Bill Tutte: The unsung codebreaking hero of World War Two

- Published

Bill Tutte was invited to help with the codebreaking efforts at Bletchley Park in 1941

He managed to decipher a secret Nazi code without seeing the machine responsible and is thought of by many as a hero, but Bill Tutte is by no means a household name. As a memorial is unveiled in his honour, BBC news looks at the man credited with shortening World War Two.

Richard Youlden says it was never much fun playing the board game Mastermind with his great uncle, Bill Tutte.

A player is given about 10 goes at guessing their opponent's chosen combination of four coloured pegs.

With every guess, the person who set the pattern responds with how many colours were right, and how many were in the correct position.

"He would put down a few lines of colours, getting my responses," Mr Youlden, 54, said.

"He would then sit there and stare at it for a few minutes, smile and put down the right answer.

"On one occasion he put down his answers and I said 'no, that's wrong'.

"He said 'I think you've made a mistake'.

"I had."

The brilliant mind of Bill Tutte, bottom row, right, was spotted by Cheveley Village School's head teacher

Mr Youlden was a teenager at the time and at that point had no idea about the historical importance of his opponent, the very quiet, studious 'Uncle Bill'.

About 35 years earlier, in 1941, Britain was at war and Bill Tutte had been invited to help with the codebreaking efforts at Bletchley Park.

Tutte was born in Newmarket, Suffolk, in 1917 and from an early age had demonstrated a phenomenal grasp of mathematics.

He came from a humble background but was offered scholarships at a high school in Cambridge and later at the University of Cambridge.

A local charity is said to have bought him a bike to help him get to Cambridge.

"He was a very gifted mathematician at Cambridge," said Kevin Murrell, from the National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park.

"Lots of these mathematicians were rounded up and recruited into cryptanalysis and cryptographic work at Bletchley Park, decoding messages that were sent by Hitler's high command."

At this time work was already being carried out by Alan Turing and his colleagues on decoding messages sent via the Enigma machines.

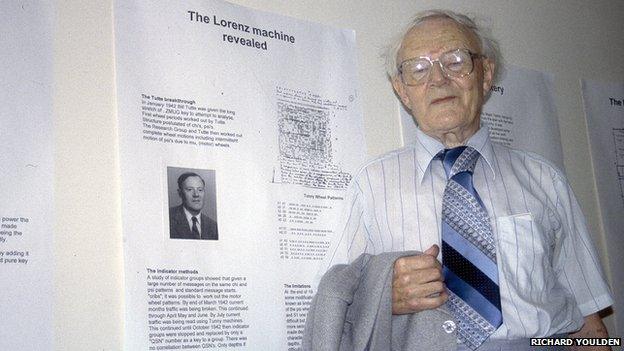

Richard Youlden visited Bletchley Park with his great uncle in the 1990s

But there was evidence of another system being used by the Nazis to send secret messages.

"It was called the Lorenz system and was several degrees more advanced than Enigma," Mr Murrell said.

Tutte was presented with the task of deciphering the teleprinter code.

It took him about six months.

"What Bill was able to do, with just a couple of captured messages, was to sit down and work out what this machine in Berlin would have been doing," Mr Murrell said.

"This was without ever seeing the machine, or reading anything about it.

"That's probably the single biggest intellectual achievement at Bletchley during World War Two."

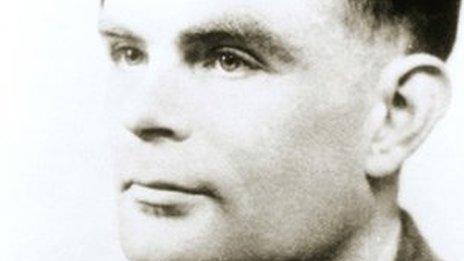

Bletchley Park housed codebreakers including Alan Turing, famed for breaking the Enigma codes

Based on Tutte's findings, the engineers at Bletchley were able to construct a device which mimicked the German encryption machine.

"Once Bill worked out how the Lorenz cipher machine worked it was possible to, by hand, decrypt the messages, but it was taking a good six weeks," Mr Murrell said.

"By the time you've decrypted a message that is six weeks old, it's all rather too late."

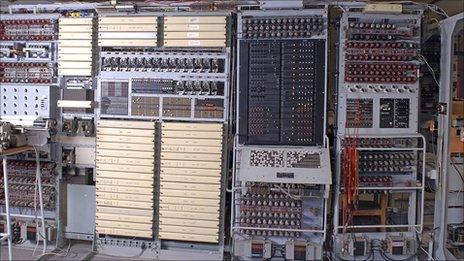

The desire to speed up the process led to the development of the "first pre-computers", including Colossus.

"Colossus operates on the techniques Bill developed," Mr Murrell said.

"It cut the six weeks decrypt time down to about six hours, which is quite phenomenal."

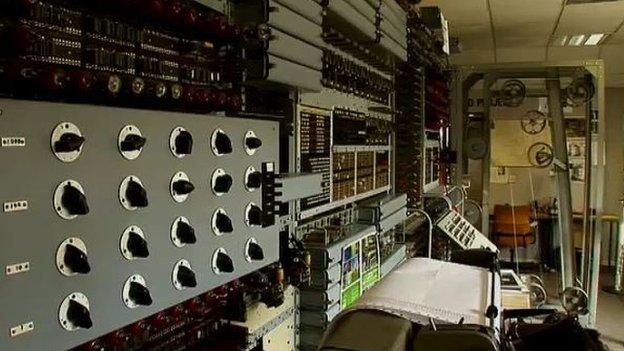

A reconstruction of the British Tunny machine, used to decode the Lorenz cipher, can be seen at Bletchley

Bill Tutte married but did not have any children

Towards the end of the war, the Allies were leaking false information to the Germans about when attacks would be made.

"It was important to understand whether that leaked information got to the Germans and whether they believed it," Mr Murrell said.

"It's because we understood how that coding system worked that we understood that Hitler had fallen for that misinformation.

"That was vital for D-Day."

Like the rest of the world, Richard Youlden learned about his great uncle's achievements in the mid 1990s.

"Obviously I didn't know how involved he'd been in codebreaking, but it became very clear why he was so good at Mastermind," he said.

"I was very surprised and impressed.

"What he managed to do changed everything."

Tutte died in Canada in 2002, just a few years after details of the secret operations at Bletchley had started to be released.

"I think he managed to say a lot of the things he wanted to say, and explain the main part of what he did," Mr Youlden said.

"But there were things he could never tell us."

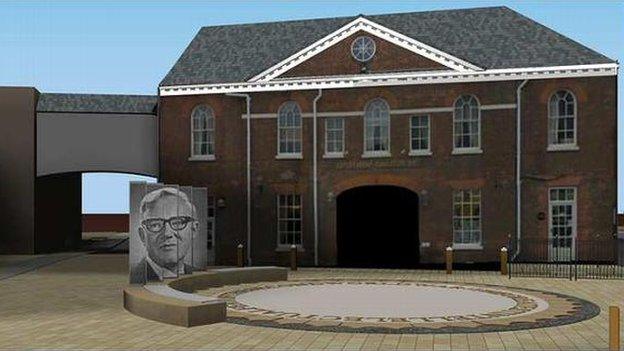

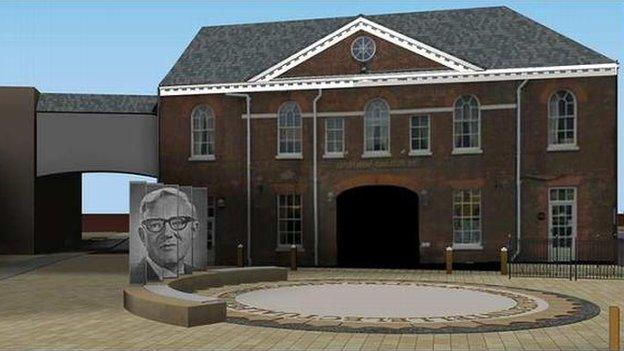

An artist's impression of the memorial for Bill Tutte, to be unveiled on Rutland Hill, Newmarket

The original Colossus was destroyed after the war

In Newmarket, a memorial is being unveiled to celebrate Tutte's work.

Campaigners hoping to raise awareness of his achievements will also launch a scholarship scheme, with the aim of giving other people from a similar background to Tutte the "best education possible".

David Cameron wrote to Tutte's family in 2012 to acknowledge his work, but Mr Youlden said more could be done.

"I'd like to see a lot more attention given to the other people at Bletchley, not just Bill, as they made such a big contribution," he said.

"The map people, the radar people, and all the others - they're still hidden in the background to a large extent.

"There are a lot of stories out there still to be told."

- Published18 June 2014

- Published5 July 2014

- Published8 June 2014

- Published6 February 2014

- Published18 June 2014

- Published8 February 2012

- Published22 June 2012

- Published24 June 2012