Remembrance Sunday: Holocaust survivor shares why it is important

- Published

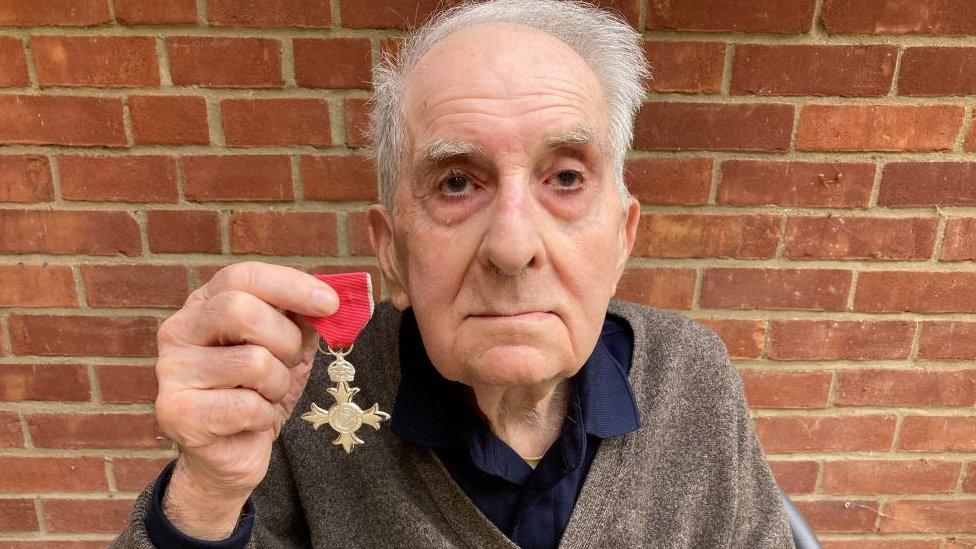

Frank Bright was appointed MBE as part of Queen Elizabeth II's last New Year's Honours earlier this year

Frank Bright MBE was 16 years old when he was spared the gas chambers in the Nazi death camp of Auschwitz, but his mother and father did not survive. Now 94, Mr Bright says his life has been shaped by their murders and, as the UK marks Remembrance Day, it is important to "never forget" lives lost in World War Two.

"I realised I was on my own and I wasn't prepared for that. I always depended on my parents," says Mr Bright, who moved to England after the 1939-45 conflict and lives in Suffolk.

His parents Hermann and Toni Brichta were among an estimated 1.1 million people killed at Auschwitz in Nazi-occupied Poland.

The Jewish family had fled from Nazi Germany to Czechoslovakia in 1938, but after Hitler's forces annexed that country, they were subjected to restrictions in Prague, imprisoned in the Theresienstadt ghetto, external and eventually transported to Poland.

He says he can still remember the "stench of death" of Auschwitz, where he arrived on 12 October 1944.

Frank Bright (second from right) was born in Berlin as the only child of Toni (furthest right) and her husband Hermann (not pictured)

Mr Bright, who was born Frank Brichta in Berlin in 1928, says his father had been sent to Auschwitz and "disappeared" two weeks before he was sent there with his mother.

He says when they arrived, they were separated into lines of those who had been "declared fit for work" and those who were to be sent to their deaths as part of the genocide of Jews and other groups including gypsies and homosexuals.

"My mother spotted me, broke ranks, came over to me, shook hands with me and went back," says Mr Bright.

"I saw her go along this ramp and at the end of it, was turned left... and that was the last time I ever saw my mother."

He says the loss of his parents "hit me very hard".

"At first it didn't sink in," he says.

"An iron curtain came down in my mind, I just couldn't face it, and it took years and years for the curtain to lift and for me to realise what the situation was and I had to cope with it as best I could."

Frank Bright (circled) at a Jewish school in Prague during the occupation by Nazi Germany

Mr Bright, who was born was born Frank Brichta in Berlin in 1928, arrived at Auschwitz on 12 October 1944

Left with no parents and the loss of most of his childhood education, Mr Bright says he had to "make the best of a bad world".

"It upset my life completely losing my parents, it turned my life upside down," he says.

It was after seven months of slave labour, Mr Bright was liberated in May 1945 when Soviet troops pressed west through Poland and the Germans retreated.

After making his way back to Prague and into the care of the Red Cross, he eventually secured his passage to London where he was able to live with distant relatives, who he had only met once before.

Eventually he was able to build a life for himself, taking evening classes to train as a civil engineer and working in Canada before returning to the UK to work with local authorities, including Suffolk County Council.

With his English wife, Cynthia, with whom he had two daughters, who are now both in their 60s, he settled in Martlesham Heath, near Ipswich, 35 years ago, where he still lives.

Cynthia, who was the same age as him, died last November, just weeks before her husband was named in the Queen's final New Year's Honours list.

He was appointed MBE in recognition of the work he has done teaching schoolchildren about the Holocaust - something he still does today.

Frank Bright settled near Ipswich 35 years ago

Mr Bright says making future generations aware of the events of World War Two and the Holocaust is "so important".

"If they don't know, then their children won't know, and their children's children won't know, and that does mean we do forget and we should not, we should remember," he says.

Mr Bright normally marks Remembrance Day with fellow members of the Martlesham Heath Aviation Society, external, who run a museum that commemorates the former RAF base east of Ipswich, which is now an industrial estate and housing.

However, his plans this year have been affected by a recent fall and he said he was unlikely to be able to attend any ceremony this year.

Nevertheless, he says he will be remembering not only his experience during World War Two, but all the lives lost and "sacrifices people made and had to make".

He says he came to Britain because of his distant relatives and because "Britain was seen as a safe haven by Jews... the fact that Britain was standing alone until the US entered the war at the end of 1941 was the only thing that gave us hope for a long time".

"There are so many things to remember," he says. "The whole of the people who were involved, I was only part of it and there were six million people of our race who perished and I try to remember them too because they are quite close to my heart.

"To forget them would be a disaster."

Ahead of the 80th anniversary of the end of World War Two, in 2025, the BBC is trying to gather as many first-hand accounts from surviving veterans as possible, to preserve them for future generations.

Working with a number of partners, including the Normandy Memorial Trust and the Royal British Legion, the BBC has already spoken to many men and women who served during the War - you can watch their testimonies here.

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published21 January

- Published10 October 2016

- Published26 January 2015

- Published14 April 2014