Fizzing or flat: A tale of two Somerset cider mills

- Published

Somerset now has over 60 small cider-makers producing relatively small quantities

The cider-makers who gave the world Blackthorn and Babycham are to shut down after more than 200 years in production.

But while the mill in Shepton Mallet, Somerset faces closure, another cider mill, just 20 miles up the road is busy installing new cider tanks worth more than £3m.

So why is one cider-maker sparkling with success, whilst another is scraping the barrel for survival? Their fortunes reveal not just what's changing in cider, but in tastes and fashions.

The difference is ownership - the first is owned by multinational Dublin-based C&C Group and the second by family firm Thatchers.

The cider mill in Shepton Mallet is owned by the Irish cider firm, C&C Group

Union leaders insist the C&C plant in Shepton Mallet is profitable and criticised the decision to relocate to Ireland. Steve Preddy, from Unite, said the mill made 17m euros (£13m) last year.

He said: "It is quite clear the workers are being sacrificed to generate cash for the company."

Shepton's mill is one of C&C's three plants working, I am told, at just 34% capacity - so like any sensible business, it has shut two.

The survivor just happens to be located in Clonmel, County Tipperary, where C&C was born.

Cider, the firm claims, has got tough. It said in a statement: "The trading environment in the UK and Ireland has been intensely competitive over recent years."

Alan Stone runs the cider competitions at the Bath and West agricultural show

But cider insiders see a deeper story. Alan Stone, who has written several books, runs the cider competitions at the Bath & West Show and is vice-chairman of the Shepton Mallet Chamber of Commerce.

He said: "It is quite clear that C&C ran down the marketing operation behind Blackthorn and Olde English, hoping people would switch to Magners, the firm's Irish brand.

"But in the West Country, people just moved to Thatchers and the new craft ciders instead."

And drive just 20 miles to the small North Somerset village of Sandford and you see what Mr Stone means.

It's called Myrtle Farm - a farmhouse surrounded by orchards. But Martin Thatcher's grandfather would not recognise the enormous steel-framed buildings that house the kegging plant, the dozens of articulated lorries constantly loading in the yard, or the latest addition: shiny new tanks.

Martin Thatcher has just installed 18 new stainless steel cider tanks

Mr Thatcher is the fourth generation in his family to make cider, and he is very proud of his new tanks. Stainless steel, about 50ft (15m) high, each holding 250,000 litres of cider at precise temperatures. There are 18 of them, with space in the new building for another 36. The total investment is over £3.5m.

"We now make as much cider in a day as we did in a year when I first joined the business 25 years ago," Mr Thatcher said.

Mr Thatcher is the fourth generation in his family to make cider

Last year Thatchers sold over 100 million pints (57 million litres), up 10%. But, he insisted, the process had not fundamentally changed.

"We make cider just the same way as my grandfather did. We use Somerset apples: my favourite is the Somerset Redstreak, which we juice and then ferment. No concentrates, no added sugar, just juice."

Thatchers is very careful with this process. The company have seen what the market likes, and it is a traditional story. Last year the firm planted 50,000 apple trees. It all seems very laudable. But it is also where the money is.

Ten years ago cider began to boom. If you thought cider was a cheap, rustic drink offering lots of alcohol and a bad hangover, you were re-educated by saturation advertising. Orchards, apples, cold golden nectar on hot summer days.

It worked. Sales rose by 24% between 2006 and 2011. But it also changed the market. Today, the supermarkets want more premium, artisan ciders, and only a few mass-produced brands at knock-down prices. Tesco now stocks 60% more varieties than it did in 2001.

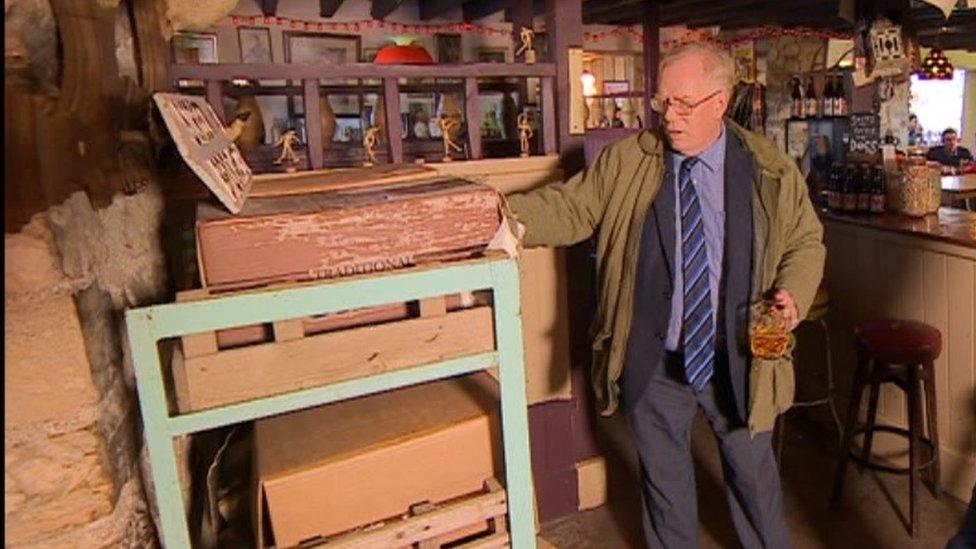

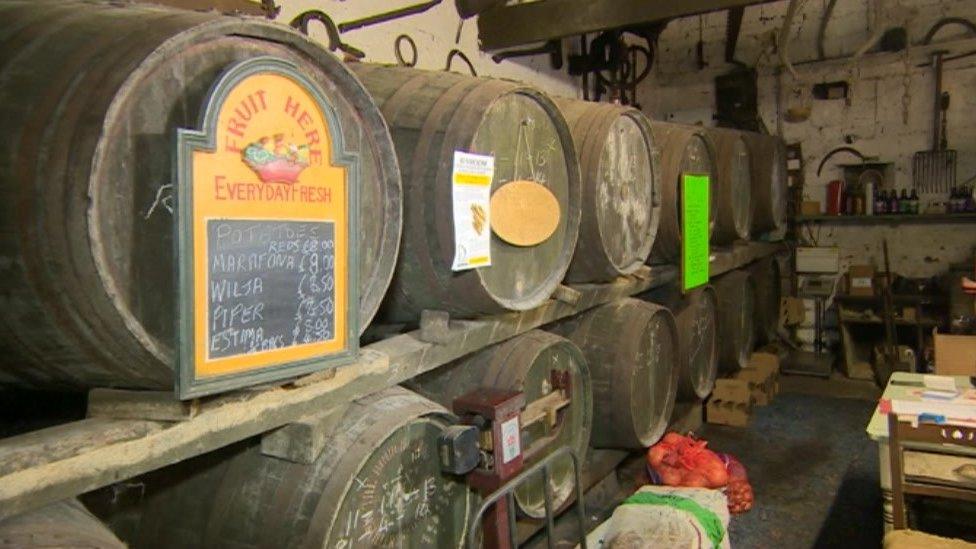

Neil Worley makes Worley's Cider almost single-handedly in a rented barn near Shepton Mallet

Today Somerset has over 60 small cider-makers, producing relatively small quantities of distinctive cider, usually in eye-catching bottles.

Some go back generations, like the Hecks family from Street, who have been at it for 175 years. Others are new arrivals, like Neil Worley who makes cider almost single-handed in half-timbered barns he rents just outside Shepton Mallet.

Mr Worley said: "We're part of a change in how people like their food and drink. Everyone wants to know where stuff comes from, how it's made. I don't really think you can become the size of an enormous cider maker and still make cider the way we make it, it's not physically possible."

- Published12 January 2016

- Published15 November 2015

- Published20 May 2014