'I grew up in a Victorian workhouse'

- Published

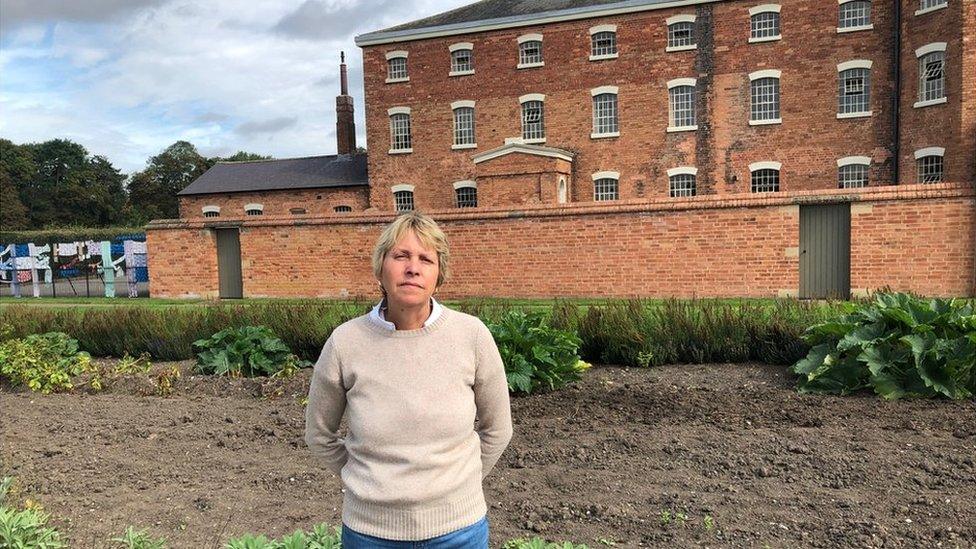

"It was so lonely," says Susan Swinton of her childhood

The harsh regime of workhouses is something we associate with Victorian times. But the shocking truth about the buildings is that they continued to house families well into the 20th Century. BBC News Online speaks to a woman who grew up in one.

At the age of eight, Susan Swinton was shown into a room, together with her mother Joan, 10-year-old sister and brothers aged six and one.

The room was narrow - only about 18ft (5.5m) wide - and stark. Cream paint flaked from the walls. Five iron beds with thin sheets, evenly spaced, were set down one side of the room. There was not much other furniture - a table, a cooker, a small sink and a coal bucket.

"I would stand for hours, just looking out of the window," says Susan

At the far end were two barred windows. There were no curtains.

If you tried to look out at the world beyond, your view was blocked by a high line of hedges.

A fierce Scottish matron ran the children through a list of rules, most of which started with the words: "You must not". They were told they must never go into the orchard at the other side of the building. They must never hang their washing outside. They must never venture through the velvet-lined door - beyond it was the staff quarters.

If they were caught transgressing, the family was told they would be thrown back out on to the streets. The room, the dark passage outside and a small courtyard were to be their domain.

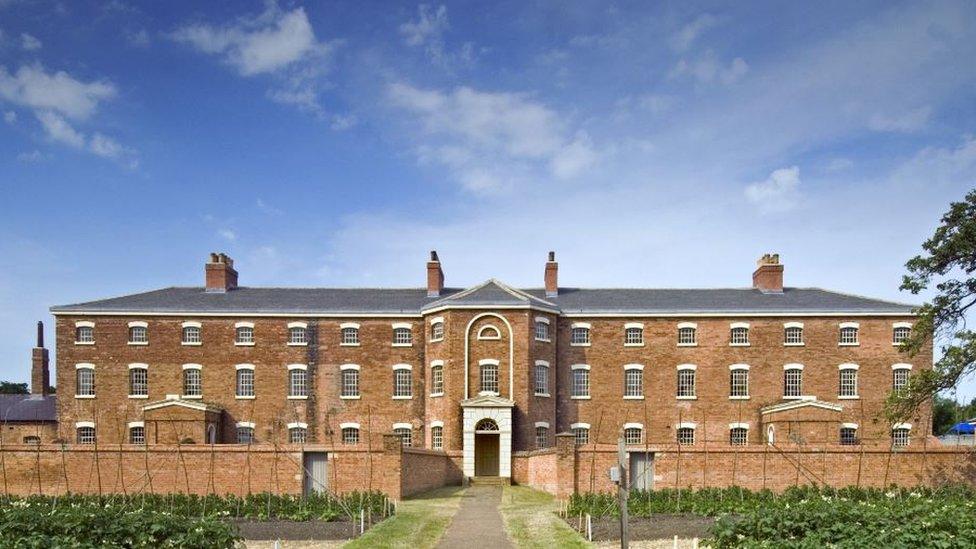

The sprawling, factory-like building to which Susan and her family had been brought was a Victorian workhouse - one of the first to be built in the country. The workhouses' harsh regimes, which involved subjecting the "idle and profligate" to hard, monotonous tasks such as rock-breaking, would become notorious.

But the shocking thing about Susan's case was that she and her family were not born in the times of Charles Dickens. Their life at Southwell's workhouse, in Nottinghamshire, began in 1968 and lasted until 1971.

"I used to spend hours with my little doll, looking out of those windows, thinking, 'When is somebody going to come and take us away?'"

Pauper's path

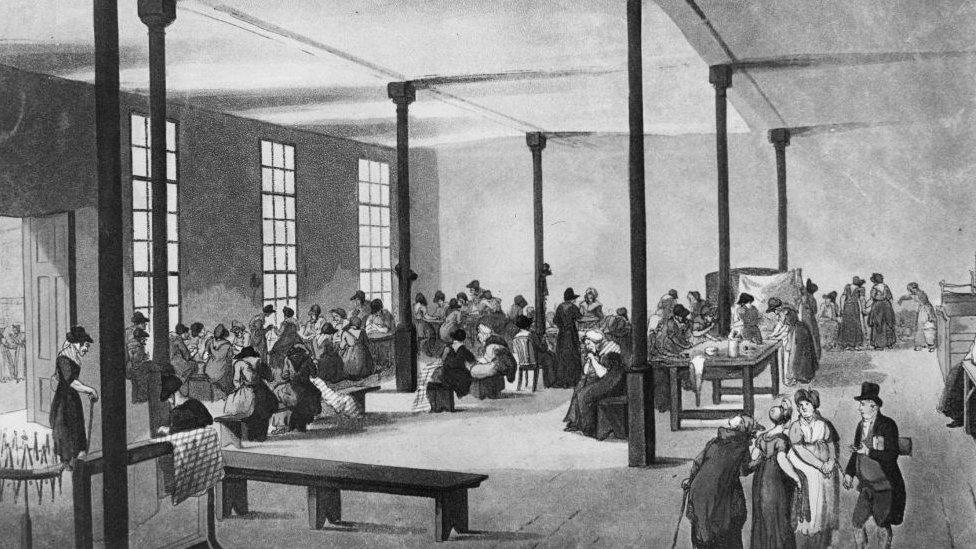

The workhouse system had many prominent critics, including the author Charles Dickens

Southwell's workhouse was built in 1824 by the Rev John Beecher, with its architecture influenced by prison design. It was one of the first examples of a notoriously harsh regime, which was adopted nationally in 1834, to force vulnerable people to work in exchange for accommodation and food.

The workhouse was home to 158 inhabitants - men, women and children - who were split up and forbidden from meeting. Those judged too infirm to work were called the "blameless" and received better treatment but the rest were forced into tedious, repetitive work such as rock breaking or rope picking.

In 1948, a new welfare system saw the end of Southwell's function as a workhouse and it was used as temporary homeless accommodation until 1976. However, the National Trust, which now owns the site, says some social historians view such shelters as similar to workhouses.

At first, the workhouse provided a kind of sanctuary for Susan and her siblings.

Until then their existence had been precarious, shuffled from place to place as their dad, Brian, moved in and out of prison.

At school Susan (first on the left) was stigmatised because of where she lived

For a while the family lived in a derelict Victorian terrace in Newark, but then Brian moved in with his girlfriend, leaving his family on the street.

"My mum traipsed around to the bus station and we sat there for four hours," Susan remembers. "Eventually, the bus inspector asked us what we were doing and my mum said, 'We've nowhere else to go'. So we spent the night with the Salvation Army."

Coming to the workhouse was, at first, a relief for Susan but steadily the cramped confines wore her down

The next day, the family were taken to Southwell Workhouse - known at the time as Greet House.

In the 20th Century, workhouses became known as public assistance institutions and were intended to provide temporary accommodation for homeless people, but the stigma associated with the regime endured.

"It was a relief at first," Susan says. "My dad wasn't always belting us. He wasn't shouting and screaming at my mum."

Susan has memories of building a den in the high hedges with her brother and endless hours of reading library books.

Susan describes her mother, Joan, as "a good mum" but the workhouse life meant she "gave up"

But gradually, the institution began to grind the family down.

"The rules of the place seemed as if they had come from Victorian times," Susan recalls. "We weren't allowed to mix with anybody.

"My dad was back in prison again but it felt as if we had been sent to prison too."

Her school attendance was sporadic but, when she did go, she remembers the other children calling her a "Gypsy".

"Anybody could have come in and walked up those stairs," says Susan

"We were stigmatised because we lived at the workhouse," she says.

The long, echoing rooms were frightening for a child, particularly at night.

"There were no lights and the bit we lived in was completely open - anybody could have come in and walked up those stairs," says Susan.

"There was a shared corridor that ran down to the toilet and I hated going there, especially at night. I used to imagine people coming up the stairs to get us."

The whole family had to share one small room

And living on top of each other, in one small room, took its toll.

"To live in one room for so long with so many people, you just lost all of your privacy," said Susan.

"My mum gave up. She didn't care if she lived or died. She would either sit there being quiet, or cry."

With her mother, Joan, increasingly dependent on alcohol and sleeping pills, it was left to Susan to care for the family.

Each week, she used the family's social security money to buy food and a bottle of sherry for her mum, and to pay the rent to the wardens.

She also had to go to the doctor to get her mother's sleeping pills.

"It was traumatic having to do that," she says. "I was sitting in the waiting room with a begging letter from my mother and everyone knew who I was and why I was there.

"If my mother didn't get her drink or tablets, she would be in a temper. She was a really nice mum but she had been through so much.

"We got to the point where we would do without food so she could have her sherry."

It was Susan who did most of the family's cooking - tinned food, mainly - and cleaned the room, which was inspected each week.

"You had to make sure it was clean at all times - that was one of the rules," she says.

There were few toys, while second-hand clothes and shoes were provided by a charity.

Susan was left to take responsibility for her family, as her mother's health deteriorated

"None of the shoes ever fitted properly and I didn't know what it was like to get a haircut," Susan says.

The other families at the hostel moved on after a few weeks but Susan's family were repeatedly overlooked.

"They just wouldn't give us a council house," she says.

The overall feeling was one of having been forgotten.

"We were just left to ourselves," she says. "That's what I feel so angry about now. Why did it take three years to move us out of the workhouse?"

A small courtyard was the only outside space for the workhouse's 20th Century residents

Finally, the family were provided with a council house in Southwell and left the workhouse.

A few months after they left, the building stopped being homeless accommodation and was instead used by social services and for elderly care. Sections of it became derelict.

In 1997 the former workhouse was bought by the National Trust, which restored it. Staff and volunteers dress up as Victorians and tell visitors of the building's past life.

Tourists can learn about workhouse life by taking a tour of the premises

Among the volunteers is Susan.

"People say they are surprised I want to go back there," she said. "But I am glad people want to listen to me, because nobody wanted to listen to me at the time.

"It's important the story of the workhouse is told. When I see people lying in shop doorways, I think, 'What is your story and will anybody ever want to listen to it?'"

The room where Susan lived has been redecorated as a near-replica of what it looked like when she was there.

She says visitors are shocked when they happen upon the relatively modern furnishings amid the Victorian costumes and settings of the rest of the workhouse.

"Sometimes I think people reckon I'm in cloud cuckoo land, saying I lived here," she said.

"I have a lot of anger in me for the neglect we suffered from social services and the professionals who saw what was happening to us and did nothing to help us.

"But my volunteer work helps me deal with the anger in me."

You may also be interested in:

Susan now volunteers at the building, which is owned by the National Trust

In later years, Susan drifted apart from her siblings. Age 60, she is married with grown-up children and has just retired from her work as a shop manager.

"I felt so, so lonely the whole time we lived there. When you live in a place like that, with no neighbours, no friends, you really know what isolation feels like. It's a really deep-down thing that will always be with me."

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, or on Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk, external.