Powered by poo: Somerset dairy farm enjoys biogas boom

- Published

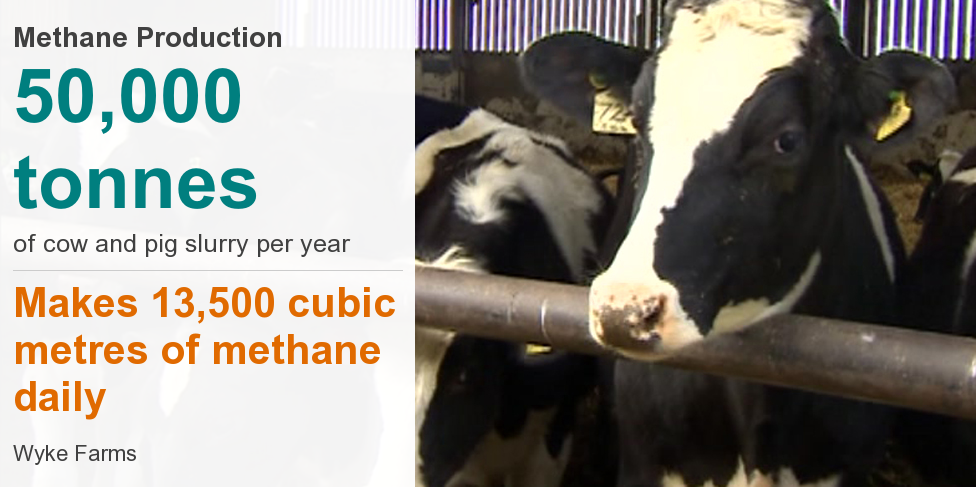

Wyke Farm has three anaerobic digesters which extract methane from animal waste

A dairy farm which converts manure into methane gas has increased production so fast it is now making enough gas for 6,000 homes.

So-called biogas has become controversial in recent years, with claims that land is being turned over to fuel production rather than food.

But dairy farmer Richard Clothier insists there is huge untapped potential in natural waste.

"For us, the muck is now as important as the milk," Mr Clothier said.

He is the third generation of his family to farm dairy cattle near Bruton, in Somerset. His firm, Wyke Farms, has grown to be one of the UK's largest independent cheese makers.

Richard Clothier said a "huge energy bill" inspired him to take control of the farm's energy needs

When you visit a dairy farm, they usually show you fine young cattle and perhaps a fancy new milking parlour. Mr Clothier starts his tour with the slurry tank. A large, steaming, swirling pool of brown cow muck and water. He loves it.

He said: "We bring school children here and they love the fact that we make power out of poo. They never grow tired of saying it, and nor do I."

Methane gas is produced inside sealed tanks by millions of bacteria and then filtered and cleaned

Next to the slurry tank, three huge green domes the size of a circus big top rise from his Somerset pastures. Stainless steel pipes emerge from the top of each dome, feeding small industrial buildings. Everywhere you go there are doors with official hazard signs, much as you would expect in a power station.

And that is exactly what this farm has become. A power station. The methane gas produced inside the sealed tanks by millions of bacteria is collected, filtered and cleaned.

Once it has reached the standard of the national gas grid, it has the regulated odorant added to it, the familiar safety smell you get if you leave the gas on at home.

The final shed is the one the farmer is most proud of.

"This is where we connect to the grid," he said.

There are dials, pressure gauges, yellow pipes. And a gas meter that spins quickly.

"Here we are pumping 13,500 cubic metres every day, that's the pipe that goes down to Bruton. All their gas comes from us now, it must be the greenest town in Britain."

In fact, the farm feeds much more than just the nearby village - Bruton has a population of about 3,000. Mr Clothier's dairy gas works is producing enough for 6,000 households.

Most do not realise their gas comes from a dairy farm, it is exactly the same as any other gas on the National Grid. So could more farms follow suit?

For Mr Clothier, the light bulb moment was a huge energy bill a few years back. Oil was more than $100 a barrel and one month the dairy's power jumped £70,000.

He said: "There's obviously no way you can go to the supermarkets and tell them the cheese will cost more, they just won't be interested."

So he and his family sat round the table and decided they needed to take control of their energy.

Some of the gas is now used on the farm to power a generator building, producing around 500 kWh of electricity to run the cheese making process. They also recover water from the whey, allowing the entire operation to run self-sufficiently.

But the system is not cheap, in total they spent £14m. Clearly not every dairy farm could raise that but Mr Clothier insists more anaerobic digesters should be built.

He said: "On farms around Britain there's an untapped potential of organic waste.

"Some domestic houses are not collecting food waste yet, so there's so much organic waste out there that can be used to generate gas and electricity."

Wyke Farm uses biogas to generate all the electricity needed to make its cheese

Others have raised concerns about the growth of anaerobic digesters. Mr Clothier's plant runs on waste, but others are fed with crops grown for fuel, especially maize.

This has led to large parts of the UK being cultivated for fuel crops. Worse, maize is often grown in a way that increases soil erosion, accelerates the run-off from rainfall and exacerbates flooding.

Environmental journalist George Monbiot believes the original aims of anaerobic digesters have now been corrupted. "There could scarcely be a better formula for subverting everything biogas is supposed to achieve," he claimed.

Back in Somerset, Mr Clothier has read all the controversy. He insists he is only going to feed his gas tanks with waste.

"My grandfather always used to say 'be good to nature, and nature will be good to you'. We're here to make cheese, and if we can make power out of what was once waste, that's great. And there is plenty of muck to go round."

- Published21 August 2014

- Published6 August 2013

- Published4 March 2011