Broadside Ballads reprinted by Oxford Story Museum

- Published

.jpg)

The Bodleian Library has more than 30,000 compositions in its collections

Imagine receiving your daily dose of current affairs from a drinking song.

Sold on street corners for a penny, Broadside Ballads contained stories of scandal, social commentary and propaganda and were performed in taverns, fairs and homes far and wide.

"The ballad sheets were the tabloids of their day, whether it was celebrity scandals, sporting triumphs, shipwrecks, murders or bizarre deaths," folk musician Tim Healey says.

Children's author Michael Rosen, whose hobby is tracking down the compositions, calls them "literature of the people".

The Story Museum in Oxford is reprinting the songsheets using the equipment that made them ubiquitous.

It ties in with a new display at the Bodleian Library called Illustrations of Early Printed Ballads.

Printer Paul Nash said: "The idea was to produce a modern version by traditional means."

'Lascivious gestures'

The Oxford library has more than 30,000 compositions in its collections.

These Broadside Ballads - named after the side of a ship because they were printed on one side of paper - provided entertainment for the masses and were the cheapest form of print.

Mr Nash said: "Although it is a painstaking process, the skills of printers, compositors and pressmen meant they could have a ballad out by the end of the day."

Dr Alexandra Franklin, project co-ordinator for the Centre for the Study of the Book at the Bodleian Library, said: "The ballad singers would sing them on the street to get attention so they could sell them.

"If it was a little risqué or there was innuendo, some ballad singers could be accused of using lascivious gestures to accompany their singing in order to make explicit what the song was about."

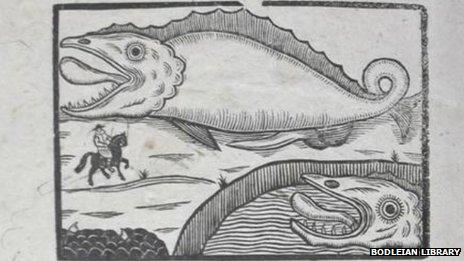

A beached whale in the 17th Century became the subject of a song

Some cover one-off events, such as a description of a "strange (and miraculous) fish", which depicts a day in 1635 when a whale was beached in Cheshire.

In this case the balladeer can only make sense of the "monstrous" creature by describing it as a "herring-hag", and "rare / Beyond compare / In England nere [never] the like".

As was the tradition, it is accompanied by illustrations printed from engravings in blocks of wood, resulting in comic-strip style panels.

Tim Healey performs Broadside Ballads with his band The Oxford Waits.

He said: "Anything weird, like a great big whale being washed up on a beach, you would have found in a ballad sheet."

Other ballads offered escapism from a humdrum existence.

The honour of a London prentice told a dramatic account of an apprentice sent on a business trip to Turkey.

He ends up killing two lions with his bare hands.

.jpg)

The honour of a London prentice depicted the hero performing brave deeds

The London Damsel's fate, by unjust tyranny, tells of a girl who is forced to marry a man against her will, despite having met her true love.

And as well as matters of the heart were matters of state.

The conclusion of the English Civil War was depicted in Win at first, lose at last; or, a new game at cards, "wherein the King recovered his crown, and Traitors lost their heads".

While the ballads are evocative of their time, they are not, in most cases, great art.

Mr Healey said: "You can still find a body of ballads that are beautifully written about eternal themes that can still make you laugh or make you cry.

"It's like panning for gold... a lot of it is dross but there are nuggets."

Dr Franklin admitted the compositions were written by "hacks".

She added: "It was mainly a production line.

"But there are some wonderful lines in the ballads which, if you like very simple poetry, are very effective."

Paul Nash (left) has reprinted the ballads using traditional methods

Mr Rosen cites The Flying Cloud, an account by a sailor forced to work on a slave ship, as "artistic documentary".

He said: "Here's somebody who is a white man, describing being a seaman on one of these slave ships.

"It's an insight into a working life at a painful and terrible moment in history."

For Paul Nash, after printing 500 sheets on a press made in 1669, it was time to sell the ballads to a new generation.

Instead of the traditional penny price he opted for a pound.

"I tried to sell them in the street but I wasn't terribly successful… people aren't used to it today and they thought I was mad."

But Dr Franklin thinks the Broadside Ballad lives on in other ways.

"They're significant to us today when we think about what we like to read in newspapers or online.

"Unfortunately we do still have an appetite for scandal and other people's misfortune, so the category of writing that the ballads represent has not died away at all."

- Published21 November 2012

- Published18 November 2012

- Published8 November 2012