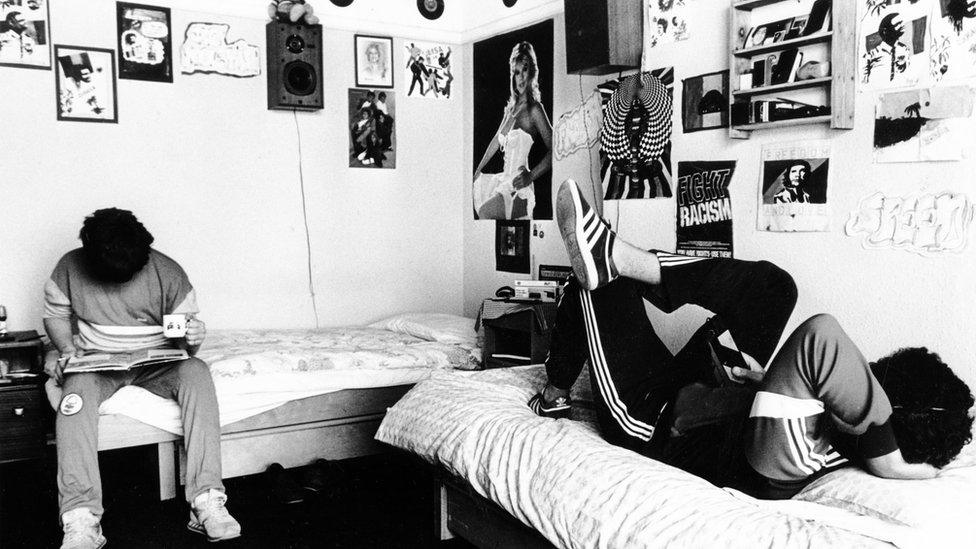

Former Beechwood residents told the inquiry of run-down conditions in the children's home

Laura, who grew up in Nottinghamshire feeling "unloved" by her family, vividly remembers arriving at Beechwood shortly before her 15th birthday.

"I was taken by a social worker, and from the outside I thought it looked like a lovely house," she said. "It was a big place, it had like a balustrade balcony that ran around the upstairs - it looked so pretty, almost a little colonial, with trees and flowers outside.

"As soon as you went in, the atmosphere changed. It was a horrible place. The doors that would have opened to the balustrade were all boarded, the beds were just metal and horrible, there was nothing in there that was soft or homely.

"It was almost like an army barracks - just bare walls."

Laura said she initially thought Beechwood's Enderleigh block "looked like a lovely house"

Beechwood first opened in November 1967, and by 1976 it incorporated four units, with an administration building augmented by the Enderleigh, Lindens and Redcot sections.

Its original reputation as a home for criminal children endured - as did Enderleigh's notorious padded cell - and reports from staff repeatedly referred to the "appalling and squalid" state of the buildings. The state of them was so bad, it led to one visiting psychologist asking: "How is it we can place young people in such atrocious conditions?"

If you are affected by any of the issues in this article, click here for advice.

The standard of "care" on offer at Beechwood was similarly appalling: children were dragged by their hair across rooms, stripped naked to stop them leaving and made to fight each other.

One resident said he was forced into masturbation competitions by staff, while another said she was visited and raped at the home by the same man who had abused her before she was taken into care. Some also described being raped by staff - and being punished for speaking out about the abuse.

When Beechwood closed for good nearly 40 years later, hundreds of children had passed through its doors, with many left permanently damaged.

Children at Beechwood - seen here in a 1981 BBC documentary - said violence was a regular part of life at the home

The daily routine was dull, Laura said, with residents largely left to their own devices.

"Even though there was school, there was no education going on there," she said. "After school you'd get frogmarched back down the road - you'd only do half a day, because you'd get back for lunch at 'home'.

"Lunch was in a big room; we'd just sit there and have whatever was put in front of us, which was never very appetising, just your usual stodgy, plain stuff. After lunch you then just found something to do.

"I tried to do a bit of calligraphy, just for something to do, because there was nothing in the activity room, there was nothing really there. A record player with about a dozen singles, a table tennis thing, but that was basically it in the whole place. Horrible.

"It was dead old-fashioned - we had those cast-iron baths which were either freezing or boiling, and there were no doors on the bathrooms, so anyone walking by could see whatever you were doing in there.

"It seems strange, but it even smelled old; just damp and fusty."

Laura said her early encounters with John Dent, a resident social worker, were initially positive, which she now knows was part of the grooming process. The first time Dent sexually assaulted her was the day of the FA Cup final.

"He told me if I wanted to ring my boyfriend, I could use the phone in the office, and he went and he bought some stout and cigarettes and, you know, I was allowed to have a drink, and he was being very friendly," she said.

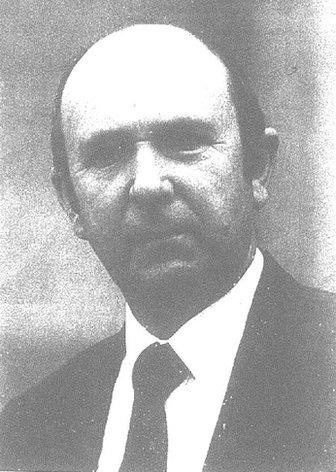

John Dent was convicted in 2001 of sex offences involving several children

"That same evening he came up to the dormitory in the middle of the night, and this was the first occasion that I woke up with him on top of me. He got his mouth over my mouth, and he says, 'I'm not going to hurt you. Please be quiet, I'm not going to hurt you.'

"I was just rigid… I said 'no', and when I realised I could feel his erect penis rubbing against me, I was really, really scared."

Laura said she "couldn't believe what had happened" with Dent, but did not know how to report it.

"I had nobody to tell, I had nobody to talk to. I just felt that people would just think I was a rebellious teenager and making excuses, that I was in a care home and I wanted to get out."

Away from her family, Laura was in a very vulnerable position - one that Dent readily exploited. After her roommate was moved, she was on her own every night. "At every available opportunity he was coming again into the dormitory," Laura said during the inquiry.

Despite fighting off Dent during the abuse, Laura feared challenging his authority and reporting what he was doing in case he kept her at Beechwood. "He always used to say: 'It's my say-so whether you go home at the end of this term.' He made that really, really clear on lots of occasions."

The inquiry heard how Beechwood staff members targeted children in their care

Laura left Beechwood weeks later, but the scars of her short stay have endured.

She took an overdose soon after leaving the home, and felt "awful" for years after. After two decades of keeping the abuse secret, when her daughter reached the same age she had been when admitted to Beechwood, it became too much to bear.

"I had the chat with my daughter, and I tried to explain everything that happened in a balanced kind of way," Laura said. "I thought I had done quite a good job with it, I thought I was so grown-up and could handle it, but when I explained to her that past, seeing her come down the stairs brought it all back - it made me feel like I had to do something about it.

"It had such an adverse effect on her - she felt that if she hadn't been born then she wouldn't have reminded me of that awful time."

Years later, Laura learned how her daughter drew inspiration from how she handled her ordeal.

"I found out there was an essay thing she had to do in school," she said. "People were writing about who they admired, so they talked about celebrities - Princess Diana, people like that - and she wrote about me. She wrote all about what I had been through, and she said she was really proud of me.

"She wanted to be there to support me every step of the way in court - to the point that Dent clocked her one time, and he looked quite taken aback because she looked quite like me when I was that age.

"It was only in the last five years or something like that [that I found out about the essay]. It made me cry."

Beechwood was eventually closed in 2006

Laura said she was treated sympathetically by the police when she came forward, and eventually an investigation was launched into Dent's activities.

A trial followed, but in a case that was in essence Laura's word against Dent's, he was acquitted of the charges relating to her - a common experience for those alleging abuse against figures of authority. However, after she came forward to report his abuse - the first person to do so - others did too, and at a second trial he was convicted of child sex crimes, including those committed at Beechwood.

Dent received a prison sentence of seven years, although for Laura he "got away very lightly". Nearly two decades after he was jailed, she said she still suffered from the ordeal of the court case.

"I'm still in fear. It's a real fear to me that he will one day blow up at me, because if it wasn't for me he wouldn't have been in prison, and now it's all kicked off again [with the inquiry]."

IICSA: A story of national neglect

Announced in 2014 by then Home Secretary Theresa May, the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse followed years of abuse cases coming to light.

The care system in Nottingham and Nottinghamshire is one of 14 investigations to be conducted by the panel, with 343 people getting in touch to describe abuse in the care system there dating back to the 1960s.

Over 15 days of hearings in Nottingham and London, evidence from 115 witnesses was heard, with 2,299 documents totalling 39,464 pages disclosed to the inquiry's core participants.

Of those 343 people - a number that Nottinghamshire Police admits represents "the small tip of a very large iceberg" - 136 allege abuse at Beechwood, and the home is a central part of one of three strands of the IICSA's investigations into the care system in the county, the others focusing on abuse in foster care and child-on-child sexual abuse.

The inquiry has been looking at children's homes and foster care in Nottingham and Nottinghamshire

Former foster care and children's home residents who submitted statements and gave verbal evidence related a string of harrowing experiences to the inquiry. Many also spoke about the lasting effects of the abuse - of addiction problems, mental trauma and a lack of trust in the authorities.

As well as Beechwood, children's homes across Nottingham and Nottinghamshire's care system were also mentioned, with the likes of Amberdale, Bracken House, Greencroft, Skegby Hall and Wollaton House all listed as locations where abuse took place.

Myriam Bamkin, Dean Gathercole and Barrie Pick are among those to have been sentenced for crimes committed at Beechwood and other Nottinghamshire institutions. In 2016, when Andris Logins was jailed for 20 years for offences stemming from his time working at Beechwood, the judge was damning, describing it as "a home from hell".

A crucial support system for Laura has been the Nottingham Child Sexual Abuse Survivors Group. With its help she found the strength to talk to other victims, and she was the first person to give oral evidence to the IICSA's Nottinghamshire investigation.

"It's been an absolute lifeline for me," she said. "To be with people that have been in and around the same group of homes in Nottinghamshire - you can learn from each other. People talk candidly about what's happened to them, how they cope or how it affected their families.

"The fact that there's so many of us makes you feel like you're not going round the twist, and when I hear about what happened to some of the other ones I feel I got away very, very luckily."

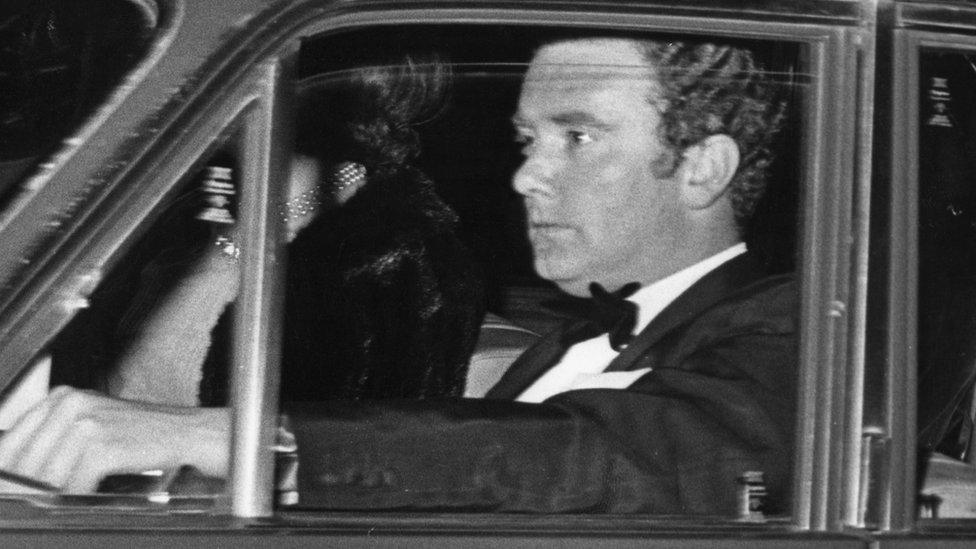

Prof Alexis Jay was named chair of the inquiry panel in 2016 - the fourth person to hold the post

The evidence sessions for the Nottinghamshire element of the inquiry have ended, and the IICSA panel will now write a report on the care system's failings.

With tens of thousands of pages documenting decades of abuse at Beechwood, the report is not expected until later in the summer. The wider inquiry is set to run until at least 2020. Despite this, before the inquiry had heard any evidence, the flood of apologies had begun.

Nottinghamshire County Council made its mea culpa in January 2018, with Colin Pettigrew, its director of children's services, later telling the inquiry he had "sobbed in the aisles of Asda" when talking to his wife about one of the abuse survivors.

Nottingham City Council, which the inquiry heard had discussed apologising "when there is something to apologise for" at a meeting last year, offered some words of contrition two weeks before the hearings opened., external During the inquiry, its then portfolio holder for children's services David Mellen - now city council leader - repeated the council's words of regret, adding: "We should have apologised earlier."

For many, though, these apologies were not enough.

Laura, who was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in 2004, said: "My education was ruined, and I've spent the whole of my life suffering with depression.

"I see myself back in the room. I can just see it so clearly, the room with the metal bed frames and the bars on the windows. And it happens when I have had a reminder - a song on the radio, or a film that was popular at the time. The FA Cup final every year does for me."

Feeling angry that the abuse she and so many others were subjected to could have been stopped earlier had children been listened to, Laura - like other survivors - has called for mandatory training for police in dealing with abuse victims, and for an independent body to deal with social services records to ensure they are not destroyed.

She has also called for accountability at the councils responsible for Beechwood and all the other children's homes and foster families where abuse took place.

"It's such an enormous scale of abuse," Laura said.

"I can't believe the evil that happened in those places. I really can't."

- Published24 November 2018

- Published4 March 2019

- Published13 February 2019

- Published12 April 2018